Komische Oper Berlin 2025 Review: Jesus Christ Superstar

High-Octane Musical Production Illuminates Mass Media & Celebrity Cults

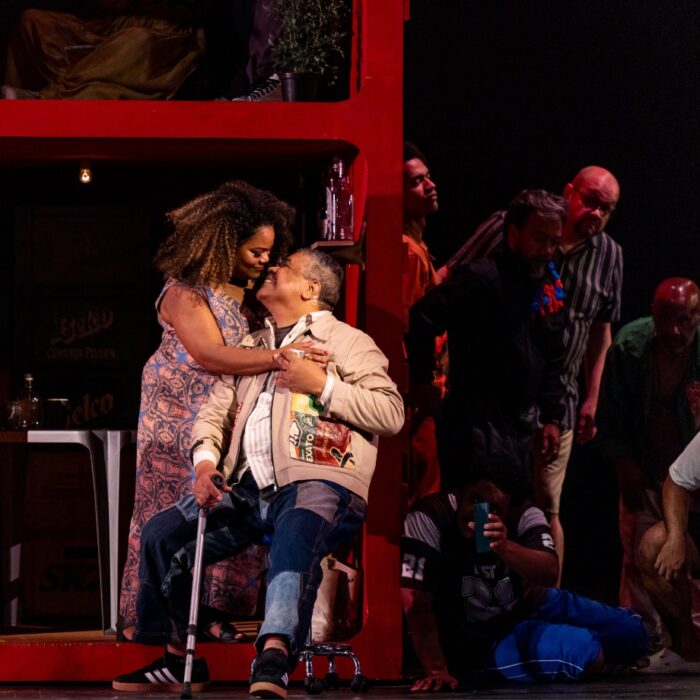

By Zenaida des Aubris(Photo: Jan Windszus Photography)

The Komische Oper Berlin’s colonization of Tempelhof Airport has by now hardened into ritual. Once again, Hangar 4 – cavernous, echoing with its aviation past – becomes a stage for the improbable. Tickets to “Jesus Christ Superstar” sold out so quickly, that two shows were added to meet the demand, proof that the company has mastered the art of turning outsized ambition into a box-office magnet. This season, alongside Mahler’s monumental “Symphony No. 8,” is Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice’s rock opera from 1971, that fills the hangar. At that time, it was one of the first works to be truly classified as a rock opera on Broadway, with Rice’s libretto recounting the last seven days in the life of a man who was admired and revered, then betrayed by his closest friend, and abandoned by the fickle crowd in a series of loosely connected scenes.

(Photo: Jan Windszus Photography)

Now, the ex-intendant of the Komische Oper, Andreas Homoki, along with his designer Philipp Stölzl, bring the show to life on a cat-walk like stage, dominated at the beginning and end by an oversize, glittering disco cross. For the protagonists, most of the action takes place on this catwalk, occasionally spilling out into the surrounding arena, mingling here with the 350 dancers, chorus and extras that form the writhing and swaying, nondescript, poor masses of humanity, giving their approval or disapproval of the action unfolding above them. Chorus master David Cavelius and choreographer Sommer Ulrickson’s masterful control over these forces trades subtlety for spectacle, seemingly whipping them into mass hysteria or subdued liturgy. Predictably, this energy is contagious to the audience being swept along, clapping and cheering. The drabness of the chorus and dancers only underlines the glitter-obsessed and fantastically colored costumes by Frank Wilde.

(Photo: Jan Windszus Photography)

At the center is the Jesus Christ of John Arthur Greene. A very athletic appearance in white, Greene – amplified, as are all singers – projects a flexible voice capable of lyric warmth and rock-edged power. He captures the paradox of a man adored and doomed, though dramatically he remains curiously aloof, blind to Mary Magdalene’s devotion, portrayed by Ilay Bal Arslan, who is bald and ascetic in a stylish Valentino-red long gown, and is the most endearing figure delivering the production’s most poignant singing: a Magdalene who laments with purity of tone, though her sorrow is staged almost too literally.

More convincing is Sasha di Capri as Judas, who plays him as an emotionally complex personality, who sets the tone in his first monologue with his grief and fear of losing the sheltered circle of friends that is the apostles. He sees the ideals of the group betrayed and wants to protect Jesus from himself, so to speak, by denouncing him. When he then caught up in the political machine and realizes the consequences of his actions he succumbs to madness and death.

Herodes, portrayed by Jörn-Felix Alt in wallowing purple robes, sees no reason to condemn Jesus to death, but ultimately gives in to the jeering crowd in exasperation, adequately expressed in an exalted tenorial state. Kevin(a) Walker as Pontius Pilates exudes comic authority as Herodes, especially as he delivers the 39 lashes with pyrotechnical bursts to the suffering Jesus. Oedo Kuipers is an innocent looking and lyric sounding Peter.

(Photo: Jan Windszus Photography)

Homoki’s dramaturgy impressively addresses the impact of celebrity cults and mass media. The crucifixion is not shown, only insinuated by the absolute kitsch colossal disco cross with its multicolored, blinking lights. More effective are the quieter tableaux: Magdalene cradling the dead Christ in unconsummated intimacy, or Judas receiving Christ’s forgiveness in a moment that gestures toward homoerotic undercurrents never fully realized. Yet these fragile intimacies are swiftly undercut. In a gesture reminiscent of Barrie Kosky’s house style, solemnity collapses into provocation: at the court of the High Priests led by Daniel Dodd-Ellis’ redolent portrayal of Kajaphas, sacred ritual gives way to unabashed sexual spectacle – half parody, half burlesque.

Koen Schoots delivers high-octane musical leadership, driving both orchestra and amplified rock band with relentless propulsion – two guitars, pounding drums, keyboards, electric bass – the whole hangar vibrating with sound – to the more conservative opera public’s ears surely too loud, the nuances simply bludgeoned away.

By evening’s end, Hangar 4 feels less like theatre than a furnace: bodies, instruments, lights, and sound whipped into communal euphoria, especially during the famous encore, with the audience joining in. One cannot deny the Komische Oper’s command of scale or its ability to electrify a crowd. Yet one leaves wondering whether Webber and Rice’s work – already a creature of its era – gains depth from this inflation, or merely volume.