Why Opera Is Not Just Heritage – And How to Keep It Alive

By Dr. Zoran MilosevicInstitutions often outlive their original purpose. Empires collapse, churches lose congregations, universities change beyond recognition, but the rituals remain, transformed into heritage. The question is whether opera is heading the same way: admired as a monument, but no longer essential.

Opera was once the ultimate multimedia art form, fusing poetry, music, theatre, and design. For centuries it stood at the centre of European culture, drawing kings and commoners alike to witness stories that captured the full spectrum of human experience. In that sense, it has already fulfilled its historic mission.

Today, cinema, musicals, and even narrative video games carry forward opera’s integrative role. Opera no longer sits at the cultural centre. It is easy to think of it as a tradition to be preserved rather than an art form to be lived.

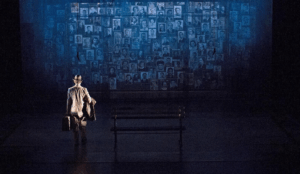

Yet opera is not like a painting or a novel, complete in itself. It vanishes unless recreated by singers, musicians, directors, and audiences. That dependence means it can never be entirely fossilized. As long as it is performed, it remains alive. But alive in what sense?

The Living Art Form

The challenge is not whether opera belongs to the past, but whether it can speak to the present. Some see it as museum culture, beautiful but distant. Others point to renewal through bold stagings, new commissions, technology, and cinema streaming that brings performances to millions who might never enter an opera house.

But renewal is controversial. Regietheater and radical stagings are often frowned upon by traditional audiences who feel betrayed when “La Bohème” is set in a modern refugee camp or when “Don Giovanni” becomes a tech billionaire. Their resistance is not trivial: opera carries memory, and memory resists disturbance. These works have accumulated centuries of interpretive tradition, and each production either honors or challenges that legacy.

Yet without reinterpretation, opera risks becoming ritual repetition. The very fact that audiences argue so passionately about these productions, walking out in protest or defending them with equal fervor, shows that opera still matters. Indifference, not controversy, would signal its true death.

These disputes point to a deeper divide that has shaped the field for decades: should opera’s future lie in constant creation, or in deeper devotion to the canon?

The Great Divide: New Works or the Canon?

The Traditionalist View: The canon is vast and still underperformed. Many operas by Händel, Donizetti, Massenet, Gounod and Mascagni remain neglected, gathering dust while companies chase headlines with difficult new works. Loyal audiences often feel alienated by productions that seem designed to shock rather than illuminate, or by atonal scores that satisfy critics and institutions but fail to win hearts. Why abandon proven masterpieces for uncertain experiments?

Traditional opera lovers have a point. When a company stages a forgotten Rossini comedy with wit and style, audiences discover works that feel both historical and immediate. The canon is not a museum collection, but a living library of human stories told through music of enduring power. Tradition, they argue, is not retreat but strength: the masterpieces are enough if performed with imagination and care.

The Modernist View: Opera was always new. In Verdi’s time, audiences came to hear last year’s premiere, not works from the past century. “La Traviata” shocked Victorian sensibilities with its portrayal of a courtesan; “Salome” was banned for its decadence. To deny new works is to betray opera’s essence as a living form that has always pushed boundaries and challenged audiences.

Contemporary commissions, even if uneven, allow the stage to speak to today’s anxieties about climate change, migration, technological disruption, and social inequality. Without risk, no new classics can emerge. The works we now consider untouchable masterpieces were once controversial experiments.

Finding Balance

Opera probably needs both approaches. Without tradition, it loses its roots and the accumulated wisdom of centuries. Without innovation, it ceases to grow and risks becoming a beautiful corpse. Its uniqueness lies precisely in this creative tension between preservation and transformation.

Consider what makes opera irreplaceable: it does not imitate life; it magnifies it. Characters sing instead of speaking, emotions swell into arias, conflict becomes sound itself. What might seem artificial, like people dying in elaborate melismas, is in fact a way of reaching truths that ordinary speech cannot touch. That excess, the unamplified human voice against the full orchestra, is not a flaw but a declaration. Opera survives because it insists on being more than ordinary life.

This is why opera cannot simply be preserved like a historical building. Each performance creates the work anew, filtered through the sensibilities of contemporary artists and audiences. A 2024 production of “Carmen” inevitably speaks differently about desire, freedom, and violence than one from 1875 or 1950. The music may remain unchanged, but its meaning evolves.

The Digital Revolution

Technology offers both opportunities and challenges. HD broadcasts have introduced opera to global audiences, making the Metropolitan Opera’s productions accessible from rural towns to major cities worldwide. Subtitles have broken down language barriers. Streaming platforms allow repeated viewing, letting audiences develop deeper relationships with works they might see only once in a traditional setting.

Yet something is lost in translation to the screen. Opera was designed for the scale and acoustics of the opera house, where the physical presence of performers and the collective experience of the audience create an irreplaceable energy. Digital formats risk turning opera into another form of entertainment rather than the unique communal ritual it has always been.

The challenge is using technology to enhance rather than replace the live experience, perhaps through augmented reality that adds visual layers to performances, or through innovative streaming that captures not just sight and sound but the atmosphere of shared witnessing.

Practical Ways Forward

If opera is to thrive in the 21st century, imagination must accompany preservation.

- Commission New Works Strategically: Rather than demanding instant masterpieces, companies should support composers through workshops, staged readings, and gradual development. Give today’s composers space to tell stories of our time, but also time to find their operatic voices.

- Rethink Staging Without Abandoning Meaning: Directors should take interpretive risks, but in service of the work rather than as statements about their own cleverness. Bold stagings work best when they illuminate rather than overshadow the music and drama.

- Expand Venues and Formats: Opera can live in schools, public squares, and intimate theatres, not only in grand houses. Shorter, more accessible works can serve as gateways to longer masterpieces. Pop-up productions and site-specific performances can reach new audiences.

- Invest in Education and Outreach: Early encounters with opera break down myths of elitism. School programs, young artist initiatives, and community partnerships can cultivate future audiences and artists.

- Use Technology Wisely: Streaming should complement, not compete with, live performance. Innovative use of digital tools can enhance storytelling and accessibility without compromising opera’s essential liveness.

- Embrace Cultural Diversity: Opera’s future may depend on composers and stories from beyond its European origins. Works by composers from Asia, Africa, and the Americas can expand opera’s emotional and musical palette while honoring its tradition of musical storytelling.

Conclusion

If institutions can survive as heritage, opera cannot. It lives only in performance, only in the fragile moment when voice meets orchestra and story becomes song. Unlike a cathedral or a painting, it exists nowhere else, not in scores, not in recordings, but only in the irreplaceable encounter between artists and audiences.

Its future will depend not on nostalgia but on courage, the courage to risk, to reinterpret, to keep speaking in a language of intensity that no other art form can match. Opera survived the rise of cinema, the advent of television, and the digital revolution not by hiding from change but by adapting while maintaining its essential character.

That is why opera, far from being a relic, remains necessary. In an age of algorithmic entertainment and digital distraction, it offers something increasingly rare: the undeniable presence of the human voice, the shared experience of live performance, and the ancient power of music to transform story into something larger than life. These are not museum pieces, but urgent reminders of what art can be when it refuses to settle for anything less than greatness.

Categories

Editorials