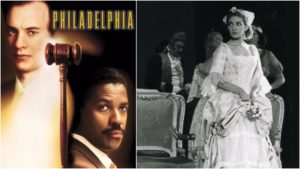

Opera Meets Film: Analyzing the Transcendent Power of the Maria Callas Scene From Jonathan Demme’s ‘Philadelphia’

By David Salazar“Opera Meets Film” is a feature dedicated to exploring the way that opera has been employed in cinema. We will select a section or a film in its entirety, highlighting the impact that utilizing the operatic form or sections from an opera can alter our perception of a film that we are viewing. This week’s installment features Jonathan Demme’s “Philadelphia.”

Opera permeates the structure of Demme’s famed film “Philadelphia” in a number of ways. In many ways, this essay could be about how the use of opera as a leitmotif in this film is itself explored as a deeper theme of hiding in the film, but that will be for another day.

Instead, this piece will focus on the major moment that everyone identifies with this film – Maria Callas and Tom Hanks.

The scene comes in the second half of the film with AIDS patient Andrew Beckett and his lawyer Joe Miller growing closer as friends. To this point, Miller has been homophobic, but he has started to turn against some of his prejudices and accept Beckett as a human being. THE opera scene ends up being the linchpin of their friendship. What Demme goes on to do is emulate opera itself in this one scene, expressing different ideas the way the older artform would.

As Beckett himself notes, we are listening to Callas’ recording of “La Mamma Morta” from “Andrea Chénier,” the ailing protagonist literally ignoring a plot-related question from Miller, effectively stopping narrative progression in favor of emotional reflection, much in the same way an opera aria would. Interestingly, Beckett narrates and translates what Callas is singing to mirror, though this device makes the audience feel Hanks’ character is also, in his own way, singing with the aria and expressing his deepest emotions. It is through opera that we see Beckett experience a level of emotional catharsis and vulnerability that has not been explored in any other moment of the film.

But opera is not only expressed through what is sung. The music itself, often providing context and subtext, also expresses itself without the need for text. Demme explores this concept through his other character in the scene. Throughout, Washington’s Miller is framed using a slow dolly-in, the actor just staring at his counterpart, the expression one of mysticism, searching, perhaps even longing. We don’t quite know and don’t get any answers from Demme. It isn’t really about that, but about the emotional depth of the moment that music can provide. We don’t need to fully understand it; we just feel it. That’s what opera does and Demme emulates that in this very scene.

Furthering this sense of emotional transcendence is the way he shoots the close-ups on Beckett – from above and with expressive red lighting. It takes us out of the proposed “realism” of the film for the moment (though to be fair the film has a number of stylistic flourishes throughout, such as constant looks right at camera during dialogue scenes) but ties into the theatricality of the operatic experience. If Maddalena is taking a moment to express her pain and suffering, then this is Demme’s way of doing the same with the visual medium.

But Demme goes further as Miller leaves the room and the aria starts playing once again. One thing worth noting is that to this point in the film, opera has only been associated with Becket’s character. We’ve only heard operatic voices with Beckett. But as we leave the apartment with Miller, the music plays on. He arrives at home and continues hearing Callas’ voice. It haunts him, much as it haunts the audience. Much the way that the great masters transformed the emotional meaning of leitmotifs in their repetitions, Demme evolves our own relationship with Callas’ “La Mamma Morta.”

It began as an aria introduced and translated by Beckett word for word. We know its meaning on the surface level from the text and context in the story. Then we feel it transform in front of our eyes through Hanks’ performance and Washington’s arresting look. And then we feel it haunt us and confuse us as it does him in the ensuing scene, its impact more transcendent than the text implies.

The only thing we know for sure is that he has connected, through art, with Beckett, the man he once judged and reviled for his homosexuality, on a deeper level.