Teatro Nacional de São Carlos 2021-22 Review: La Clemenza di Tito

Brilliant Musical Interpretations Make Case for Staged ‘Clemenza’ Over Production

By Ching ChangOpera performances resumed at the Teatro Nacional de São Carlos in Lisbon earlier this year as Portugal’s handling of the pandemic was widely praised as possibly the best within the European Union. In Lisbon, ensembles large and small have begun filling up local church series, community performance spaces, and neighborhood stages, while fado singers have returned to smokey late-night bars and restaurants. While the new variant has now put officials on alert, improved conditions had made it possible for a vibrant concert life to return to the cities.

To be sure, this only happened because of the population’s high compliance with mask mandates and judicious acceptance of public health guidance (helped by remarkably low levels of recalcitrancy against vaccination), but it was also a function of the relief subsidies many artists received during the period of isolation. The smaller arts groups proved to be extremely agile and adaptable and quickly started populating the concert calendars, eager to show their work and prove to taxpayers and the state that they weren’t just sitting idly on public monies during the pandemic, and thus are deserving of renewed support in the future.

The Teatro Nacional de São Carlos, however, is a whole different institutional creature within this artistic ecosystem. Facing unique challenges that are tough to overcome even during normal periods, the pandemic greatly intensified the institutional tests the venerable opera house had to meet. Though not without some bruises, the Teatro São Carlos rose to this challenge, for the most part, ending its pandemic season this week with three performances of Mozart’s “La Clemenza di Tito,” led by music director designate Antonio Pirolli, and featuring an international cast consisting of Pablo Bemsch (Tito), Ruxandra Donose (Sesto), Susana Gaspar (Vitellia), Cecilia Rodrigues (Servilia), Miriam Albano (Annio) and José Corvelo (Publio).

Though “Clemenza” is a fine example of Mozart’s mature style, this opera was composed under commission for the coronation of Leopold II of Bohemia in Prague, and is largely a piece of monarchist propaganda: it generously portrays a benevolent emperor Titus, torn between personal loyalties and the tough decisions instigated by an assortment of stakeholders under ever-changing circumstances. To be sure, Portugal abolished its monarchy in 1910 and became a republic, but still, it seems like a fitting work to present at the end of this year at the São Carlos, where artistic director Elisabete Matos had to face some formidable and difficult choices while attempting to present some semblance of an opera season, planned entirely during the fluid and shifting priorities of a chaotic pandemic environment.

Difficult Choices & Mixed Bags

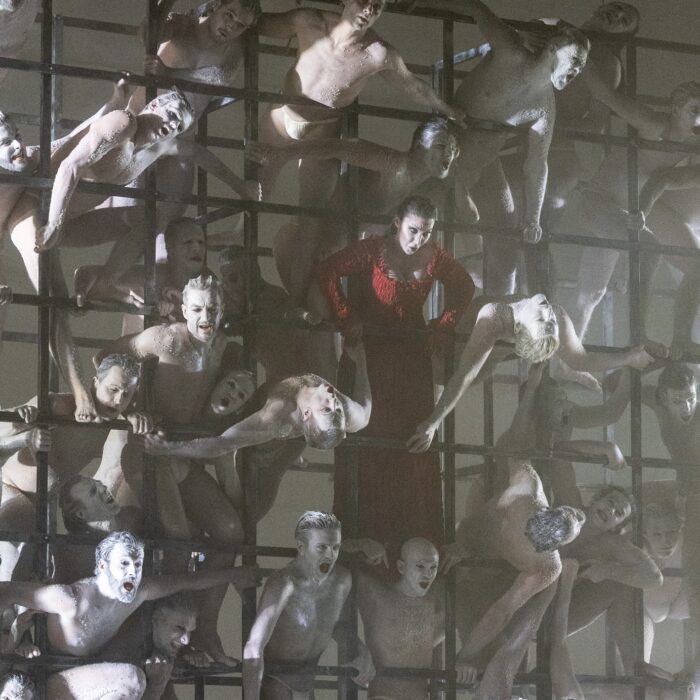

Chief among the challenges was the necessity of compliance with public health mandates, not only for the audiences (where capacity controls were imposed) but also the safety regulations for artists and staff, imposed by both the municipality and labor unions. While the São Carlos’ splendid opera house is a gorgeous, grand yet intimate jewel box of theater (with just over 1100 seats in the Italian palcoscenico format), it also has a relatively small orchestra pit, making compliance with workspace distancing rules all but impossible to achieve within the confines of the orchestra pit. Right from the outset, the decision was made that the orchestra would play on the main stage for the year, and similarly, the choir had to be properly distanced as well, so a grid of scaffolded paneled partitions was built around the back perimeter of the stage, from where each choir singers would perform, contained in relative isolation. Other less obvious adaptations were made as well, and the result was that there was precious little space left on stage to execute any theatrical action; so the operas this past year were presented entirely in a semi-staged concert fashion, with scenic props used sparingly.

As to be expected, the results of these experiments were a mixed bag, with some productions more satisfying than others, and by necessity relying predominantly on the effectiveness of the bare human element. Earlier this year, the performances of Verdi’s “Ernani” proved to be highly successful, showcasing a cast of world-class, seasoned veterans headed by American tenor Gregory Kunde in excellent form; the fine Chinese soprano Hui He as Elvira; and a pair of superb Italian baritones in Simone Piazzola (as Carlo) and bass Fabrizio Beggi (Ruy), also under the direction by Antonio Pirolli. Later in the season, audiences were presented a finely sung reading of Tchaikovsky’s “Iolanta;” and last month it showcased Handel’s “Ariodante,” a production in which the theater made a credible attempt at employing a minimalist designed scenic element on stage.

The performances this past week showed that, in many ways, “Clemenza” is an ideal opera to be offered in concert staging, since the action is quite static for the most part, and the talky feel is further intensified by the numerous recitativo sequences. Unless a production is going to introduce very original perspectives (as in Peter Sellars’s and Teodor Currentzis’ version of the opera staged at the 2017 Salzburg Festival), one finds few compelling reasons why a theater should invest in a new traditional stage production of this opera, when the predominant artistic value has to be the musical one.

But the Music…

As such, there were many compelling musical moments at this past week’s performances at the São Carlos, but also some that were marked by unevenness, both vocal and interpretive. As Tito, Argentinian tenor Pablo Bemsch had obvious lyrical qualities, displaying agility and vocal purpose in the Act two bravura aria “Se all l’impero, amici dei,” but otherwise his depiction of the character often lacked the nuanced contrast of Titus’ vulnerable humanity juxtaposed against the stance of imperial grandezza.

A veteran at performing on international stages, mezzo-soprano Ruxandra Donose–for many years a favorite artist at the San Francisco Opera–offered her warm and agile singing as Sesto, shining with poignant commitment among the leads in the cast. In Sesto’s great “Parto, parto,” the bravura aria was greatly enhanced by the superb contribution of clarinetist Joaquim Ribeiro’s fluid instrumental obbligati. The much-beloved Portuguese soprano Susana Gaspar, trained in Lisbon before becoming a resident young artist at the Royal Opera House at Covent Garden, had a more difficult night controlling her instrument in Act one, much as her character Vitellia loses control of the situation later in the plot. She did manage to shine in Act two, producing a tenderly shaped rendition of the rondo “Non più di fiori.”

Above all, these performances offered a textbook case of artists in supporting roles outshining the leading cast in excellence. Italian mezzo Miriam Albano, a house artist at the Vienna State Opera, sang a superb account as Annio, with richly warm-toned singing and exquisitely shaped phrasing. The young Portuguese soprano Cecilia Rodrigues sang a charming Servilia, with her luminous delivery of the captivating aria “S’altro che lagrime” a definition of Mozartian elegance. The veteran Azorean bass José Corvelo served a seamless and resounding bass voice in his assignment as Publio.

Italian conductor Antonio Pirolli led a brilliant and crisp reading of Mozart’s score with the Orquestra Sinfónica Portuguesa, showing the São Carlos distinguished partnering ensemble’s refined fluency with Mozartian style. With the announced resignation of maestro Joana Carneiro earlier this year, Pirolli is expected to formally assume the post of Music Director of the orchestra next year.