The Greatest Moments In Wagner’s Operas, Per OperaWire’s Staff

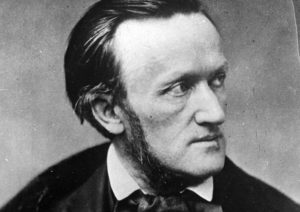

By OperaWireRichard Wagner, born on May 22, 1813, is arguably opera’s most famed revolutionary. His music creates a wide range of emotional reactions from his audiences. Some people are completely obsessed with his music and can’t really consider anyone near his level. Other enjoy it in bits and pieces but might find the lengths of his works challenging. Others still outright hate him.

But there is no denying that his music includes some truly breathtaking moments and in celebration of his birthday, OperaWire’s writers were asked to breakdown a favorite moment from a Wagner opera. You’ll not a wide range of approaches to this, including some perspectives on how a particular moment was illuminated by a specific production.

What is your favorite Wagner moment? Let us know in the comments below!

John Carroll

I’ve never been a Wagnerite, so I am selecting the one Wagner passage I do know very well: Brünnhilde’s Immolation Scene from “Götterdämmerung.”

Years ago an opera buddy of mine made me a mix-tape of about 10 different diva recordings of this piece as a way to lure me into a more evolved appreciation of Wagner. The strategy worked to the extent that I know this monumental aria so well I could probably conduct it (with a little coaching, of course). And the bonus is that since this 20-minute scene contains so many of the primary leitmotifs from the whole Ring Cycle, I feel like I know the whole work. And for the purposes of this article, it doesn’t hurt that the Immolation Scene is the apotheosis of Wagner’s greatest musical achievement and the pinnacle test of a dramatic soprano’s stamina and artistry.

I have two moments within this long scene that take my breath away every time. First is the short section from the first mention of the ravens to the phrase, “Ruhe, ruhe, du Gott.” Then there is the final section when Brünnhilde calls out to Grane, her steed. It does me in that she sings to her faithful horse before riding him into the flames of her lover’s funeral pyre, ending her own life and bringing about the end of the world.

Matthew Costello

Picking a favorite moment in a Wagner opera? Interesting, because, in my opinion, Wagner’s works are filled with amazing moments. The unique power and beauty in his operas is probably what led to the passion so many had for this “Music of the Future.”

But for me, there is indeed one to single out: the Good Friday scene in Act three of “Parsifal,” where Parsifal returns, on this most sacred day, to become the leader of the Grail knights.

So why this “moment” above all others? For me, the holy day and other-worldliness of Parsifal’s return brought out perhaps Wagner’s most magnificent composing. It probably doesn’t hurt that I spent years — when young — at Good Friday services, the most solemn day always seeming to look and even feel differently from other spring days, despite what one believed. And “Parsifal” — in this scene — magically captures that.

Sophia Lambton

Polina Lyapustina

If I would have to choose a single moment from Wagner’s operas to listen to everyday of my life, it would be “Inbrunst im Herzen, wie kein Büsser noch” from the third act of “Tannhäuser.”

First of all, this aria requires an extremely well-developed and flexible dramatic tenor voice. The range is wide, the sound is very intense. In this scene, the true personality of a broken man, losing his last hope, finally overcomes all the other ostensible traits of the title character. It is also a very complex and rich piece, which surely contains many of signature Wagner’s techniques, such as long phrasing, melting leading melodic lines, and — going back to the beginning — it’s all about deep and dark tenor voice, and no one could compose such piece better than Wagner.

Christopher Ruel

Wagner for orchestra, yes! Wagner as operatic theater, no thanks. I admired the composer as a proto-film composer, enjoying the moments in which I would discover bits and pieces borrowed—ahem—okay, entire themes stolen by those composing for Hollywood. But the idea of taking in five or more hours of through-sung opera didn’t hold much appeal. I was content to float upon the surface until I saw “Parsifal” at the Met under the direction of Yannick Nézet-Séguin.

Experiencing Wagner’s final opera was, as many have described, a spiritual encounter with music. It took me weeks to process what I had heard. The effect of the opera was deep-felt. I studied the “Prelude,” entering much of it note by note into Finale, as I attempted to understand some of the mystery within the simplicity. Story-wise, the character of Kundry held fast in my psyche, so much so, I began sketching an idea for a work of fiction that would focus solely on her plight. (The concept hasn’t been abandoned.) I admit I became a bit obsessed, but that speaks to why I’ve named it as my Wagner favorite—I can’t get it out of my brain.

“Parsifal” may have been a strange door by which to enter Wagner’s world, but this oddly serene work sparked an enduring desire to continue to dive deep into Wagnerian waters. And, as with so many opera composers, it will be a lifetime swim.

David Salazar

Wagner was a genius and that stems from his operas having a transcendent quality that few other composers could rival. We see that in his greatest operas, especially “Parsifal” and the entirety of the “Ring Cycle.” We see that in “Tristan und Isolde,” arguably the most incredible marriage of opera and philosophy the world has ever known.

Originally, my choice was going to be the ending of “Tristan,” simply because of the sense of release and this very transcendence that cannot be found anywhere else in opera. After several operas of unresolved harmonic development, we finally get to that glorious B major chord we’ve been waiting for. This is arguably the longest and greatest payoff in all of art history.

But instead, I am going to go in a very different direction with “Selig, wie die Sonne” from “Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg.”

Wagner himself repudiated the conventions of opera and in his famed 1851 essay “Oper und Drama” he noted that his new music drama would make the conventional ensembles of opera unnecessary.

He eventually came around on some of those radical ideas and found ways to reincorporate them into his greatest works. This might simply be the greatest ensemble he ever created.

Harkening back to his love for Bellini and his expansive melodies, the quintet initiates with Eva getting a solo line that eventually brings in the other characters one at a time. Eva, who is at the core of the drama remains the focal point throughout, with others working in reaction to how her melody evolves. More beautifully, her initial melody eventually grows into Walther’s Prize song, emphasizing their deeper connection through music. It is at this moment, when she takes up this melody that Sachs and Walther join in. Walther sings his song alongside her while Sachs counters it, further emphasizing the emotional connections and distances. Meanwhile David and Magdalene sing their own harmonic accompaniment, emphasizing their love.

A descending line eventually takes over, with the four characters repeating it (Eva, of course being the exception), eventually climaxing in fragments of all the melodies coming together. For good measure, Eva gets to conclude it all with a potent high note, which undeniably would be a part of the traditional Italian ensemble that Wagner here incorporates in his opera.

Wagner, of course, is not the first to so perfectly explore character through the ensemble, but this is a powerful inclusion in his greatest masterpieces. It is a rare ensemble and his placement is cathartic. It is the emotional climax of the entire opera – the point where Hans Sachs finally resolves to resign himself from his love for Eva and do what he can to help her and Walther be together blissfully. There is still a contest to be won, but it seems like a foregone conclusion after the sublime beauty of the quintet. In fact, the ensuing scene comes off as a lengthy epilogue.

“Simplicity is the ultimate sophistication.” This was never truer than this very ensemble.

Lois Silverstein

The moment I loved in Bayerische Staatsoper’s “Parsifal,” June 2018, was the moment of recognition that occurs in the finale of Act II, when the “world,” the structure around Klingsor, collapses. It is the moment following Parsifal’s confrontation with the Magician, and when he realizes and acknowledges his actual power.

The moment is cumulative, of course, building from the first moment Parsifal, Jonas Kaufmann in this production, races onstage hugging the swan he has just killed. His power here is based on scarcity, limitation, fear. He must protect his catch, the “fool” that is Parsifal, hugging and hunkering down over the dead bird. This rises from ignorance, innocent ignorance. He knows nothing more than survival of body. The moment preceding the collapse of the castle – the attempted seduction of Parsifal by Kundry and her handmaidens – mimics this limitation. Again, Parsifal is wrapped in the temptation of the senses. We follow him and succumb as he does, but only for an instant. Then his trances snaps. Parsifal has awakened, and so do we.

By the end of the act, after Kundry and Klingsor have been pushed away, Parsifal steps further from such dullness and begins his rise into his true strength and power. This is the moment: when he faces off his wobbling human center, its beckoning, its calls, and thrusts himself up into a fuller human one, the moment when he recognizes his capacity as a human being. It is this that pulls the walls down. He rises, Kaufmann’s Parsifal steady, steadfast, looking forward, asserting without excess, without aggression, and with that the walls fall. It is a brilliant moment, not the finale, but its preface. It is the human moment, when Wagner made sure Parsifal was prepared for what was to follow, the transcendent wisdom of Act three and the order of the Grail. What moved me in this production was just this human awareness, the moment before we lift from the ground, when all else crumbles. Perhaps we sense we are on the cusp of something more; perhaps not. No matter. We assume the fullest dimension we can at this time, and for that moment, it is enough.

In this performance, Wagner’s vision came to life, from tree to falling building to starry universe. Kirill Petrenko in the pit contained and sustained the harmony of the whole. Nothing held Wagner, poet and composer, prophet and dreamer, back. No gap existed between vision and reality, past and present, word and sound. The prodigious energy of the world he created lived far past its performance. Even if you despise the man, even if the music bores you, even if you have no idea what he is aiming at – myth and history, byway and main road, love and death, power and loss, vision and dream, squared – that night he had us, and still we do not let go.

Jonathan Sutherland

If an intellectual titan such as Friedrich Nietzsche couldn’t make up his mind about Richard Wagner, what chance is there for mere mortals?

Even though Rossini quipped that Wagner had “wonderful moments but dreadful quarter hours” there could be no more supremely glorious 15 minutes of music than the close of his Bühnenweihfestspiel “Parsifal.”

From “Nur eine Waffe taugt” there is an ever increasing sense of profound serenity and spiritual calm which seems inconceivable from the composer whose fatalist if not nihilistic pessimism was already evident in “Lohengrin” 30 years earlier. There are no “Fliegender Holländer” redemptresses jumping into the sea or “Götterdämmerung” heroines riding horseback into blazing infernos. Even the ecstatic euphoria of “Tristan und Isolde” does not come close to the deeply cathartic sense of divine grace which permeates the last scene of “Parsifal.”

Yes, Wagner the person was an unashamed adulterer, bigot, anti-Semite and accomplished conman. But Wagner the composer was no doubt an honorary member of composers Valhalla.

No adequate consideration of “Parisfal” can be made without listening to the recordings of Hans Knappertsbusch who made seven commercial versions between 1951 and 1964. There have been many recent productions ranging from the ridiculous (Alvis Hermanis at the Wiener Staatsoper or Dieter Dorn in Baden-Baden) to the sublime which was arguably Otto Schenk’s 1991 production for the Metropolitan Opera with the 2003 cast of Domingo, Urmana, Struckman and Pape conducted by Gergiev.

Despite any number of irksome directional aberrations, the closing scene of “Parsifal” is unquestionably Wagner’s “Höchsten Heiles Wunder!”

Greg Waxberg

For a favorite moment by Wagner, I look to the Ring Cycle, and one scene always brings tears to my eyes and leaves me emotionally spent.

At the outset of Act two of “Die Walküre,” Wotan and Brünnhilde are happy-as-can-be father and daughter. By the end of Act three, Wotan says goodbye to her forever. What has changed? Her disobedience of Wotan’s orders, protecting Siegmund during the battle with Hunding, prompted by her love for her father, what she knew to be her father’s love for Siegmund, and her observation of Siegmund’s love for Sieglinde. Who among us has not been affected by our love for someone and by witnessing the love of others?

So, for me, that favorite scene takes place in Act three, with father and daughter alone in the wake of Brünnhilde’s disobedience; through reflection, she softens his anger. It begins with the woodwind melody that accompanies “liebe” in her explanation of the source of the love—Wotan—that motivated her actions (this melody has already been heard in fragments in this act, but now becomes prominent). Wagner briefly elaborates the melody after Brünnhilde’s use of the word “vertraut” (faithful), again referring to feelings toward her father.

During Wotan’s Farewell, this melody—which, to my ears, has always sounded like the orchestra crying—returns and envelops the entire orchestra, building to a gut-wrenching climax. Why is something so sad a favorite moment? Wagner’s genius with music and drama makes the listener feel the poignancy of love, of the parent-child bond, and, in this case, of the consequences once that bond is broken. This cathartic moment goes straight to the heart—the reason theater exists.

Gordon Williams

I have two favorite moments in Wagner. One shows how Wagner’s harmony speaks; the other graphically illustrates for me the meaning of Music Drama. First, harmony: In Act two of “Die Walküre,” Brünnhilde comes to tell Siegmund he will die in the duel with Hunding the next day. But Siegmund is not downhearted as long as he will see his beloved in Eternity. “Will Siegmund find Sieglinde there?” he asks, as his music modulates up a fourth, expressing his rising anticipation. “Erdenluft muss sie noch athmen; Sieglinde sieht Siegmund dort nicht,” replies Brünnhilde. In other words: “No”. But listen to the music cadencing a semitone lower than our ears expect, masterfully underscoring the disappointing message.

Is it music or is it drama, or both? At the end of “Das Rheingold,” there is a shimmering and swelling in the music which finally blazes forth in a proud, even harsh, assertion of triumphal power. The Gods are finally crossing the rainbow bridge into their citadel Valhalla. It’s pure, unalloyed victory. Or is it? Only if you’ve been paying no attention to the storyline. Because the gods are actually entering a kingdom that has been doomed; “hastening to their end,” as Loge says. If you only value Wagner for his music, you might miss one of theater’s most spectacular examples of irony.