Opera Meets Film: The Failure of Opera Crossover in Samuel Goldwyn’s ‘Thaïs’

By John VandevertThe now well-known story of a celibate, chaste monk (Athanaël) trying to convert a licentious courtesan and worshiper of the Goddess of Love (Thaïs), has decorated operatic stages and captivated audiences since its premiere on 1894 at the Opéra Garnier (National Opera House) in Paris, France. With a harrowing story originally written by the French writer Anatole France in 1890, being subsequently adapted and translated in a myriad of ways, the 10th opera of thoroughly Romanticized composer Jules Massenet has become a staple in the international operatic canon.

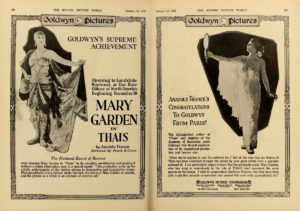

Yet, a part of the opera’s intricate history is a silent film from 1917 which, to this day, was and remains one of the biggest flops in American cinematographic history. The film itself was released on the 18th of December, 1917, the same day that Soviet Russia announced Finland’s independence!

Shot by the eminent and highly decorated American film director Samuel Goldwyn, with participation from American opera diva Mary Garden (she sang the role of Thaïs in the opera’s American premiere on November 25th, 1907 at the Manhattan Opera House) along with then-seminal actors Crauford Kent, and Charles Trowbridge, the film turned out to be a costly failure. Yet, from a historical point of view, it is a prime example of operatic cross-overs, and a cursed case of “great idea but bad execution.” Due to the low sound quality at the time, her exaggerated acting style by Mary made audiences laugh, an antithetical emotion to the sentiments of the story, and distracted from her speaking voice.

The filming took a total of ten weeks, with Mary’s salary reaching a staggering total of $150,000 dollars (in 2022, that’s an eye-watering 3.5 million dollars!). It’s interesting to note that Garden’s role in the film was only because, at the time, she was a well-established name in the American operatic world. Thus, if she was part of the picture, Goldwyn thought it his film was guaranteed to succeed. This didn’t end up being true, and in the end, the film didn’t read as well as it could have exclusively because of Garden. Currently, the film sits in three different archives across the continental United States, with no publicly accessible film recording available. It hasn’t seen the light of day since its premiere in 1917, yet given its massive failure, there is little hope that it will receive publicity anytime soon.

That same year, while Goldwyn was creating his “Thaïs,” across the water in Italy there was another version of the famous story being created as well.

This time, modeled after the highly popular Futurist movement, a combination of compelling imagery and on-screen dramatics, Italian Futurist cinematographer and photographer Anton Giulio Bragaglia created his cinematic film, “Thaïs.” It is considered the only Italian Futurist film to survive to the present. However, unlike Goldwyn’s film, the Italian version doesn’t stay faithful to the original story as written by French writer Anatole France. However, neither does Goldwyn’s film, as the film’s plot (staying true to France’s plot mostly) contains extra scenes where non-monk Paphnutius meets Thaïs. This doesn’t occur in France’s story, although acts as the rational prologue.

Mary Garden’s Cross-Overs

In her incredibly prolific career, Garden created the roles of seminal characters such as Marie in Lucien Lambert’s “La Marseillaise (1900),” Diane in Gabriel Pierne’s “La fille de Tabarin (1901),” and the title roles of Andre Messanger’s “Madame Chrysanthème (1901-1902),” and Jules Massenet’s “Manon (1884).” Yet, she is best known for being the creator of Claude Debussy’s Pelléas in “Pelléas et Mélisande (1902).” In a 1954 interview with (then) Assistant Manager of the MET Opera John Gutman, she remarked that Debussy was the only genius she’d ever worked alongside. However, it wouldn’t be until the second half of the 1910s that the film would come into her purview. In the late 1900s, after having sung at the Opéra-Comique almost religiously, she joined the Manhattan Opera House (1909-1940, now Manhattan Center), “Thaïs” being her in-house debut in 1907.

It’s seminal to point out that the eminent librettist and director Oscar Hammerstein had invited her to New York, whereupon she sang at Manhattan in the role of Thaïs (It was this succession of events that caused Goldwyn to find out about her and subsequently cast her in his film). Yet just a year later, she would go international again, singing at the Opéra National de Paris before returning to America to sing at the Chicago Grand Opera Company. By 1910, Garden’s name had become known nationwide, and while at the Chicago Grand seminal roles such as Fanny (Sapho), Dulcinea (Don Quichotte), Prince (Cendrillon), as well as premiering as the title role in American composer Victor Hubert’s opera Natoma (1911).

Once again, however, she left for newer waters, joining the Chicago Opera Association whereupon she sang in the titles roles such as Massenet’s Cleopatra and Henry Fevrier’s Gismonda (both in 1919). It was here that she’d dabble into the world of cinematography, befriending Samuel Goldwyn and subsequently starring in two of his films (Thaïs in 1917 and later The Splendid Sinner the year after). Archival pictures from that time show Sam (as he was affectionately nicknamed) alongside Garden in bouts of happiness, so one can assume the relationship between them was strong, despite the failure of the former.

From available sources, it doesn’t seem that Goldwyn had any type of relationship to Gardner before hiring her for his film, but according to the 1947 publication of LIFE Magazine, Garden didn’t respond well to the corrections given to her by Goldwyn, and thus the film’s end result was less than ideal. Yet, despite the tenuous relationship with the medium of film, she was again hired in 1918 for the film “The Splendid Sinner” in the role of Dolores Farqis, although the film is now considered lost. Although only two films, Mary Garden’s small journey in the cinematic arts is laudable, if not historical.

Samuel Goldwyn’s Flops

It’s easy to think that Thaïs (1917) was Goldwyn’s only failure of a “picture” (old-world speak for a film). This, sadly, isn’t the case. In the 1997 obituary of American lyric soprano Helen Jepson (1904-1997), best known as the first soprano to record the title role of Porgy in George Gershwin’s seminal opera “Porgy and Bess,” journalist Tom Vallance notes how in 1938 Goldwyn, in an extravagant bout of creativity, had imagined and created a production that brought together comedy, opera, ballet, jazz, and different kinds of popular music from composers of the day.

Titled, “The Goldwyn Follies,” this technicolor film (having only been around for about 20 years), it proved to be a failure like Thaïs, yet not because it was bad per se, but because it was far too busy, with a rather ambiguous storyline which was hard to follow among the undulating theatrics. In the film, Jepson can be heard singing arias from La Traviata (Brindisi and Sempre Libera) next to popular songs like “Love Walked In” (George Gershwin) and “La Serenata” (Enrico Tosselli). By 1978, it was considered a bad apple of a film, yet Goldwyn’s “failures” wouldn’t stop there. Earlier, when he was producing Thaïs, he had paid Anatole France himself $10,000 (in 2022, $231,383.59) for the rights to his story.

This conceivable set a bad precedent for the entire project, as the film was excessively expensive, with Garden being paid far too much which, on top of the cost of the picture itself, meant the film had racked up a huge bill. Outside of this film directly, Goldwyn had tried desperately to get authors of all kinds to Hollywood in order to produce their literary works into big-budget films, including the likes of anti-communist Rupert Hughes (best-known for “The Old Nest”, 1912) and suffragist Gertrude Atherton (best known for her “California Series”, 1902/1923).

Yet, the biggest name he’d try to impress was Irish playwright George B. Shaw (best-known for his 62 full-length plays and caustic opinions). When pressed about why the relationship didn’t work out he’s quoted as saying, “There’s only one difference between Mr. Goldwyn and myself. Whereas he is interested in art, I’m interested in money.” This seemed to be one of the leading motifs of his career, as in 1916 he created the company “Goldwyn Films” (which Thaïs was created within) with several partners, and after a successful merger with the “Famous Players Company,” although disputes would ultimately leave the company in his name. Thaïs apparently was the first (and last) picture under the company as in 1923, after a failed attempt to open sales offices overseas, “Goldwyn Films” became “Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer,” and he was soon kicked out of the trio.

He’d go independent for a while, and by the mid-20th century, he’d become a small, but highly respected, player in the world of Hollywood. Lauded for his publicity skills and autonomous tenacity, he became known as “one of the really great successes of Hollywood” in the words of colleague and film producer Darryl F. Zanuck. His 1943 film “The North Star,” a caustic film about the horrors of Soviet Russia’s role in WWII, was a box-office flop yet hugely important to him, and so it didn’t matter it was yet another flop in his career.

Despite the many obstacles over his career, Samuel Goldwyn’s contribution to the history of Hollywood and the cinematic artform was highly regarded during his time and his “Thaïs,” while lacking in drama, is part of that history too.

Categories

Opera Meets Film