Teatro Real de Madrid 2019-20 Review: Don Carlo

Sergio Escobar, Ekaterina Semenchuk, Maria Agresta Lead A Wondrous Cast In Verdi’s ‘Magnus Opus’

By Mauricio Villa(Credit: Javier del Real)

The Teatro Real opened its season on the Sept. 18, 2019 with Verdi’s “Don Carlo,” an opera inspired in the old monarchy of Spain. Present at the big event were the King and Queen of Spain, as well as famous figures from the world of politics and arts.

“Don Carlo” is a massive endeavor for any theater, requiring not just the best four singers in the world (as is the case for “Il Trovatore,” per Caruso), but six. The endeavor of this particular production must have been immense for the Teatro Real, as it presented three casts, including four tenors to cover for Francesco Meli, who fell ill during the rehearsal process and subsequently canceled his appearances.

Brilliant Production Without Its Heart & Soul

The production on offer came from the Frankfurt Opera in 2007, with direction by the stylish modern director David McVicar. He chose a modern conceptual set, created by Robert Jones, and period costumes by Brigitte Reiffenstuel. Lately the famed director has been using period sets and costumes, proving that you can do good theatre in a more traditional style.

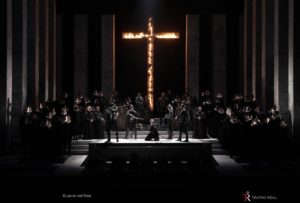

Since this production comes from the Frankfurt Opera where modern interpretations are in vogue, McVicar chose a neutral square space surrounded by brick white pillars and some rectangular modules with a black platform that rises several levels. If you watch the performance from upper levels of the theatre they look like coffins and when raised up to the highest position, you could feel like you are watching the Holocaust memorial in Berlin. The white bricks produce a big contrast with the black and dark costumes; even the silvery armor or golden costumes from the kings are darkened. It is a claustrophobic set which reminds one of a big prison. There are few elements and props, such as a hanging incense burner for the scenes which take place inside the monastery. A big cross lowers for the big scene of Act three and it eventually turns into flames as a metaphor of burning the heretics.

Unfortunately that level of intricacy did not quite translate with the directing of the actors themselves. McVicar reportedly did not come to supervise the production and his absence was quite noticeable. Entire scenes where dramatically empty with the singers moving from one point to another as marked but with no motivation or connection between them. From seeing other McVicar-directed performances, there is no way that he would not have left arias or scenes with the singers feel totally lost and turning to stock gestures. It was disappointing to see a specifically created production and concept reduced to generalized execution. One imagines that revival director Axel Weidauer did his best to reproduce the original staging the best he could, but clearly McVicar’s touch was the missing ingredient to make this production soar.

Making It Count

Spanish tenor Sergio Escobar portrayed the title role for one single performance on October 3 in what was his company debut. He did not have much rehearsal time, so his effort was that much more impressive as he proved himself a courageous artist with a great voice. It was admirable to see how he had absorbed the stage directing and did his utmost to interact with his colleagues in every scene; there was nothing in his performance that would tell an audience that this was his first and only showcase.

He has a lyrical voice, tending toward lyrical-spinto, that is potent, with a solid low and medium register and thrillingly secure high notes: in essence, he has the ideal voice to sing this character. The role of Don Carlo is not only long in the five-act version, but demands that the tenor be comfortable in the passaggio that must often ride over some heavier Verdi. Escobar began the performance with a colored and shadowed recitative: “Fontainebleau, foresta immensa” before delivering a rotund “Io la vidi” where he demonstrated his vocal line, flexibility and the first of the many high B naturals (this role has an insane insistency on the high B flat, and many B naturals). It is frighteningly difficult open the opera with an aria when you haven’t had the chance to warm up properly on the stage. The followed duet with Elisabetta maintains this high tessitura within the long famous Verdi legato phrases, and Escobar demonstrated admirable technique, instrument and stamina. Even when the chorus entered at the end of the scene, you could still hear Escobar’s voice rising over the orchestra and chorus with forte sound.

During “Dio che nell’alma infondere,” Escobar and baritone Luca Salsi blended their voices in excellent unison. Escobar managed to deliver the line “El la sua fe, io l’ho perduta” with an effortlessly high B natural on the “i” vowel; many tenors usually changed to an open vowel like “a” or “e” because is more easier to hit the high notes with the open vowels rather than the closed “i”).

The duet with Elisabetta in the next scene was moving and thrilling, with the tenor attacking several high A naturals and B flats while sustaining the emotional tension and potrtraying the mental decline of Don Carlo and his obsessive love with his “mother.” He kept this standard for the whole performance, his voice perfectly audible during the trio in Act three (and you need to have a big and voice projection not to be overpowered by Ekaterina Semenchuk’s voice) and the great ensemble number at the end of the act where he has the most exposed high B natural in “il tuo salvator,” here executed with ardour and menace.

He managed to keep his voice fresh for his last duet with Elisabetta in Act five where the vocal writing lives in the higher register, going constantly to high A natural and emitting a soaring high B natural in mezza voce on his las line “Per sempre addio.” He received a deserved ovation during the curtain calls.

Two Heroic Turns

Soprano Maria Agresta took on the role of Elisabetta. She had tremendous success here with “Il Trovatore” in July and did the same with “Don Carlo.” From her first entrance in Act one duet, Agresta proved that she had the role, as her middle register is dark and sonorous with potent high notes; her piannissimi and mezza-voce are also breathtaking. She showed very wise control of her voice, particularly on the two B naturals on “Oh ciel” during her duet with Don Carlo. She demonstrated a similar strength in her sustenance of long mezza-voce phrases in “Non pianger mia compagna;” here she managed a soft whisper from the initial low C to high B flat during the whole fragment.

Her voice and projection were also big enough to cut through the orchestra and chorus during the big concertante scene at the end of Act three. She went back to the soaring piannissimi in “Ah! sola, straniera,” delivering gentle High B flats and sustaining long phrases in a single breath.

But her big moment comes at the end of the opera in Act five with her aria “Tu che la vanita.” After a long night of singing, ending on a massive aria is a massive endeavor, specially a passage with continuous descents to low C even a low A, with big contrasts between forte and pianissimi lines and high notes. But Agresta was more than up to the task singing with dramatic passion throughout. The very last note sung in the opera is a high B natural that Elisabetta emits on “Oh ciel,” and Agresta gave all she had left.

Mezzo-soprano Ekaterina Semenchuk, a favorite of Teatro Real, has sung three consecutive Verdi roles: Amneris (2018), Azucena (2019) and, now, Eboli (2019). With her round, dark and velvet mezzo soprano voice, she interpreted the Princess wonderfully, scoring another vibrant success.

Her first appearance in second scene of Act two saw Semenchuk lighten her voice to what almost sounded like a soprano timbre; this enabled her to master all the coloratura and staccato notes that Verdi wrote for this first aria. It is a tricky passage written mostly in the middle register, but with coloratura that ascends repeated to high A naturals which must sound easy and light. Semenchuk managed wonderfully throughout.

The tessitura of the trio ranges from low B flat to high B natural, and it was here that Semenchuk showed off her potent low chest notes on “Al mio furor sfuggite invano il suo destin,” her strong central register on “Trema perte falso figliuolo,” and her potent high range with a thunderous high B.

But her big moment comes in Act four where she reveals her betrayal of the queen and sings her big aria. Throughout the quartet and subsequent scene with the Queen, Semenchuk used all her dramatic resources, coloring every phrase and emphasizing the low notes (this section is really central and low, from high G to low B flat) on such passages as “io stessa avea commesso,” which she ended with a resonant low C. When you heard such insistency in the lower register, you started to question how she might manage the higher tessitura and longer legato phrases of “O don fatale.” But Semenchuk’s control of her voice is so impressive that she switched from her lower register to her higher one without compromising the quality of the sound.

“O don Fatale” begins with an outburst of remorse and fury with Semenchuk giving all of her potent sound and dramatical input that she coronated with a flawless and powerful high C flat. Then the mood of the aria changes, becoming melancholic and sad. Here the mezzo’s voice sobbed on “O mia regina,” delivering the passage with long phrases and a high B flat that she produced effortlessly. At the close of the aria, Eboli resolves to save Carlo, the music shifting to a more heroic pose. Here, Semenchuk’s voice thundered through the hall and she climaxed with two faultless high B flats, bringing down the house.

(Credit: Javier del Real)

Heroic Lows

Luca Salsi portrayed the role of Rodrigo, Don Carlo’s best friend. Salsi was last heard at Teatro Real in “Rigoletto (2015)” and his voice has gained more depth and volume, keeping his vocal line and easy high notes intact while becoming even more of a Verdi baritone.

Even if his sound was not overly voluminous, Salsi’s voice managed to project so perfectly that you could feel like he was singing beside your ears. He was impetuous and heroic in his entrance duet with Carlo, “Dio che nell’alma infondere,” where his tessitura is always around high F, an uncomfortable zone for a baritone to sing. However, Salsi showed no problems in managing the vocal line and coronated the passage with a splendid high G.

The second scene of Act two is probably the most lyrical section for Rodrigo with his “Carlo, ch’è il sol nostro amore.” Here Salsi showed his flexible dark voice in mezza voce, with crescendos and easy high F sharps. In the confrontation with the King Felipe II, he showed all his rage and determination in the way he sang “Orrenda, orrenda pace! La pace è dei sepolcri!” Also moving was “Sospettti tu di me?” at the end of the terzetto, sung with a pleading piannissimo soud that proved to be more effective than the forte usually employed; it expressed the confusion and shock of Rodrigo in this moment.

During Rodrigo’s big scene at the end of the opera, Salsi delivered emotionally convincing portraysl of “Per me giunto è il di supremo…O Carlo ascolta.”

Russian bass Dimitry Belosselsky took on the role of Filippo II. He has a basso-profundo voice with a cavernous sound throughout his whole range. This opera requires the singer to go from the extremes or a high F sharp to a low F, more than two octaves overall. Belosselsky voice was ideal for the role, showing authority and determination and keeping a fluid vocal line during his aria “Ella giammai m’amo.” There were some difficulties in the section “A me desse il poter di legger nei cor che Dio può sol veder,” where Verdi wrote a slightly florid phrase. However, it is unfair to demand a heavy voice to be agile in scales. Nonetheless, the interpretation of this aria was melancholic and heavy-hearted. The duet with the inquisitor was thrilling and tense and the Russian bass managed to deliver some potency on his phrase: “Dunque il trono piegar dovrà sempre all’altare” which goes from high F to low F. He coronated his performance with the strong high F sharp on the final“Mio padre.” His stage presence and his complexity was ideal for the role as well.

To finish the sextet of important voices of this opera was bass Mika Kares in the infamous short role of the Inquisitor. It is a difficult role to sing as you basically have to go on stage after two hours of the performance to sing your only big moment – a duet with Felipe II in Act four. The tessitura goes from several high Fs to a low E, which is undeniably low for the bass. Unfortunately, the role proved to be too heavy for Kares, who was fine with the high Fs, but could not be heard on his low E; he paled singing next to Belosselsky’s big voice. The bigger issue is that the Inquisitor should be far more present than Filippo is the dynamics of the scene are to be believed. Fortunately, Kares solved his lack of vocal power with an amazing personification of the old, blind priest.

Also notable was the brief appearance of Leonor Bonilla as “the voice from heaven.” She delivered a sweet coloratura timbre and soaring high B naturals that sounded angelic.

The chorus of the Teatro Real was ever-present from beginning to end and gave a strong powerful performance of “Spuntato ecco il di,” a scene that features a structure similar to the “Triumphal March” from “Aida.” It is essential to point out that the chorus sounded better than ever.

The same must be said for the orchestra, which is undeniably attributed to the maestro’s potency.

Nicola Luisotti, the principal guest conductor of Teatro Real, has a bright energy which he transmits to the musicians at the pit. He maintained a balanced sound between the string and brass section, sometimes reinforcing one over the other to maintain the tension and reach the climax in a big unison forte. I have to congratulate the soloist who played the celo on the introduction to Felipe’s aria, “Ella giammai mamo,” as the interpretation was extremely moving and full of pain. It has been said that “It took Wagner a whole tetralogy to talk about the human solitude when Verdi manages to do it in a cello solo of three minutes.” This performance, in particular, lived up to the power of that quote.

This was a fantastic “Don Carlo,” especially from a musical perspective.