Teatro Real de Madrid 2022-23 Review: Il Turco in Italia

By Mauricio VillaThe Spanish opera coliseum presented a new production of Rossini’s opera buffa, “Il turco in Italia,” signed by Laurent Pelly. There were two different casts and three different sopranos for the leading role, performing in the ten performances planned. But superstar Lisette Oropesa, was sick and had to cancel opening night. In this case, the fantastic Spanish soprano, Sara Blanch, stepped in from cast B and sang opening night with first cast.

No Disappointment at All

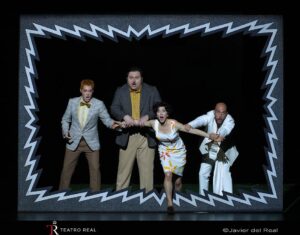

There was no disappointment at all, to those who know the exquisite and hilarious work of the stage director Laurent Pelly. But people who were new to this director’s style, found a frenzied performance, where everybody danced, both soloist and choir. It was non-stop and paired with an extremely dynamic staging to perfectly match Rossini’s lively music. Pelly, who is one of the most prolific directors today, and who is especially known by his comical productions, knows how to take the acting and movements to the extreme without it being an overacted farse. The composition of the characters is believable and funny at the same time. He succeeds in comical works because he has found a way to do comedy as a combination of funny, dynamic, and full of dancing. He refuses any cliches. Instead, he fulfills the characters and their relationships with truth and emotion.

In this, he proposed an unhappily married woman, Fiorilla, who is obsessed with photo novels and constantly reads them to escape from the boredom of her marriage. It is out of the pages of one of these photo novels where the Turk emerges, turning the opera into a constant game between reality and the imaginative world of the melodramatic novel. The characters keep coming in and out of empty comic strips. The imaginative sets of Chantal Thomas are full of gigantic pages of photo novels and the houses of Don Geronio and the poet. Everything is painted flat and has a 2D imitating comic drawing, except for the elements like stairs, doors and windows which are used in the different actions of the staging.

Star-Studded Cast

Sara Blanch, who portrayed the leading soprano role, has a sweet Lirico leggera instrument with a velvety quality in the centre and middle register which turns out bright and sonorous in the higher range. Her opening aria, “Non si da follia Maggiore,” was expressive with depurated coloratura for the multiple roulades and subtle variations on the repetitions up to high B natural. Her voice seemed to fly effortlessly and freely through this difficult Rossini piece which keeps the voice moving constantly. Although this is a good exercise to warm up the voice on the stage, Rossini might have been thoughtful and conscious about the length of this role and the stamina that is needed for the soprano who sings about three quarters of the whole opera. The tessitura is generally quite central and does not go higher than A natural. But Blanch took advantage of the high tessitura and interpolated a beautiful cadenza when going up to a shining sweet high C in the duet, “Per piacere alla signora,” with Don Geronio.

She proved her dancing skills on the phrase, “con marito di tal fatta,” with a stylish moving of the hips and arms. She introduced a secure and sonorous high D on the musical bridge between the final repetition to conclude the duet. The highlight of her performance, for the deep emotion on the slow section and the showcase of vocal pyrotechnics in the cabaletta was her final aria, “Squalida veste.”

Italian bass-baritone Alex Expósito sang the title role. The nature of his voice fits perfectly with Rossini’s writing which demands a strong voice able to give vocal weight to the character, but flexible enough to sing the coloratura, which is constant throughout the score. Expósito sounded emotional and sweet at the same time. He sang the opening B natural of his first line, “Bella Italia,” with an astonishing crescendo, written in the score, from pianissimo to forte. He also sang his entrance aria with expansive long legato lines, including coloratura, and presented to the audience for the first time the sexy and exotic character that becomes the centre of the whole mess of the plot. His characterization was sensual and funny. He did not doubt about jumping, running or climbing as the staging demanded.

The duet with Don Geronio at the beginning of Act two, “D’un bell’uso di Turchia,” was the highlight of his performance. His perfect fast parlato singing with immaculate Italian diction and the interpolated high notes like the high F in “D’involarla,” or the sustained high F along Don Geronio at the end of the duet. His performance was funny and amusing without being clownish or overexaggerated.

Baritone Misha Kiria sang the role of Don Geronio. Kiria’s voice sounded dark and round, but he was agile and flexible throughout the fast parlatto moments of the score. He also made good use of his upper register, putting out a long-sustained F at the end of the first scene and even a high G after his first act duet with Fiorilla.

The baritone Florian Sempey sang as the poet Prosdocimo. It is a lyrical role with a high tessitura that demands phrasing around high F, F sharp and G. This means that the high register should sound easy and lyrical rather than heroic and bombastic, however, this is where the baritone fails. His high register sounded more optimal to Verdi compositions than to the score of the Pesaro composer. His tendency to include high notes which sounded bombastic and heroic seemed far from the Rossini style. His G sharp in “per che?” in the first act’s terzeto, and his A natural in an interpolated cadenza in the final ensemble on the line “Oh! Che chiasso avra,” resulted in an unnecessary demonstration of his high thunderous notes. Nevertheless, he is a good artist who sang agile and fast during the parlando moments, with depurated coloratura technique and deeply committed with Pelly’s demanding staging.

Edgardo Rocha sang the rarely performed cavatina, “Un vago sembiante.” This comes as an appendix on the critical edition from Ricordi of this score. He demonstrated his ability to sing fluently in a high tessitura. It is, as most roles in this score are, full of coloratura, scales and roulades that constantly navigate in the upper range, around high A flat and B flat. The tessitura of the first act’s quartet keeps the same high writing passing constantly through B flats. Rocha is able to sing the arduous tessitura, but his upper register sounds open and sometimes it sounds even strained. His passagio zone sounds too open and his voice decreases in volume as he rises in the tessitura, while his middle voice is well projected. Anyway, this is a very hard role because it has no dramatic weight in the plot, but all his interventions are always extremely high. His short arioso, “Per chem ai se son tradito,” is written mostly above the staff going up to B natural and high C.

But those high notes are passing notes in Rossini’s writing and therefore should sound easy and natural. This is where Rocha navigated dubiously. He can sing all the notes, but he still sounded open and his high C in “liberta, si,si, si,si,si, mi dona,” sounded pushed and tense. Bel-canto is above all beautiful singing, so any sign of effort and strain goes against the style. This demonstrates that good singing is not just about reaching the high notes but about how they sound, too. He bravely sang his second act aria, “Intesi: ah! Tutto intessi,” with its devilish coloratura and high tessitura. He interpolated a high C in the second “vendetta,” which again sounded too open and unstable. His coloratura was not too concise during the last section of the cabaletta, “per un offeso amante.”

Giacomo Sagripanti offered a critical edition of the score, which included the cavatina for Narciso and Geronio’s second act aria, but cut down Albazar’s aria, as it is believed that was not written by Rossini. He gave emphasis on the crescendos and frenzies of this piece by choosing a fast and lively tempi, but also finding a perfect communion between the interpreters and the orchestra. The orchestra sounded clear and Sagripanti reinforced Rossini’s timbrical richness by maintaining the purity of the score despite of the fast tempi. He played the fortepiano himself for the recitatives. The intervention of the orchestra and chorus of Teatro Real was brilliant.

Vibrant Return

Oropesa resumed the performances of “Il turco in Italia” on the 4th of June after cancelling her premiere. The soprano recovered completely, and her voice sounded bright, with harmonics and in top shape. Her warm velvety sound has grown and possesses more projection without compromising the high register as all her beautiful and stylish variations on the repetitions insisted in the higher range of her voice, including fast scales, staccato and mezza voice high notes.

She offered a fresh interpretation of her entrance aria, “Non si dá follia maggiore,” a funny amusing duet with the Turk. ”Bella Italia” has two ringing high C’s in the first act quartet and a funny amusing duet with Geronio, “Per piacere a la signora.” In fact, this duet and her final aria, “Squalida veste,” were the highlight of her performance. She had to take a bow after both pieces returning to the stage as both ended with Fiorilla leaving the stage, due to the warm insistence of the audience. Her portrayal was focused on big and funny gestures, measuring or cutting down the dancing or physical demands of Pelly’s staging. She received a warm ovation at her curtain call.

A funny, amusing and frenzy production trademark of stage director Laurent Pelly, with a strong cast and the stylish interpretation of the conductor Giacomo Sagripanti.