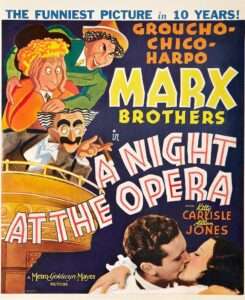

Opera Meets Film: The Marx Brothers & Verdi in ‘A Night at The Opera’

By John VandevertAlthough they are best known for films such as “The Cocoanuts” (1929), “At The Circus” (1939), and “A Night in Casablanca” (1949), one of the Marx brothers operatic-related films was just as spell-binding and deserves its place in history.

When “A Night At The Opera” first premiered in 1935 in the continental United States, the brothers were still under contract with the studio of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer for five films. In 1993, after becoming wildly successful, the film was added to the National Film Registry of The Library of Congress because of its historical and cultural significance. The cast featured many important cinematic and musical figures of the day, including Kitty Carlisle, Allan Jones, Margaret Dumont, Sig Ruman, and Walter Woolf King. Several of them had classical singing training, Kitty having studied with the world-famous soprano Estelle Liebling, while others like King studied as a baritone, although shifting the voice for the film. The “opera” element comes from the film’s usage of Guiseppe Verdi’s Il Trovatore and Ruggero Leoncavallo’s Pagliacci.

Entitled “A Night At The Opera,” the film marked the beginning of a new age of Marxian humor. The film also established the Marx M.O. when it came to comedic timing and the refinement of slapstick and class-based comedy based on establishing sympathy with the hero and animus for the villain.

Directed by Sam Wood and based on the eponymous short story by James Kevin McGuinness, the film’s script underwent several changes due to unhappiness with the quality. The brothers were additionally given a better identity throughout the process, the first script portraying them as unlikeable and aggressive rather than humorous. Despite the film’s historical relevancy, its box office beginnings were rather poor. The first viewing of the film didn’t go very well, it seemed, as the humor failed to translate to audiences. This was tested out in numerous theatres, but the results were all the same. However, after some editing to make sure the pacing matched the cadence of a typical stage production, audiences began responding much more favorably. Finally, the film began producing lucrative results, and its legacy was secured.

The Plot

The story revolves around three different main themes. Firstly, Mrs. Claypool, a widow who has been left a considerable amount of money, was supposed to meet her business advisor, Otis B. Driftwood, for dinner when she catches him with another woman. However, Driftwood soon introduces Claypool to Herman Gottlieb, director of the New York Opera Company. After a conversation or two, Driftwood convinces Claypool to contribute $200,000 dollars to the company, allowing, in turn, Gottlieb to hire one of the best tenors of their time, Italian singer Rodolfo Lassparri. The movie then focuses on Ricardo Baroni, who recently hired his best friend as his manager, Fiorello.

The movie’s central love triangle comes in at this point, as Ricardo has fallen in love with soprano Rosa Castaldi who, simultaneously, is being courted by the self-centered Lassparri. After the night’s operatic performance, the widow arrives backstage but sees the tenor attacking his dresser, Tomasso. The widow and Fiorello meet, although the widow unintentionally hires Ricardo thinking its the star tenor Lassparri. Flash forward, and many of the characters have departed for New York, although Ricardo, Fiorello, and Tomasso illegally come, too, stowing on board. They are eventually found out but, after showing resistance to leaving, are allowed to stay, being thrown into the ship’s brig (or prison). Upon landing, they eventually sneak away. Rosa and Ricardo embrace warmly upon their landing, but after getting into an altercation with the envious Lassparri, Rosa flees with Gottlieb. To get back at Lassparri for their capture, the three stowaways hijack an evening’s performance of Verdi’s “Il Trovatore,” eventually capturing the tenor and replacing him with Ricardo. The audience vehemently rejects the switch, and as Driftwood and Fiorello create a new contract, Rosa and Ricardo sing a much-enjoyed encore of “Miserere” to the hungry public. As they say, all according to plan.

The Opera in A Night at The Opera

The film samples various pieces from Verdi’s 1853 opera “Il Trovatore” and Ruggero Leoncavallo’s 1893 opera “Pagliacci,” although the former is far more central to the film’s narrative. From “Pagliacci,” the Act one soprano aria “Stridono lassù” (Screeching Upwards) is used. At this point in the opera, Nedda (wife of Canio, lover of Silvio) is afraid of her husband’s threat of retaliation for adultery between Silvio and Nedda. Finding comfort in the song of the birds, Nedda sings this aria, finding solace in the freedom the birds enjoy.

The selections used from “Il Trovatore” highlight the general direction and subtext of the film, the overture being used at the beginning of the hijacked production by the brothers, with a sample of the 1920s Tin Pan Alley song “Take Me Out to the Ballgame” thrown in for good fun. The “Gypsy Chorus” (colloquially Anvil Chorus) was also used. This piece can be heard in numerous other musical contexts, including Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Pirates of Penzance, although comically modified. Several other selections are used, including “Stride la Vampa” (Azucena’s Act two aria), “Di quella pira” (Manrico’s Act three aria), and the Act four duet “Miserere” between Manrico and Leonora.

Several of the singers were previously trained in the classical tradition, including Walter Woolf King, Kitty Carlisle, and Allan Jones. King’s true vocal identity was that of a baritone, making a name for himself in operetta and musical comedies. In 1919, he made his Broadway debut in the revue (a mashup of song, dance, and acting) “The Passing Show,” first created in 1894.

Carlisle’s singing training was with the excellent coloratura soprano Estelle Liebling, responsible for immortalizing many operatic cadenzas. However, her name is forever associated with her work as a vocal pedagogue, the internationally recognized soprano Beverly Sills having practically grown up with the teacher. A student of famed vocal pedagogue Mathilde Marchesi, Liebling’s work with Carlisle helped secure her voice well into her older age. A 1999 clip of her singing at the age of 89 is proof of Carlisle’s technical proficiency.

For Allan Jones, he had traveled to Paris for his vocal training shortly after becoming a seminal part of the American operetta and musical scenes. After establishing himself in these spaces, he quickly moved on to film, as his participation in this film demonstrates. For the purposes of the film, King had been dubbed by Hawaiian-born tenor Tandy MacKenzie, most known for his bel canto roles and interpretations of Puccini’s characters. He performed worldwide and made his operatic debut in the role of Rodolpho in Puccini’s “La Bohème” at the Théâtre of Cannes (now nonexistent) in 1929.

The Class Element

The film, much like the opera, shows how even class boundaries can be defined in times of classless struggle. In the film, the lower, middle, and upper-class positions are displayed in rather overt transparency.

Stuck in the lower class are opera chorister Ricardo Baroni, his friend Fiorello, and Tomasso, star tenor Rodolfo Lassparri’s backstage dresser. Although they both share some connection with operatic art, they can’t be considered in the world. Instead, they are outsiders and forced to fight for what they want every step of the way. Throughout the film, these three characters are portrayed as malignant, conniving individuals who undermine the morally and lawfully good social order in pursuing selfish desires. They stow away on business manager Otis B. Driftwood’s boat in an attempt to reach America. But even when they get here, their selfish antics continue undermining an operatic production of “Il Trovatore,” resulting in the celebration of Ricardo and soprano Rosa.

Occupying the middle ground is Mr. Driftwood, who is in the proximity of wealth but is not himself elite. His place in the power structure is hazy, as he doesn’t inherently belong to the upper class but also is not a member of the lower one. Instead, he unwillingly sits in the middle class, too rich to be considered poor but not rich enough to be considered wealthy. Thus, his character remains in a weirdly dissatisfied state throughout the film, helping the lower and upper class, and inadvertently sparks the central conflict of the entire film (accidentally signing Ricardo to a singing contract instead of the tenor Rudolpho Lassparri). One can only feel sorry for him, as he tries to be the good guy while always getting the wrong end of the stick, being fired by opera director Herman Gottlieb, although all are healed by the end.

Several people are seated at the top of the hierarchy, including Gottlieb, the widower Mrs. Claypool, and the tenor Lassparri. All the events happening below them and their social rank in this world are mere trifles that simply get in the way of their activities and decide which, throughout the film, they have to deal with unwillingly. In Gottlieb’s case, his role as the opera director puts him into direct contact with money, fame, and influence, evidenced by his working relationship with Lassparri and Claypool. On the boat to New York, Gottlieb is lawfully on board and is looking forward to having Lassparri sing at his theatre. He doesn’t realize that the lower classes are about to mess his production up, and this notion of the annoying and unconstrained lower class is put on vivid display. Claypool is also oblivious to the brothers’ antics, while Lassparri is directly affected by their meddling. However, Lassparri invokes his class consciousness in how he treats those around him, Rosa and Tomasso having to deal with less-than-ideal behavior. The fighting that occurs between Lassparri and the lower class shows that even if someone is upper class, the threat of being dragged down is always there.

Thank you to Cornell University Classical Studies department for the above observations.