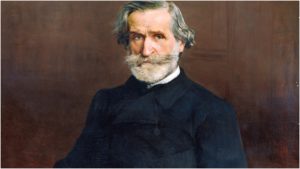

4 Reasons Why Giuseppe Verdi’s Art Remains As Relevant & Powerful As Ever

By David SalazarNext to Richard Wagner, is there an opera composer that stands as tall as Giuseppe Verdi?

Born on Oct. 9, 1813, the composer’s output far outpaced many opera creators before and after. But what is most fascinating is that his works endure to this day. While some of his greatest works have always held a spot in the operatic canon, spots that have never been threatened, lesser known operas from decades ago, such as “I Due Foscari,” “Giovanna d’Arco,” or “Atilla,” have suddenly found themselves unshakably fixed in the modern canon. Even composers of the past that are getting revivals of sorts can’t quite claim the same status.

So what makes Verdi’s opera so enduring and ever-fascinating? Throughout history, many of his works have often been criticized for their melodramatic plotting, much of which lacks narrative consistency. Exhibit A: “Il Trovatore.”

And yet, here we are. Verdi remains king of the opera world. Here are some reasons why.

Care for Characters

While there is no doubt that some of Verdi’s characters are among the greatest created for the opera stage (see Otello, Falstaff, Filippo, Nabucco, Simon Boccanegra, the Macbeths, Rigoletto, Gustavo, etc.) there is also no doubt that there are many stock characters layered throughout his works, particularly in the early ones. And yet, can one ever claim that Verdi overlooks a single one of them. They say that there are no small characters and Verdi certainly follows this idea.

Moreover, his villains are never truly one-sided. The great antagonists of such operas as “Atilla,” “Don Carlo,” and “I Vespri Siciliani,” are more than just men on vengeful rampages and the likes. Instead, Verdi always reveals more than one might imagine and actually makes us not only empathize with these characters but actually sympathize. Even the hateful Duke of Mantua is loveable to the audience because of how Verdi infuses him with an infectious melody.

Strong Women

In keeping with the theme of strong characters all around, there is no doubt that much of the appeal for Verdi’s operas is his strong women. Obviously, he has his share of damsels in distress, but none of the Verdi operas feature passive women sitting around for men to save their lives. Due to the context of his plots, the women in his operas are often forced into situations where they don’t have complete control, and yet we see them constantly shifting the balance of power in their favor. Violetta is probably the greatest of Verdi’s heroines, but one cannot overlook such women as Luisa Miller, Odabella, Abigaile, Lady Macbeth, Aida, Amelia (in “Un Ballo in Maschera”), and Azucena and how wonderfully complex they are. It is no surprise that the greatest mezzos and sopranos in history have, at some point, taken on and championed Verdi’s operas.

Relevant Themes

Verdi’s melodramas remain so poignant because they tend to be so relevant. Unlike many other composers of the time and since Verdi’s own life as a political figure is showcased tremendously throughout his operas. His ability to see how a figure struggles to balance his personal and public lives remains an issue for people of all professions. And the great tyrants and even benevolent leader of his works, are often shown with their failings. Just look at the guilt-ridden Macbeth or King Filippo, both lonely men who in their aims to maintain power have lost their connection to other people. Or Simon Boccanegra, a man thrust into a position of power he never wanted and forced to take on the consequence of that choice. We see people battle for liberation on one end and see oppressive regimes try and enforce their ways of life. We see an examination of the horrors of religious institutions and yet we ultimately see a reconsideration of man’s relationship to a higher deity. Man and his position within society is almost always at the core of Verdi’s works.

Parental themes are more prevalent in Verdi’s operas than they are in any other composer before or since. In many ways, these relationships are among the most poignant in all of the composer’s oeuvre. The reunion between Simon Boccanegra and his daughter Amelia is among the most beautiful moments ever scored. Ditto for Rigoletto and Gilda’s series of duets that develop their relationship throughout the opera. The ambiguity between Manrico and Azucena is a rich portrayal of love and hate in a mother-son dynamic. And there is also a truly tragic dimension to the relationship between Don Carlo and his father Filippo, who actually prefers his friend Posa to his own son. Everywhere you look, these relationships and the themes they highlight are revealing and ever-fascinating.

Infectious Melody & Thrilling Dramatic Music

Of course, you didn’t expect me to overlook probably the single greatest reason why Verdi’s art endures to this day – his music. He composed some of the greatest music ever written. Any Verdi opera, even his lesser works, is one stream of endless melody after another. Even his recitatives are hummable. This makes for dynamic emotional experiences with the composer constantly finding new ways to keep the audience engaged. “Il Trovatore,” which I mentioned in the intro, endures because of the three above reasons, but mainly because it is arguably the greatest example of the composer’s melodic wealth and imagination.

His final opera, “Falstaff,” doesn’t have as many “memorable” melodies as some of his earlier works, and yet the opera has just as much or more abundance of melody than any of his other operas. It’s just that Verdi has developed tremendous skill at this point that he has fused his gift with witty dramatic ability. Falstaff never wastes a note, which holds true for many of his other greater works.

One thing that makes Verdi’s music so wonderful is how he constantly plays with the limits of structure. More than any other composer, a look at his career progression showcases a man constantly looking to better himself. And by the time we get to “Otello” and “Falstaff” and compare them to “Oberto” and “Un Giorno di Regno,” there is no doubt that he has achieved that emphatically. The latter two operas test and surpass the limits of what Italian Opera signified, taking time-honored clichés showcased in those first two works and transforming them into dramatic gestures. Is there a drinking song that so wonderfully depicts increased inebriation the way “Otello’s” does? Or is there a more hilarious use of the A-B-A aria structure than the 30-second “Cuando era paggio” from “Falstaff?”

Verdi’s opera endures because it remains a discovery for those working in the art form today. And it will continue to do so as long as the art form is alive and well.