The Church of Sweden 2023 Review: Johannes Brahms’ ‘A German Requiem’

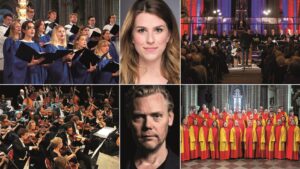

By John VandevertAfter several days of lethargic grayness, apathetic rain, and candid winds, what seemed like the entirety of the Uppsala community gathered within the walls of our local cathedral to bear witness to Johannes Brahms’ selfless petition to all of mankind. Organized by the Church of Sweden, an Evangelical Lutheran denomination as it so happens, three choirs of the Uppsala Cathedral were brought together under the sagacious baton of Ulric Andersson. Filling out the performers were two soloists, baritone Karl-Magnus Fredriksson and soprano Sabina Bisholt, along with a quasi-chamber orchestra provided by the Royal Academic Chapel Orchestra.

Before I am accused of sycophancy, for the performance was truly marvelous on every front, nothing is ever perfect. And yet, between the responsive choir, the erudite soloists, and the fine orchestral cohesiveness, there is little to anything worthy of complaint. Neither excessive nor lacking, all was as it should be, potentially the highest compliment I know. The music and its interpreters were all aligned, linked and listening between each other.

Background

Composed after and during personal tragedy, first being the death of his mother in 1865 and then his personal friend and champion Robert Schumann, “A German Requiem” is dually more than the sum of its parts. Much like Faure and his humanist compassion and Verdi with his theological conflagration, Brahms chose to write a Requiem which calls out to those who seek shelter from persecution, guidance in times of uncertainty, and a balm from unforgiving pain. It is no coincidence that the “young eagle” Brahms, as Robert lovingly called him, grew up in a Lutheran family and became attuned with the theology of the Luther Bible. For Martin Luther, music should be a human universal, openly available for anyone to honor and adore the divine pleroma of God’s transcendent effulgence. In his famous 1538 forward, Luther confidently states, “next to the Word of God, the noble art of music is the greatest treasure in the world. It controls our thoughts, hearts, minds, and spirits.” Luther went as far as to almost pair music with theology itself, “Music is a beautiful and glorious gift of God and close to theology.” Yet, most applicable in any evaluation of Brahms’ “human Requiem,” is Luther’s staunch belief in music’s sacred service and its role in the betterment of one’s fellow man and the world therein.

As Luther’s perfumed and unpretentious words are recorded, “For whether you wish to comfort the sad, to terrify the happy, to encourage the despairing, to humble the proud, to calm the passionate, or to appease those full of hate…what more effective means of music could you find?” Indeed, whether Brahms knew it or not, his Requiem was a pronounced testament to the paschal subliminality of the musical art, a magnanimous vehicle for self-sacrifice on behalf of the one true noble cause, and the aligning of the spheres which invites the regenerative Weltgeist of the eternal beyond into a fallen immanence. Brahms’ second title, “Ein menschliches Requiem,” is more evocative of its furtive intentions, escaping the composer during his life yet finding resonance in the world it is invoked today.

The Requiem is based on the Beatitudes, the eight blessings given by Jesus during his Sermon on the Mount, itself part of five discourses centered around uplifting the dubious and weary through teaching centering around the ethical and moral principles of Christian life. Effectively, to be in communion with God and the resplendency of his kingdom, one had to live in the spirit of God, the “Divine spark” which resides in each person irregardless of its acknowledgment. An alleviation of fear of separation, the sermon was a didactic method of realizing one’s relationship with God and for Brahms, the alleviation of suffering through music was his sermon. While, like Beethoven, Brahms’ relationship with religion was complicated and ambiguous but perhaps he was far more religious than many of us, especially those who claim true belief. For me, the evening spent among strangers under the painted ceiling and gilded pulpit felt truly divine.

Strong Soloists

Regarding the soloists, Fredriksson, a well-acquainted veteran of opera, oratorio, and all things therein, excelled as the strong voice of the supplicant. His unique blend of elegant phrasing, spinning cut, and sophisticated legato, cast a fortuitous light over his expanding career and undeniable reputation as a chevalier de l’opéra. His first solo, “Herr, lehre doch mich,” was executed perfectly, with his routine entrances into his upper register and bouts of drama showing off his robust tapestry of color and nuance. He also negotiated quite well the usage of portamenti to resurrect, if only for a short time given the classical singing we have today, the heydays of bel canto mysterium.

The type of liquidity which both soloists exuded in their curt, but not insignificant, solos during the evening’s performance were a unique mix of werktreue conscientiousness and regietheatre ownership. During Fredriksson’s second solo, “Denn wir haben hie keine,” a forthright consecration in the belief of an overcoming from mortal finality to divine immortality in the kingdom of God, his operatic confidence only grew in tenacity. Embodying the confidence of Verdian formidability, Frederiksson was the paradigmatic epitome of the cavalier baritone. His unrelenting, princely, and welcoming voice radiated in spinning majesty throughout his quite sizable register, while consummate technicality, which declamatory potency and charged melodicism only seemed to enhance, gave the evening the penultimate climax it dually required.

For Bisholt, much of the same can be said, although her time was unjustly cut short, no thanks given to Brahms who never could write for the female voice despite his best efforts. Nevertheless, Bisholt’s richly lyrical voice, quite at home with the bel canto tradition it seemed, was a marvelous compliment to Brahms’ more thickly intimidating musical language. During her solo, “Ihr habt nun Traurigkeit,” a hopeful promise of comfort from pain and toil from God to his people, Bisholt’s voice soared in colorful opulence throughout the cathedral, the dove looking for land after the divine violence of a new beginning. Her earnestness was easily detectable throughout her singing.

On the technical front, Bisholt’s voice was thoroughly grounded and was unflappable during escapades into the upper range. Her voice ached to be set free and yet Bisholt strategically utilized her operatic potential in all the right places. Without the contemporary affect, artificial pomposity so many sopranos tend to reach for to enhance a spotted instrument, Bisholt gave a performance where she spoke through Brahms and vice-versa, polluting the vision of the composer nor the individuality of the performer in the process. Despite the brief moment Brahms gave her, Bisholt gave a marvelously educated performance which demonstrated her astute, artistic abilities.

Palatial and humble in equal measure, declamatory and receptive, listening and speaking, hopeful and honest, the Brahms Requiem is a tribute towards a human realization of what God is and could be. Leaning into the sanguine and safe yet never watering it down for the sake of the bold and the brash, while Brahms’ writing can become excessive and indulgent to the point of shameless, tawdry bellowings of the intellectual sentimentalist, the Requiem is not one of those moments. The lasting impressions of Beethoven’s humanism, the transcendental Idealist notions of the external within the internal, and the easily detectable influences of Romanticism and German naturphilosophie, with its thesis of investigating the world and its structures, all paint the Brahms Requiem as the product of a specific moment in time. A tribute to the cessation of suffering, Brahms’ reach through man to God.

The road by which to perform an antiquarian Zeitgeist sacrificed for neo-Enlightenment reason and scientific “progress” is a challenging one. But it was, the zealousness of the Romantics to discover themselves through holistic union with nature was on clear display, albeit through a remarkably sacred lens. I had only wished it was longer but the apotropaic power of the dynamic contrasts from explosive motility to caressing fluidity was more than enough to hold me over for a while. God only knows how relevant Brahms’ “Requiem” will be as the days go by.

Categories

Reviews