Teatro Real de Madrid 2023-24 Review: Rigoletto

By Laura Servidei(Credit: Javier del Real)

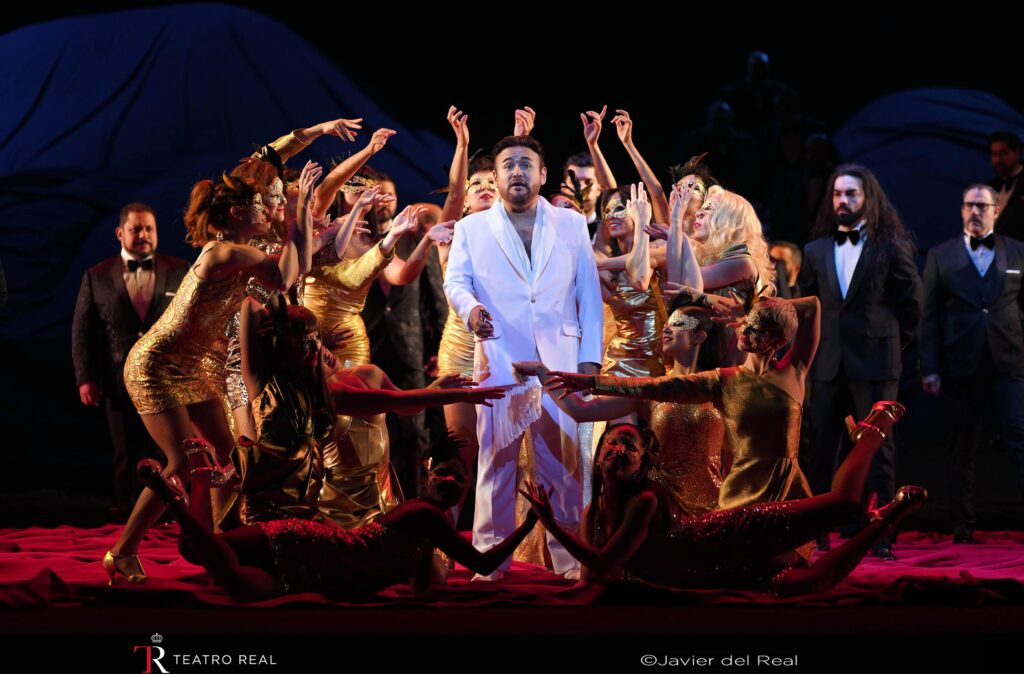

A woman’s whimper, a stifled scream, echoes in the dark. She flees into the theatre, amidst the stalls, chased by a few men in ominous rabbit masks. She seeks refuge on stage, terrified in front of the bright red curtain, the pack hunts her down, overpowers her. The trombones attack the prelude, with haunting repeated notes, while the woman, Monterone’s daughter, is forcibly changed into the golden dress typical of the Duke’s playthings, in shame and despair. This was the opening of “Rigoletto” at the Teatro Real in Madrid, as envisioned by director Miguel del Arco. His interpretation of the narrative revolved around the women, their struggle in a world dominated by powerful, corrupt men using both money and violence as instruments of exploitation. Frequently, too frequently, the stage saw the presence of groups of female dancers engaging in suggestive, and at times outright vulgar, dance movements trying to cater to the court’s desires. In the last act, desperate prostitutes toil in the proximity of Sparafucile’s tavern, portraying mime-like depictions of sexual acts or trailing clients while dragging high platform shoes, reminiscent of soulless zombies.

This approach shifted the focus away from Rigoletto and his internal conflicts. The original plot, and the score, delve into the complexity of Rigoletto’s character. He emerges as both an accomplice to the Duke and his courtesans and their victim, simultaneously embodying a ruthless enabler of despicable crimes and a loving, tender father. At the narrative’s core lies the ominous curse: Monterone, a desperate father, curses Rigoletto, who callously mocks him for attempting to defend his daughter’s honor. This curse becomes the catalyst for Rigoletto’s downfall as a father, leading to the ruin and death of his beloved daughter. In this production, he seemed reduced to merely “one of the pack” – an embittered, evil soul orchestrating the Duke’s crimes, derisively mocking and laughing at the expense of the victims. Verdi famously declared Rigoletto “a Shakesperean character”; this quality was hard to recognize in del Arco’s view.

A Superb Cast

Still, Rigoletto remains one of the most compelling paternal figures created by Verdi, who gave this despicable wretch some of his finest music, and Ludovic Tézier stands out as one of the foremost interpreters of this role nowadays. His baritone was warm and velvety, expressing a true Verdian quality. His heavenly legato rests on an extraordinary lung capacity: he is capable of effortlessly spinning never-ending phrases, which he shapes with intelligence and elegance. He has a natural nobility in his voice and countenance, which, in the first act, did clash a bit with the character. During the feast at the Duke’s palace, Rigoletto was dressed in a corset and a plumed headpiece (costumes by Ana Garay), jumping around and mocking everybody; seeing Tézier in this situation was a bit like seeing Giorgio Germont getting drunk at a party. However, he was much more attuned to the character during the duets with Gilda, which were moving and emotionally charged. His “Cortigiani” was absolutely masterful, his baritone turning dark and booming during the invective, only to melt into sadness and sweetness when he is reduced to begging the courtesans to return his daughter to him. He sang all the unwritten high notes “of the tradition”, which is often frowned upon, these days, but, with such a performance, we would have forgiven him anything.

The stage at Teatro Real was nearly bare, thanks to the clever set design by Sven Jonke and Ivanna Jonke. They opted for large sheets of red or black fabric that shaped into hills and mounds, morphing and shifting to often give an ominous vibe. Gilda was literally encased in a bubble, surrounded by tropical greenery and trickling water—a visual nod to her father’s desperate attempt to shield her from the harsh world, creating a little oasis of innocence for her. Adela Zaharia, portraying Gilda, was a revelation — a singer one might not have experienced live before. She left a lasting impression with her truly lyrical soprano, effortlessly delivering rounded high (and super-high!) notes without any discernible signs of passaggio, and a light, agile quality. Zaharia exhibited an impressive command of bel canto technique, showcasing exquisite phrasing throughout. Her rendition of “Caro nome” was exceptional; tackling an aria so widely known, Zaharia skillfully avoided rushing through it, instead breathing life into the portrayal of a young teenager navigating love and hormonal storms for the first time. Each high note and ornamentation carried meaning, contributing to the nuanced portrayal of the character’s emotional turmoil. The idea was supported by the scene: Zaharia sang against a wall of greenery, while the hands, and then the bodies of several naked dancers emerged from the green wall and floor enticing her, representing her first discovery of sensuality. The idea may not have been original, but it was very well executed.

Javier Camarena was in great form; while some might argue that the role of the Duke of Mantua is too heavy for him, his performance on the opening night of this production proved his voice to be an impeccable match for the character. His tenor was brilliant, his high notes like laser beams, while his natural enthusiasm breathed life into a virile, powerful, and confident Duke. Camarena managed to balance elegance – especially in the closing of his phrases – with a rowdy, exuberant energy, one may never understand how he does that. The love duet with Zaharia was one of the highlights of the performance, their styles perfectly matching, their timbres complementing each other with great chemistry. They both raced to the high C sharp together for an exciting finale.

The direction made him more despicable than ever, his arrogance filling the stage. In his final scene, in Sparafucile’s tavern, the Duke was portrayed as drunk, wobbling from chair to chair, singing “La donna è mobile” gripping a bottle of wine. This portrayal stirred some teeth-gnashing in the theater, but “La donna è mobile” is indeed a drunkard’s anthem, and Camarena delivered the performance with all the accents and the details written in the score, with perfect phrasing, all while reeling and stumbling, hugging every customer.

(Credit: Javier del Real)

A Controversial Production

In my view, the overall impact of the production was positive, and I am clearly in a minority, given the boos that welcomed the production team at curtain call. Sure, there were moments when the sexual innuendos got a bit overwhelming, and the constant specter of sexual assault became a tad exhausting, but I reckon that was precisely the point. Miguel del Arco painted a picture of a world where many women have had to, and still do, navigate around the threat of male violence. Besides, in truth, it’s not entirely out of place in this opera, where women are constantly preyed upon. The one thing I will not forgive is the dancers during “Sì vendetta.” The scene was cleverly prepared, with Rigoletto experiencing hallucinations of the encounter with Monterone, perceiving the Duke before him. His response was a burst of manic delight at the prospect of revenge, with Tézier’s voice taking on an almost frenzied intensity. His duet with Zaharia was superb, but the fretful dancer’s movements were just distracting.

Conductor Nicola Luisotti led the Orchestra of the Teatro Real in a beautiful reading of the score. The sound was at times reduced to a whisper, with a chamber ensemble quality, especially during the most poignant parts, only to explode with true Verdian vigor. Luisotti clearly loves and understand this music, and the orchestra followed him in a very convincing performance.

Simon Lim sang Sparafucile with a solid bass and an appropriately menacing attitude, while Marina Viotti was a very convincing Maddalena, her bronzed, mellow mezzo perfectly supporting the quartet “Bella figlia dell’amore.”

In the last scene, Gilda’s death, both Tézier and Zaharia elevated the emotional intensity, delivering a duet that melted hearts, resonating with palpable desperation in the father’s voice. At the end, a group of naked female dancers entered the stage, perhaps angels, welcoming Gilda into their midst as the last victim of a harsh world for women. Rigoletto remained on his knees, alone in his desperation. It was a powerful and emotional ending.