Teatro La Fenice 2019-20 Review: Don Carlo

Robert Carsen’s Production Impresses & Disappoints In Equal Measure

By Alan Neilson(Photo: Michele Crosera)

Rodrigo has been killed by an assassin’s bullet and lies dead on the floor. Don Carlo accuses the King of his murder, and the mob breaks into the prison to demand his release. Filippo’s hold on the throne is hanging by a thread, as he struggles to quell the rebellion. The Grand Inquisitor arrives to restore order, bringing Act three to a close. Up to this point the narrative had been true to the libretto. However, Robert Carsen, the director of La Fenice’s new production of “Don Carlo” had other ideas. As the cast leaves the stage, Rodrigo jumps up and embraces the Grand Inquisitor. All is not what it seems to be; there is conspiracy in the air.

Rewriting The Libretto

Act four begins as expected with Elisabetta and Carlo’s farewell, as he prepares to depart for Flanders. The King appears along with the Grand Inquisitor, who demands Carlo be handed over to the Inquisition. Again everything as it should be, and then we moved into the end game, in which events took an unusual turn: Carlo is shot dead by the Inquisitor’s assassin, followed by the King. Rodrigo then reappears, who is installed as the new King by the Grand Inquisitor.

Clearly, this is not the work envisaged by Verdi and his librettists, Joseph Méry and Camille Du Locle, in any of its many versions, including the four act Milan version in Italian, which was used for this production. It is one thing to tweek an ending so that a character lives instead of dies or vice-versa, it is of a different order when wholesale changes are made, including to characterization.

Carsen’s approach was to examine the psychological complexities of the characters, which on the whole was very successful. It was his treatment of Rodrigo, however, which proved to be controversial. Rodrigo knows, and is friendly with, all the players in the drama, and is trusted by everyone. In other words, he could be seen as a manipulator on the lookout for opportunities to promote himself, a person who would willingly betray friends, and involve himself in a conspiracy to secure the throne. His behavior, which can be perceived as contradictory, makes sense within the context envisaged by Carsen. After swearing eternal friendship to Carlo, he is quick to lend his support to the King against Carlo’s interests, and disarms him when he draws his sword against the King, yet he eventually sacrifices his life for Carlo and Flanders. There is nothing inconsistent here, his death is fake and everything can be seen as part of his plan to steal the throne. Unfortunately, this is not what Verdi is telling us; there is no hint of Rodrigo’s duplicitous nature in the music, in fact, it is quite the opposite, the bond between Carlo and Rodrigo is emphatically genuine. This is, therefore, a “Don Carlo” in which the director has decided to dispense with the work as it stands and to rewrite it in a fashion which he believes to be more appealing.

Despite this, however, Carsen’s presentation was dramatically tight, powerful and insightful, which kept the audience absorbed. It possessed depth and drive, and Carsen’s changes certainly kept everyone guessing. Also, although purists may disagree, Carsen’s reading remained true to the underlying drivers of the drama and to many of the themes which Verdi was exploring, so in this sense it was a valid interpretation, if not of the narrative, or of Rodrigo’s characterization.

Carsen’s direction successfully opened up the power dynamics, which lie at the heart of the work, for all to see. There is no ambiguity in the Grand Inquisitors position, he is the power, which he uses to secure his position and that of the Church. The King is king only because he wishes it so, and he has the power to remove him, without the need of the rule of law to bring it about. The autodafé scene is cleverly conceived so that its focus is not on the ritual of burning heretics, but on the suppression of ideas, and the power to determine people’s thoughts. The heretics from Flanders are dressed as Protestant vicars, and are shot, not burnt; the burning is reserved for their books, their ideas, which must be visibly destroyed.

He was also successful in managing the series of complex relationships which exist between the characters and the inner conflicts which assail them. The triangular and complex relationship between Elisabetta, Carlo and Eboli were expertly handled, so that the various emotions associated with deep and genuine love, which are destined never to find fulfillment, are brought to the fore. The strained relationships between Carlo, Filippo and Elisabetta, which are centered on the conflict between love and duty, were also highlighted skillfully. Of course, the relationship between Rodrigo and Carlo becomes somewhat problematic, as the whole thing is now a charade, undermining Verdi’s examination of the bond of male friendship.

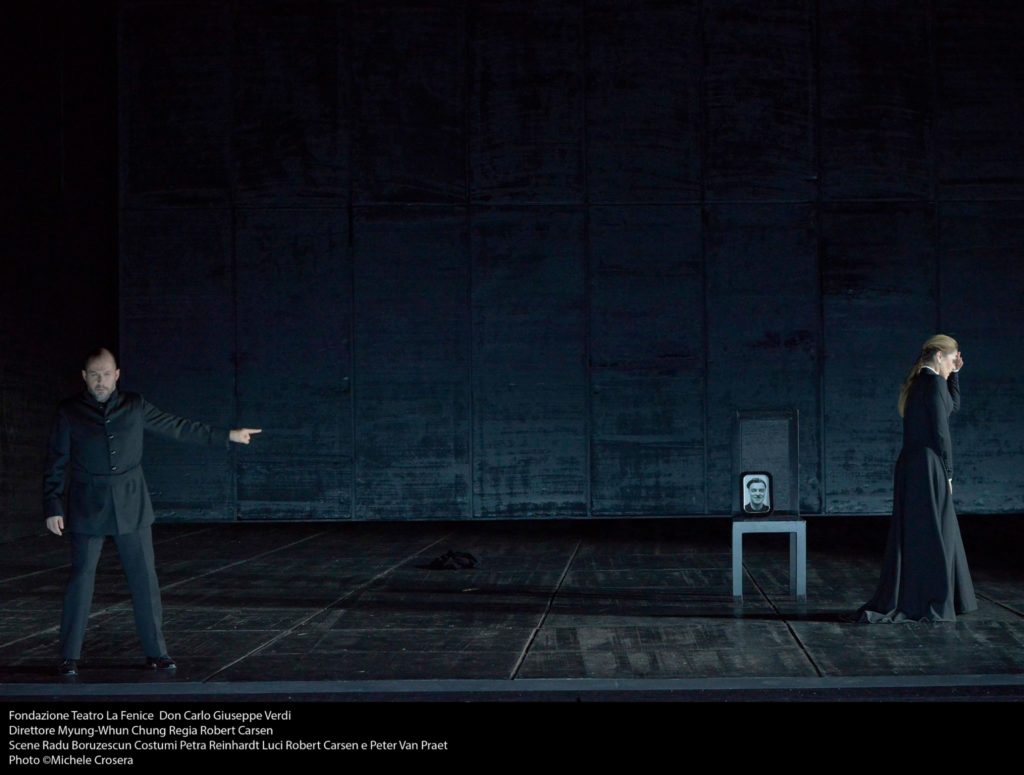

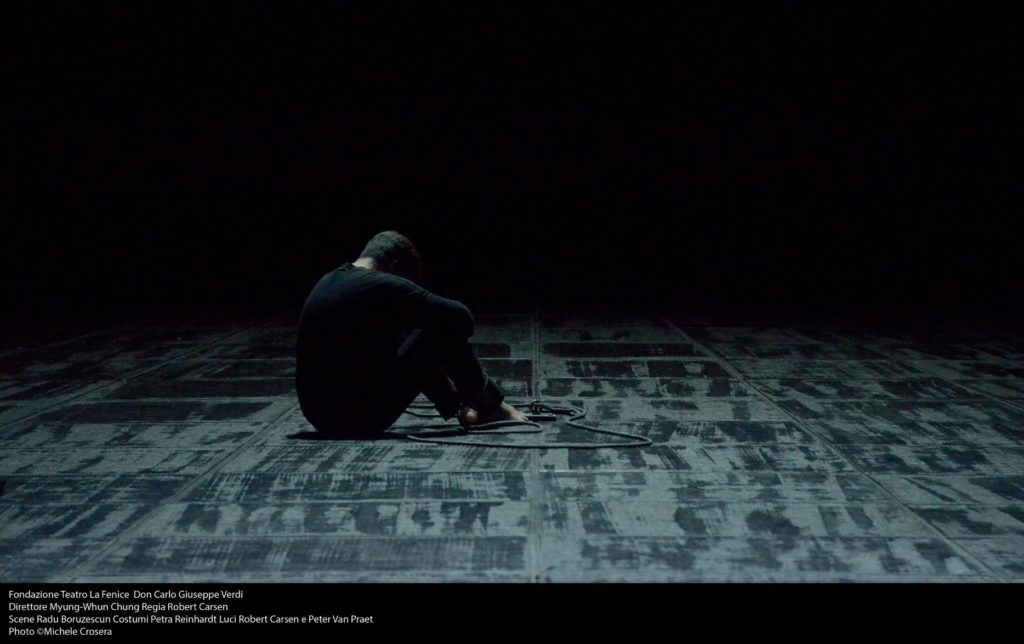

The staging was brilliantly designed to keep the focus on the individuals, to expose their underlying psychology and to provide a context in which the omnipresent state of oppression which hangs over the drama was magnified. The set, designed by Rada Boruzescu, was shorn of all non-essential items; often the singers were alone on the stage without any props at all. The defining color was black: black walls, black floor, black arches, black table, everything was black. There were doors and arches which opened up at the sides and back, on two levels, otherwise the stage was an empty, dark, cavernous space. The lighting, designed by Carsen and Peter Van Praet, was used to accentuate the effect. For large parts it was fairly subdued, but the occasional use of bright white light was used to pick out individuals, which not only focused the attention, but also helped to isolate them from the crowd. Likewise, the costumes, designed by Petra Reinhardt, were all black. They were modern, but not at all flamboyant. Religious figures were dressed in religious robes, women in long, plain dresses and men in casual attire or, in the case of the King, a formal stiff collarless suit.

It all came together superbly, in what was a highly stylized, pleasing presentation, which played no small part in enabling Carsen to present the psychological drives which motivated the characters. The atmosphere was heavy, dark and bleak, in which unknown people occasionally watched from the shadows. There was no levity, nothing to lighten the sense of dark foreboding. It also allowed certain scenes to rise out of the gloom to create a powerful spectacle. The autodafè scene was fairly low-key with the exception of the King who was dressed in the magnificent splendor of his full regalia, which although dark, sparkled and created a dazzling scene, which kept the real power hidden from public view.

A Strong Cast

Myung-Whun Chung, the musical director, produced an atmospheric and dramatically sensitive reading, in which his control of the overarching musical structure was excellent. He ensured that the dramatic tensions were carefully controlled, so that the climaxes had a thrilling and powerful impact. To this end he was attentive to the balance within the orchestra, carefully drawing out the textures with the right degree of prominence, and creating strong dynamic contrasts. Very occasionally, however, the contrasts were to emphatic and crossed the line into bombast.

The singers all gave strong performances, and engaged fully with Carsen’s psychological vision of the work, ensuring that all the characters were nuanced, multi-faceted portrayals, which allowed for dramatic and powerful confrontations that could be clearly linked to both their conscious and unconscious drives.

The role of Filippo II was played by bass, Alex Esposito. His was an authoritative, yet thoughtful and reflective king, fully aware of his responsibilities, position and the tenuous hold he has on the throne; he is nervous in confronting the Grand Inquisitor. In what was a nice touch, he thrusts Rodrigo into the chair behind his desk so that he can understand the isolation of kingship, oblivious to the fact that is exactly what Rodrigo is seeking. Esposito’s singing was sufficiently commanding, tinged by with an intolerant air. Yet he is a troubled soul, which Esposito captured in his refined and versatile phrasing. At the beginning of Act three he sings of his unhappy marriage to Elisabetta, and the emptiness of power, coating his words with deep melancholia, in what was a very human portrayal. His voice also displayed strength and energy, the quality of the vocal line remaining firm and consistent as he moved into the higher register, or when singing with more power.

The soprano, Maria Agresta, produced a compelling portrait of a feisty, courageous Elisabetta, who struggles between her loyalty and duty to Filippo with her love for Carlo, a situation exacerbated by her conflicting relationship with Eboli, which rapidly turns from friendship into anger on discovering her double betrayal. It was a performance of high intensity and high emotions. Throughout, Agresta displayed excellent vocal control and versatility, developing her character through intelligently crafted phrasing, whilst adding depth through shading her voice with an array of soft colors and inflecting her words with well-positioned emphases. In a number of scenes, such as when Eboli confesses the wrongs she has inflicted upon her, or where she is accused by Filippo of betrayal, her emotions are pushed to the limits. However, she was equally capable of singing with greater delicacy, as in the Act four duet with Carlo, “Ma lassù ci vedremo,” in which the lovers say a last farewell, which was tenderly woven; crafting sensitively protracted lines, and displaying a beautiful legato, sung pianissimo, she was supported by Pretti’s equally fine singing, in what was one of the many high points of the performance.

The tenor, Piero Pretti, produced a complex picture of Don Carlo, in what was a sensitive reading. He was a passionate and virile prince, courageous and determined, yet there was also a fragility, a reflective side which acted as a counterbalance. On a number of occasions, he is seen alone gazing at a human skull, a reference to Shakespeare’s “Hamlet,” reflecting on the meaning of events. Pretti sang with confidence and ease, with passion and ardor. He has precise and clear articulation. The voice possesses a rich pallet of colors, with a particularly bright luminous upper register which contrasted beautifully with the dark atmosphere, and created a wonderful visual-aural chiaroscuro effect.

The Korean baritone, Julian Kim, was parted as Rodrigo and produced an excellent singing performance. He has a strong, well-supported singing voice, with an attractive timbre. His phrasing is secure and nuanced, full of subtle accents, which provided depth to his portrayal. Moreover, there is a fluency with which he crafts the vocal line; his singing lies easily on the ear and gives it a natural lyrical quality. Presented as a vicious and duplicitous manipulator, which is not reflected in the music or the libretto, meant that it was difficult to make any sense of the character, other than what Carsen says he is. Up to the point of his “murder,” he is the Rodrigo one would expect, that is a loyal and trusted friend, who under intense political and religious pressure, wavers, but eventually comes through. After his resurrection, one has to reassess him, but assess what? This interpretation is simply not grounded in the music, and apart from one or two actions that hint at his emotional distance, for example, in the duet “Dio, che nell’anima infondere,” in which Rodrigo and Carlo don’t immediately face each other, but walk straight towards the audience, there is nothing to support this view of Rodrigo.

Princess Eboli was played by mezzo-soprano, Veronica Simeoni. It was not a particularly attractive portrayal, highlighting the Princess’ desperation and vindictiveness. However, Carsen’s also made it clear that she was a victim of the whims, right or wrong, of the powerful; it is made very clear, for example that she was Filippo’s mistress. She can be banished to a convent or exile, her pleas of remorse can be ignored, she can be sacrificed, while Filippo walks free. Simeoni’s singing was open, clear and bright, displayed an attractive coloratura, and was able to produce long lines exhibiting excellent breath control. The Veil Song was delivered reasonably well, but was more notable for the splendid choreography of the women dressed in black, covered with dark veils. The aria, “O don fatale, o don crudel,” in which she rages against her beauty and repents of her behavior, was more successful, in which her heartfelt remorse was acutely rendered.

The Grand Inquisitor, was played by bass Marco Spotti, in what was a solid, although not an outstanding performance. He has a dark resonant voice, but it lacked the necessary force to inspire fear or automatic subservience.

The Romanian bass, Leonard Bernad, was parted as Il Frate. He has an attractive middle register, and the lower register has substance, but there was a notable weakness in the upper register, which detracted from the overall performance.

The chorus, under the guidance of Chorus Master Claudio Marino Moretti, were in good voice. They were also choreographed in an imaginative and highly stylised manner by Marco Berriel, as in the scene of the Flemish prisoners, in which the chorus is used to intimidate Carlo by forcing him into a smaller and smaller space.

Carsen is certainly an imaginative director, and clearly knows how to stage opera. His presentation of “Don Carlo” was dramatically first rate, it was provocative, it was entertaining, it masterfully explored certain themes, and successfully developed flesh and blood characters, but it went way beyond what Verdi and his librettist had written, and more importantly it was an interpretation that was not supported by the music. It was great theatre, but it was not a “Don Carlo” many people would recognize. One might have thought it should have been retitled, Robert Carsen’s “Don Carlo” with music by G. Verdi.

Ultimately, it left one both impressed and irritated in equal measure.

Categories

News