Teatro Real de Madrid 2018-19 Review: Falstaff

Daniele Rustioni Leads a Memorable Production Directed by The Brilliant Laurent Pelly

By Mauricio VillaGiuseppe Verdi had only written a single comedy: “Un giorno di regno” and 26 tragedies before deciding to put music to the comical Shakespeare’s character “Falstaff,” his last composition.

Verdi had already started a musical development in his latest operas, more noticeable in his precedent work “Otello,” looking for different ways to create a perfect musical drama, breaking with the structure of arias, choruses and finale ensembles to create a musical continuum which would suit the action of the opera better. The result in “Falstaff” is a vibrant and eloquent comedy, using a lot of counterpoint in the voices and a perfect mixture of the orchestra with the voices to enhance the dramatic purpose of the plot. As in “Otello” there is no overture and the opera moves right into the action. The long Verdi melodies are still noticeable, but the lyricism is abbreviated, melodies bloom suddenly and the vanish, replaced by contrasting tempi or an unexpected phrase that introduces another character or idea.

Verdi was moving towards the kind of idiom that would come to dominate 20th century music.

Pelly The Great

The Teatro Real de Madrid, in collaboration with Théatre Royal de la Monnaie and Tokyo Nikikai Opera, premiered a new production directed by Laurent Pelly, and the result was quite satisfactory.

Pelly, who is famous for having created hilarious productions of Offenbach Operettas or comic operas like “L’Elisir d’Amore” and ”La Fille du Régiment,” gave a lesson about how to apply all his staging resources in order to create a frenzied show, amusing but thoughtful at the same time. It is true that we are accustomed to see colorful productions from Pelly and that this “Falstaff,” by comparison, seems grey and dark, but that is because he focused on the social and moral aspects of the story; the plot and the music are funny enough and there is no need to reinforce that.

Pelly directs his comedies as if they were Broadway shows, with a clear definition of the characters and creating big musicals numbers where all the singers on stage dance.

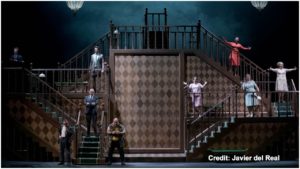

But in this case not only the performers moved continuously through the action but the sets too. Barbara de Limburg designed a claustrophobic bar with impossible perspective which expands or deforms according to the action, and a labyrinth of staircases which opens up to give space to the living room where Falstaff tries to seduce Alice in Act two. There is a black curtain which has the effect of a lens camera which centers the attention on characters or sets. There are moments in Act three where the stage is bare and dark and he plays with spotlights and the hide and seek movement of the characters. It’s incredible how he can do so much with so little.

Moreover, Pelly goes deeper into the characterization of the roles, so we see a fat old Falstaff who is filthy and dresses as a beggar. Upper class characters like Doctor Caius or Ford who have succumbed to greed and ambition are bald, wear thick glasses and wear plain dark suits. The “merry wives” sport Jackie Kennedy-styled hair and clothes, while and lower class characters like Bardolfo and Pistola appeared as street gang members. We have the male chorus dressed up as Ford in Act two, which leaves us with a dozens “Fords” running around the sets and staircases looking for Falstaff. Conversely, we see the all-female ensemble dressed up as “Alice” in Scene two of Act three. Even though you laugh a lot during the opera, you still have bittersweet feelings when the performance is over.

A Hilarious Swindler

It is difficult to analyze the voices in operas like Falstaff, because despite of some very few solo musical numbers like Falstaff “L’Onore” in Act one, or Ford’s “È sogno, o realtà” in Act two, most of the scenes are choral numbers where the vocal lines of several characters intertwine. Characters as important as Alice don’t have a single solo page moment. Therefore, you expect “Falstaff’s” cast of voices to blend well together, a perfect synchronization with the conductor and orchestra.

The cast that Teatro Real presented succeed greatly.

Misa Kiria, a Georgian baritone who debuted at Teatro Real, incarnated the title role of Sir John Falstaff. His voice is lyrical and projects. Moreover, his Italian diction immaculate. He gave a musical reading of the score emphasizing the long lines that Verdi wrote and caring for legato in the quick and parlatto moments, as there is a tendency to speak and scream this parts rather than sing.

He seems to have never ending resources to create dynamics and enrich all his moments. Although he used falsetto to imitate Alice’s voice in the phrase “Io son di Sir John Falstaff” as it is usually done, he managed to produce some wonderful pianissimi notes, like the high F in “ Di San Martino” and many more rather than persisting with the falsetto.

His high G at the end of his solo in act one in “L’Ònore” was vibrant and thunderous, being present over the forte sound of the orchestra. He reflected all the pathos of the character. You laugh at the actions that takes place, but Kiria makes you feel pity for Falstaff. He humanized the figure of this fat, old, presumptuous, and gluttonous swindler. It was hilarious to see a defeated Falstaff warming his feet in hot water at the start of Act three or seeing him rub his belly in attempts to seduce Alice.

Major Male Leads

Angel Òdena, a Spanish baritone who has been present at Teatro Real since 1999, recreated the role of the infamous jealous husband Ford. His voice has grown considerably but has developed an uncomfortable wobble in the middle and upper register. That said, Verdi’s final score fits him perfectly. His voice sounded secure, strong and stable and his multiple ascensions to high F sharp in his scene with Falstaff were impressive. His crude interpretation of “È sogno, o realtà,” sung to the audience as if the character was stepping out of the opera, was one of the highlights of the evening.

Fenton, the romantic lover, was sung by the tenor Albert Casals. The role of Fenton is very difficult to cast: the tessitura of the role is quite high, reaching a high B natural or flat in most of his interventions. Usually the high notes are within legato phrases, meaning that they must sound easy and effortless. He is also a young character, so the voice requires a bright sweet timbre. Therefore Fenton is usually cast with Lyrical leggero voices. Casals, who fits this voice type, demonstrated an incredible control and breath support in “Dal labbro il canto” with exquisite pianissimi and diminuendi on the several G and A of this page. His easy high notes, like the bright high B flat on the phrase “Ciglia assassine,” were sung in a perfect vocal “I” which is rather challenging. The problem with leggero voices, and Casals was no exception, is that they disappeared in larger ensemble as they can not surpass the density of the heavy orchestration that Verdi used or the rest of voices singing together. Although Fenton has quite a few solo moments and duets with Nannetta, he is singing (as most of the characters do) mostly in ensemble. Sometimes his vocal line, like in the second scene of Act one should be present as it is required by the harmony, so it is a shame when Fenton’s voice is swallowed by his mates and orchestra.

Laurel & Hardy

Mikeldi Atxalandabaso and Valeriano Lanchas were a like “Laurel and Hardy” in their roles Bardolfo and Pistola, the comical counterpoint to the sad and obscure figure of Falstaff. Atxalandabaso voice is just incredible, having a lyrical instrument that projects wonderfully. His voice is always presents, even in choral scenes, and his articulation, diction and phrasing are impeccable. No wonder he made his operatic debut in the infamous short but devilish role of the “Pêcheur” in Rossini’s “William Tell.” It was funny to see him running across the stage wearing a bridal gown during the very last scene of the opera.

Lanchas has a profound bass voice, his timbre might sound a bit dry, but it is rich in nuances. He has a big voice that he put into service to recreate a dumb delinquent who betrays his master Falstaff alongside his inseparable friend Bardolfo.

Christopher Mortgage, as Dr Caius, was the weakest of the male voices. Giving an arduous portrayal of the disagreeable doctor, his continuous abuse of plain notes and shouty lines blurred his musical interventions. It didn’t help that his pitch tended to be errant as well.

Merry Wives Indeed

The Merry Wives of Windsor were portray by Raquel Lojendio (Alice Ford), Rocío Perez (Nannetta), Teresa Iervolino (Mistress Quickly) and Gemma Coma-Alabert (Mrs Meg Page). With the exception of Nannetta, the rest of the female voices sing always appear in choral scenes. The four voices blended very well together and sang with perfect synchronization, something hard to accomplish in this elaborate score.

Lojendo, who possesses a beautiful Lyrical soprano voice, show how to sing a breathtakingly long line during “Ma il viso tuo su me risponderá,” a phrase which recalls the long beautiful melodies Verdi was famous for. She had no problem with the attack of the several high B naturals and C’s that her part has.

Perez has a wonderful lyrical leggera voice, with a crystalline timbre and flawless pianissimi demonstrated in her duet with Fenton in Act one and in “Sul fil d’un soffio etesio.” She performed a witty and spontaneous Nannetta who was unafraid of showing her passion for his lover.

Iervolino provided the comical touch, portraying a determined trickster lady who doesn’t doubt about drinking three shots of brandy before confronting Falstaff for the first time. It is a low part, usually entrusted to contralto voice with a lower register. Iervolino has the resonant low chest notes and proved to be an efficient actress. Coma-Alabert accomplished the role of Mrs. Meg Page honorably.

The choir of Teatro Real showed its professionalism and good singing in the very short interventions that this opera offers for them and proved their acting and dancing abilities throughout the many challenges that Pelly’s staging demanded of them.

The young Italian conductor Daniele Rustioni, who debuted at Teatro Real, gave a passionate reading of the score, not taking risks in tempi and managing to coordinate the voices with the orchestra perfectly. He ended the performance with a triumphant and lively performance of the fugue “Tutto en el mondo è burla.”