Vicenza In Lirica 2020 Review: L’Olimpiade

A Young Cast Shows its Potential in an Overcooked Production

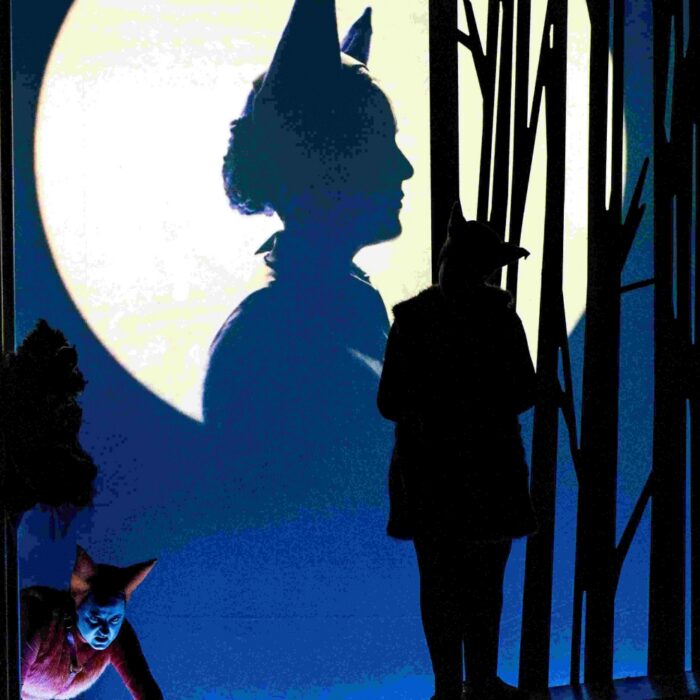

By Alan Neilson(Photo: Michel Crosera)

Vicenza in Lirica closed its 2020 festival with a second performance of Vivaldi’s opera “L’Olimpiade.”

Written to a libretto by Metastasio in 1734, it received its premiere at Venice’s Teatro Sant’Angelo. Yet, the work struggled to establish itself and had to wait over 200 years before it eventually received a revival, this time at Siena’s Teatro dei Rozzi in 1939. Although there have been a number of performances since then, they have more often taken the form of concert performances, so this was a rare opportunity to see a fully staged representation.

And what better venue could be have been chosen than Palladio’s Teatro Olimpico with its statues of classical Greece surrounding the auditorium and its fixed set of ancient Thebes adorning the stage.

Set in the Arcadian golden age, the story revolves around the usual themes found in baroque opera, of a competing love interest, disguises, and mistaken identity, which allows the singers to display their skill in depicting a series of emotional states. What raises this libretto above the norm, however, is that it is one of Metastasio’s finest texts, in which he combines dramatic intrigue with elegant poetic expression of rare beauty. In fact, Vivaldi was not the only composer to set the text, there being possibly as many as 50, with the honor of the first setting belonging to another Venetian composer, Vivaldi’s contemporary Antonio Caldara.

Overcooking the Present

The director Bepi Morassi took the imaginative decision to update the work to the present day, although with a neat twist by setting it in a museum with the protagonists of the drama cast as statues who come alive once the public has left. This worked on many levels, not least in that he could take advantage of the Olimpico’s fixed set with its many statues and its ornate bas relief sculptured set, which would grace any museum in the world.

Carlos Tieppo created a suitable array of costumes that cleverly combined baroque and classical aesthetics, colored off-white to create the appearance of statues, with the exception of Licida, whose attire was a mixture of grays and whites.

During the opening sinfonia, the cast wandered onto the stage and took up statuesque poses, followed by two porters who, shocked and frightened by the statues coming to life, quickly ran off in a panic. So far, so good!

The problem was that Morassi took the idea too far.

He clearly enjoys directing comedies and is very good at it. Moreover, he does not like an opportunity for more comedy to be wasted, and the role of the two porters offered him plenty of ammunition so that many scenes dissolved into the comic. The porters were not frightened for long and started to interact with characters, taking photos with their mobile phones, wheeling a character off the stage on a trolley and so on. Obviously, he could not let the COVID virus go to waste so that the porters wore masks and had hand gel available to keep themselves safe.

“L’Olimpiade” is however not a comedy. It is a refined reflection on serious issues such as political ethics, the conflict between love and duty, realization, and developing maturity. Certainly, it is possible to treat such grandiose themes with a light touch of humor, especially when the intricacies of the plot can appear quite ridiculous to 21st-century eyes, but on occasions Morassi had his two porters playing up to the extent they undermined the performers as they sang. His idea was good, but he misjudged the balance.

Notwithstanding his comedy excesses, Morassi’s experience of the theatre ensured that he kept the drama moving at a brisk pace, crafted many engaging scenes, and expertly developed well-defined characters.

A Young Team

The singers were uniformly young and in most cases light on experience. Although each of them produced a good, and in one or two cases excellent, performance, it would be fair to say that they are still “works in progress,” in which their full potential has yet to be realized.

The most complete performance of the evening came from mezzo-soprano Emma Alessi Innocenti in the role of Megacle, who disguised as his friend Licida, competes in the Olympic Games (hence the title of the work) to win the hand of Aristea. She produced an expressive performance without compromising accuracy. In the passage of accompanied recitative, “Che intesi, eterni Dei!” she sang with passionate intensity, molding her phrasing intelligently to reflect the meaning of the text, whilst maintaining the clarity of the voice. Her voice has a pleasing tone, which brightens beautifully in the upper register.

The aria, “Lo seguitai felice,” was splendidly rendered, in which she decorated the vocal line with pleasing ornamentations and colorful intonations, along with a smooth, controlled if not flamboyant coloratura. Moreover, she also convinced in a male role.

Mezzo-soprano Francesca Lione produced a self-assured, well-acted portrait of Argene, who as a princess disguised as a shepherdess seeks to track down her lover Licida. Her vocal technique showed considerable maturity, in which she displayed careful attention to the presentation of recitatives and to developing her character, nicely capturing the refined nature of a princess beneath her shepherdess’s clothing.

Likewise, arias were presented confidently and with emotional depth. The voice is flexible with pleasing timbre, which she imbued with a variety of colors and neatly placed emphases, in what was an intelligently and thoughtfully rendered performance.

The countertenor Sandro Rossi displayed considerable potential in his essaying of the demanding role of Licida. Rather than playing it safe by focusing on accuracy, he despatched his arias and expansive passages of recitatives with the emphasis on expressivity and emotional truth, to which his voice is well-suited.

In the fast moving aria, “Quel destrier, che all’albergo è vicino” he displayed considerable vocal versatility, while in the graceful aria “Mentre dormi, Amor formenti,” he showed off the beauty of his voice, in an elegant, secure presentation in which he subtly ornamented the vocal line.

The aria, “Gerno in un punto e fermo,” was given a full-blooded presentation, with Rossi attacking the lines, the voice, full of passion as he moved up and down the stave, with the orchestra racing along in typical Vivaldian style, full of zest and energy. Despite certain flaws, it was an excellent performance, one in which his identification with the character was clearly visible.

The soubrette soprano Maddalena De Biasi, in the role of Aminta, received the loudest applause of the evening for her performance of the aria, “Siam navi all’onde algenti,” in which she let loose her light, bright, extensive coloratura, as she danced across her higher register with ease. Impressive as it may been, unfortunately, her projection was inconsistent and she often disappeared beneath the sound of the orchestra, which undermined the overall effect: it is something which she needs to address as it as a voice worth hearing.

One of the more experienced members of the cast was baritone Patrizio La Placa in the role of King Clistene. He produced a well-rounded portrayal, in which the dark colours and engaging tone of his lower register appealed. His final, albeit short aria, “Non so donde viene,” was particularly successful, which he gave in a confident, clear rendition, highlighting the voice’s textural qualities.

Aristea was played by Daniela Salvo, who is in love with Megacle, but has been awarded as a prize to Licida by her father. She possesses a fairly strong, flexible voice with an attractive timbre, which she embellished with an array of colors, but her articulation was not always clear, having a tendency to swallow her words on occasions.

The first act aria, “È troppo spiegato,” in which she is in a state of distress, allowed her to show off her vocal versatility, her pleasing coloratura and ability to develop her character through the voice. Her duet with Megacle, “Ne’ giorni tuoi felice” was well-coordinated, with Salvo and Innocenti’s voices overlapping and combining in a nicely designed piece, the colors of Salvo’s voice contrasting beautifully with Innocenti’s brighter timbre.

The bass Elcin Huseynov was cast in the role of Clistene’s confidante, Alcandro. He possesses an engaging, layered voice with interesting depths, which he used skilfully to characterize the role. His phrasing was neatly crafted and secure, displaying a substantial degree of versatility.

The conductor Francesco Erle elicited a rhythmically vibrant reading from Ensemble Barocco del Festival Vicenza in Lirica, in which drew out the colors from Vivaldi’s score, and paid close attention to the needs of the singers.

Owing to the COVID emergency, the theatre had to abide by a time restriction on the length of performance which meant a number of cuts had to be made, but this was well-managed and did not noticeably detract from the overall performance, which was hugely enjoyable and brought the festival to a successful conclusion.