Teatro dell’Opera di Roma 2025 Review: Lohengrin

By Ossama el Naggar(Photo: Fabrizio Sansoni)

Rome’s Teatro dell’Opera opened its season with “Lohengrin,” last heard at the Teatro Costanzi a half century ago, in 1975. Once Wagner’s most popular opera in this country, it fell out of favor with the new dogma of presenting operas in their original language. Between 1933 and 1966, it was performed on average every other season. Then it appeared once in 1975 under the baton of the legendary Giuseppe Patanè.

“Lohengrin” is back in the Italian capital, replete with “firsts.” For the first time ever in Rome, it’s presented in German. It returns in full force, under the baton of Italy’s talented conductor, and one who is most versed in the German repertoire, Michele Mariotti. It’s his initiation into Wagner. For Damiano Michieletto, Europe’s most talented opera director working today, it’s also his first foray into Wagner. Finally, the title role is sung by bel canto specialist Dmitri Korchak; his first entry into Wagner. A few months earlier, the versatile Russian tenor launched his conducting career with “L’italiana in Algeri” at the Rossini Opera Festival in Pesaro.

(Photo: Fabrizio Sansoni)

Production Details

This “Lohengrin” lived up to (and even exceeded) all expectations. Michieletto’s vision is, as usual, original and stimulating. As is his habit, he deconstructs a work and re-envisions it from its basic underlying ideas. The forbidden question of Lohengrin’s name is the foundation of the drama. Elsa is expected to blindly accept her champion who freed her from the accusation of having murdered her young brother. However, Elsa’s faith is weak and her fragility is expertly exploited by a malevolent Ortrud.

In this production, Michieletto makes generous use of symbolism. Silver, which represents purity, intuition, inner wisdom and self-awareness, is ubiquitous. Lohengrin’s battle with Telramund is not by sword, but by “Divine judgement.” An enormous stalactite drips molten silver on each of the contestants; he who withstands the pain is the winner. Telramund falters, and his arm catches fire, while Lohengrin valiantly undergoes the ordeal and even smears molten silver on his bare chest.

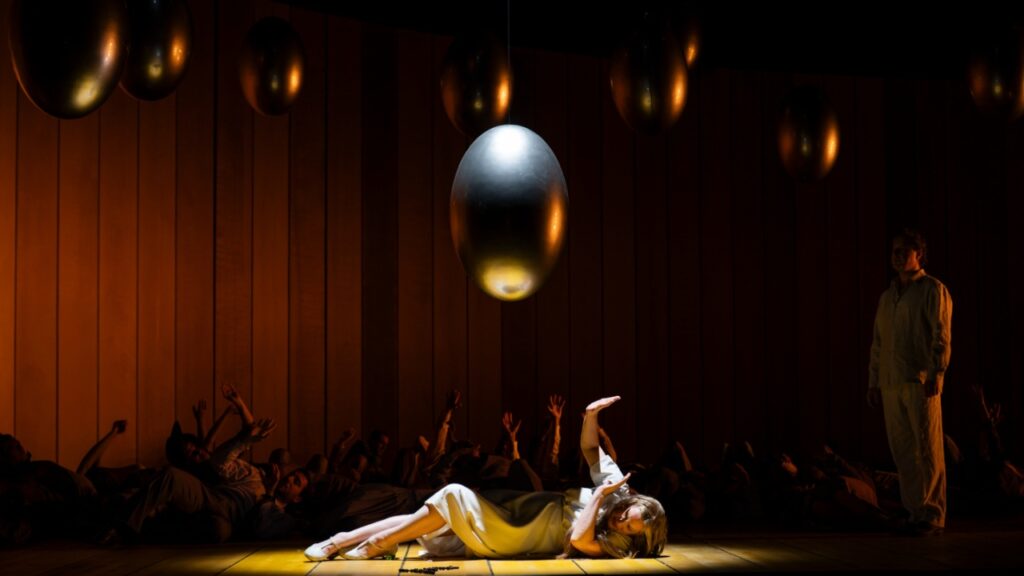

Another prominent symbol is the egg, representing new life, rebirth and transformation. It appears throughout, first as a mysterious object suspended from the sky. In Act two, it’s in a glass case beyond Otrud’s reach. Finally, when Elsa asks the forbidden question, the egg splits open, spewing toxic tar onto her as well as the chorus. Their eyes covered in tar signify their emotional blindness, as they were unable to believe in Lohengrin, the saviour knight.

The opera opens to Elsa removing a blue shirt and red shorts from a bathtub, representing the pond where her brother supposedly drowned. Elsa is distraught, appearing to be mentally unstable. Disheveled, she walks barefoot as if on an imaginary tightrope into the crowd, carrying her own dripping slippers and her brother’s clothes. When accused by Telramund of murdering her brother, her blank expression indicates bewilderment rather than denial. Initially, when no champion appears to defend her, she’s thrown into a pit, and black stones of coal are poured over her. Lohengrin appears, not carried by a swan, but carrying a child’s white coffin, with a silver swan insignia. He finds Elsa nearly disappeared into the black stone, gradually sinking deeper and deeper. This image, and that of Lohengrin retrieving her from the pit, are haunting ones that will remain engraved in memory.

Class structure and bloodlines are other elements that Michieletto emphasized. The conflict is two-fold; it’s between the old pagan faith and Christianity. It’s also between an ancient régime represented by Ortrud from the Frisian Radbod clan that once ruled Brabant, and King Henry the Fowler, the Saxon overlord of vassal Brabant. Faith among the people of Brabant is as weak as Elsa’s faith. The crowd is presented as weak, alternately submissive and fearful. The epoch is not defined, but the 1930s comes to mind and the location is either Nazi Germany or Stalinist Russia. At the opening, the Brabantians called “Grafen, Edle, Freie von Brabant!” They represent the bourgeoisie, the businessmen of the day in Brabant, eager to preserve their power. Ortrud is dressed elegantly in 1930s style. Her assured demeanour and condescending airs make her detestable at first sight. In Act three, when Ortrud erupts into the scene and humiliates Elsa, an indifferent crowd is scared of her. Again, Michieletto is stressing the passivity of the masses.

(Photo: Fabrizio Sansoni)

Musical Highlights

Vocally, the cast was almost as felicitous as the staging. Dmitri Korczak was an appealing lyrical Lohengrin, in the Italian tradition of the role: elegant singing and phrasing, no forced notes and a sweet seductive sound, especially in his arias “In fernem Land,” “Mein lieber Schwann,” and his Act three duet ”Das süsse Lied verhallt; wir sind.” The latter was no angry exchange, but rather tender reproaches. Korczak‘s

Heard a few months earlier as Sieglinde in Bayreuth, American soprano Jennifer Holloway has the ideal voice for Wagner’s lirico spinto roles, including Elsa. Endowed with bright, well-supported high notes as well as a strong middle and lower register, she used her vocal strength to nuance her interpretation. It’s hard to believe this magnificent soprano with a sweet timbre and brilliant upper register started as a mezzo. With her career mostly in Germany, her diction was the best of the cast. Michieletto’s view of the role is disturbing; Elsa is either a simpleton or a severely traumatized woman. Holloway portrays this tragic nature convincingly, and one can’t help but feel sorry for her. Only in her Act two confrontation with Ortrud does she show her backbone, a palpable moment both dramatically and vocally.

(Photo: Fabrizio Sansoni)

Russian mezzo Ekaterina Gubanova was a magnificent Brangäne and Kundry in the last Bayreuth Festival. Though here she portrayed a truly malevolent Ortrud, her voice was too light for the role. But thanks to her magnificent acting, she more than compensated. Rather than overwhelm Elsa and dominate Telramund with a powerful voice, this Ortrud used her awesome stage presence to intimidate.

Icelandic baritone Tómas Tómasson was a dramatically magnificent Telramund. He was able to convey the complex character of this anti-hero: ambitious yet weak, a sort of Macbeth, obeying his domineering wife, Ortrud. Though his baritone is not dark enough, he more than compensated, thanks to his powerful interpretation. Tómasson was one of the rare Telramunds one feels sorry for. Following his fall from grace after losing against Lohengrin, he perfectly conveyed his loss and incredulity. His black tailcoat suit was a pinnacle of elegance that starkly contrasted with his sorry condition following his defeat.

(Photo: Fabrizio Sansoni)

British bass Clive Bayley portrayed an exceedingly old King Heinrich. Unfortunately, his voice sounded tired, too much to sound imposing. In Michieletto’s staging, there’s an undercurrent of a critique of power, though it remains secondary. As with the aforementioned complicit noblemen in Act one, King Henry seemed more intent on keeping order than in upholding justice. Likewise, the Herald, excellently sung by Ukrainian baritone Andrei Bondarenko, convincingly portrayed an unquestioning bureaucrat.

As with most reinterpretations that diverge from the traditional telling, there are a few incoherencies that clashed with the libretto. If Telramund’s loss to Lohengrin was “Divine judgement,” Ortrud’s reproaches to Telarmund in their Act two duet made little sense. Moreover, Telramund’s suicide in Act three made Lohengrin’s justification to King Heinrich for killing the villain seem incongruous, to say the least.

(Photo: Fabrizio Sansoni)

Alessando Carletti’s imaginative lighting was essential to the success of this production. At the opening, semi-darkness conveyed Elsa’s disarray. Preceding Lohengrin’s appearance to champion Elsa, gradually increasing lights heralded a solemn and almost messianic event. At the end of Act two, the bright lights over Elsa in her wedding dress were stunning. Great dramatic effect was achieved by Carletti’s lighting in Act two’s scene between Elsa and Ortrud, as well as the confrontation between Ortrud and Telarmund.

Thanks to chorus master Ciro Visco, the Coro del Teatro dell’Opera di Roma shone. Though they don’t often sing in German, they managed to perform with decent diction. As for the Orchestra del Teatro dell’Opera di Roma, it produced a glorious sound, thanks to Michele Mariotti, the best Italian conductor of his generation. The masterful orchestrations of Wagner were in very capable hands, never obscuring the voices. Achingly beautiful wind, brass and string passages evoked strong emotional moments exactly when called for.

Until recently, the only Italian opera houses that could brag of their Wagner were Milan’s Teatro alla Scala and Bologna’s Teatro Comunale. With this production, Mariotti has established a landmark; Teatro dell’Opera di Roma has officially joined the fray.