Teatro la Fenice 2017-18 Review – Zenobia: Embracing the Past & Future To Create Compelling Performance in the Present

By Alan NeilsonMore than 300 years ago, in 1694, the small Venetian theatre of Teatro Grimani di SS Giovanni e Paolo presented Albinoni’s first opera, “Zenobia, Regina de’ Palmireni,” as part of the carnival season. It has now returned to Venice, this time at the Teatro Malibran, for only its second production in the modern era (The first being in Damascus in 2008). Attending a performance of a baroque opera is always a unique experience, it being near impossible to know exactly what to expect. The scores tend to be skeletal at best, requiring the musical director to make many decisions on how to present a complete musical reading of the piece, and given that many aspects of the baroque performance tradition can appear alien, and its underlying values distant to modern audiences, it forces directors to take numerous decisions on how to present the work in a way that can connect with the public. This production, overseen by Teatro La Fenice in performances aimed primarily at children, not only offered us the chance of seeing and hearing a real opera rarity, but also the opportunity of seeing how the directors engage with the work, and in what form they were able to bring it to the stage.

“Zenobia, Regina de’ Palmireni” may be considered to be a typical example of 17th century Venetian opera. Its plot, based loosely on real historical events, focuses on the glorification of a successful political and military leader who displays beneficent and wise judgment and exalts the values of restraint and mercy. Zenobia, who has rebelled against Rome, provokes Aureliano, the Emperor to attack Palmyra in order to return it to the Empire. In the process, he falls in love with Zenobia, who rejects him. Ormonte, a traitor responsible for Zenobia’s defeat, hopes to marry his daughter, Filidea, to the Emperor, but when this offer is rejected by Aureliano he tries to inveigle himself back into Zenobia’s trust by offering to kill Aureliano. Without knowing that she is being overheard by the Emperor, she rejects the plan and is rewarded by being returned to the throne. Ormonte, on the other hand, is spared death, but forced into exile. The opera ends with universal rejoicing. Honorable behavior is rewarded, treachery is punished and mercy is shown.

Embracing the Past

For this production for the Fondazione Teatro La Fenice in collaboration with the Conservatorio ‘Benedetto Marcello’ di Venezia, the conductor, Francesco Erle and the director, Francesco Bellotto combined to create a visually dazzling and musically inventive reading of Albinoni’s opera. For just less than two hours, the opera in three acts, performed without a break, delighted and captivated, in a production that was restrained and highly-stylized, which was unafraid of embracing and engaging with the traditions of the baroque theatre. There was no attempt to make the opera “relevant” or to compromise its underlying values. This was a bold, imaginative and successful attempt to present the opera in a manner which remained faithful to its traditions.

Erle produced a scholarly, yet innovative reworking of the score. Using Albinoni’s extant score, which included parts for strings, brass, and continuo, Erle added an array of colorful period instruments to evoke the Ottoman Turks of the Middle East and the middle Mediterranean of Greece. Thus we were presented with a sound world from three distinct geographical areas, areas in which 17th century Venice was engaged in a military and political struggle, the effect of which was to heighten the musical contrasts and add substantially to the dramatic quality of the work. The use of period Greek bagpipes to accompany an aria was an interesting example and proved to be notably successful. Moreover, Erle applied his considerable musical knowledge of the period to the recitatives, which were delivered with a considerable amount of variation, and proved to be engaging and lively, a long way from the sometimes dull forms associated with the genre.

Under Erle, The Orchestra Barocca del Conservatorio Benedetto Marcello di Venezia produced a compelling rendition of the work. Their playing was crisp, clear and exciting, and produced a well-paced performance – the only negative aspect being some occasional waywardness from the brass. There were numerous solo opportunities for the musicians, and all acquitted themselves with great credit, especially the flautist and bagpipe player, who standing high upon the city walls, produced wonderful accompaniments for the singers.

For his part, Bellotto decided to move the drama from its historical context to the year of its composition, choosing to view the opera as a valedictory work to mark the death of Doge Morosini, who had been in charge of the Venetian fleet during a number of successful campaigns against the Turks in the Eastern Mediterranean, and who had only recently died. Not only was Bellotto’s decision dramatically sound, but it was also a valid one, as the glorification of leaders or events on stage, through associations to a historical or mythological past was not uncommon. In any case, costumes were never necessarily time specific.

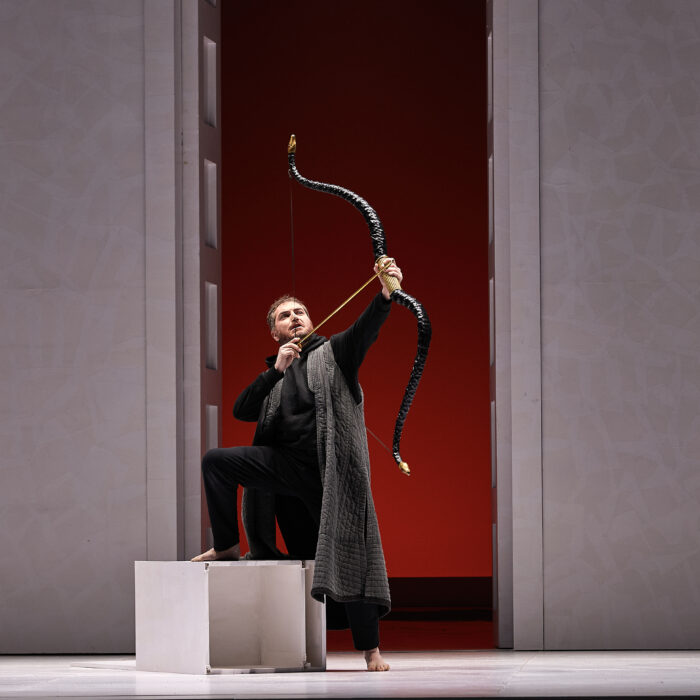

Bellotto was aided by a strong team, which included Carlos Tieppo (costume design), Massimo Checchetto (scenographer) and Vilmo Furian (lighting), all of whom worked in tandem to produce a visually sumptuous and vibrant staging. The set was simple, yet effective, comprising of the city walls of Palmyra, upon which the characters were able to walk. The dark walls also acted as a screen upon which it was able to project light or images. Tieppo’s costume designs were flamboyant and colorful and added to the flavoring of the production. Furian’s choice of lighting delightfully magnified the contrasts. In what appeared to be a further attempt to recreate the theatrical traditions of baroque theatre, which put a premium on spectacle, Erle had Aureliano end the opera by arriving deus ex machina, except rather than descending from the heavens he rose from the pit, in front of the conductor, faced the audience, lifted the Doge’s corno into the air and placed it upon his head. The Doge of Venice is equal to the Emperor of Ancient Rome.

A further inspired decision taken by Bellotto was to bring Erle and the orchestra into the drama itself: attired in a 17th century costume, Erle conducted the orchestra from the pit, alongside the continuo, with the rest of the players dressed in traditional black costumes as worn by Venetian patricians, sitting and standing on a raised platform towards the back of the stage, below the walls of Palmyra. This effect was to create a pleasing mise-en-scene, which integrated the musicians into the performance space in a meaningful manner.

The Future Before Our Eyes

All the roles were undertaken by students from the Conservatorio. Not only did they perform with enthusiasm, but also with a maturity and quality that belied their relative inexperience. Zenobia, dressed in a luxuriantly colored costume befitting her regal position, was essayed by the soprano Jimin Oh. She possesses a strong voice with a pleasing tone and displayed a secure technique and a solid coloratura. She displayed skill in embellishing the vocal line, and her phrasing was undertaken with confidence.

The countertenor, Danilo Pastore, playing the role Aureliano, in the guise of Venice’s Doge, looked every bit as if he had walked out of Raffael painting. Emerging from in-front of the conductor, dressed in red and gold, with long curly hair, with a helmet furnished with large red feathers he fitted perfectly the image of a character taken from the 17th-century stage. Acting the part in a detached manner, consistent with Ballotto’s vision of the piece, he characterized the role splendidly, his singing was cold, precise and measured. It was a very satisfying and promising performance indeed.

Also looking like youth from a Rafael painting, Federico Fiorio, another countertenor, who arguably made the most impressive contribution of the evening, in the role of Lidio. His voice has a pleasing tone and he displayed a high degree of vocal control with the ability to embellish the vocal line with a great deal of versatility and skill.

For reasons not at all obvious, Ballotto had the tenor Alfonso Zambuto play the part of Ormonte as a semi-comic, semi-ludicrous figure; at one point he was walking around the stage mimicking a robotic figure from a second-rate pop video. Possibly this was a concession made to entertain the children, but in the final performance of the run, for what was a normal adult audience, it came across as condescending and crass. Moreover, it irritated and detracted from what was otherwise a consistent presentation, in which passions were understated and controlled. Zambuto, however, acquitted himself well. He possesses a strong tenor with a pleasing timbre and displayed skill in characterizing Ormonte, despite the enforced comedic element.

Unfortunately, the soprano Naoka Ohbayashi, playing the part of Ormonte’s daughter, Filidea, did not do herself justice in the role. Her acting was fussy, her singing timid, and gave the impression that she was not particularly comfortable.

The mezzo-soprano Giuseppina Perna, dressed in red and gold, again with large red plumes adorning the helmet, put in a persuasive performance as Aureliano’s advisor. Her singing was refined and possessed an attractive coloring. Likewise, Dima Bakri, in the role of Zenobia’s advisor, gave a solid, although occasionally uneven performance. Her voice has a pleasing timbre, but her phrasing sometimes lacked subtlety.

The bass, Luca Scapin, dressed in a florid plebeian costume with a mask, a là commedia dell’arte, injected a successful comedic element into the role of the servant of Zenobia, Liso. As a low born member of the populous such buffoonery is to be expected and blended well into the overall presentation. Scapin made a very good impression, his voice strong with a pleasing color, which he used convincingly to characterize the role.

This was visually, dramatically and musically a wonderful production. It illustrated so well how with imagination and a little courage, baroque opera can be presented in a manner that it is capable of connecting to, and entertaining, a modern audience without the need to compromise its underlying performance values. There is no need for directors to engage in fatuous updating or for conductors to protect the audience from the tedium of too many recitatives. It is a real shame that it was only scheduled for performances over a threeday period.

For anyone with an interest in opera from the baroque period or who has interest in discovering its delights, in April a splendid production of Vivaldi’s “Orlando Furioso,” first performed at 2017 Festival Valle d’Itria, will be presented at the Teatro Malibran. It is a “must-see” production, and like “Zenobia, Regina de’ Palmireni,” it engages successfully with the genre on its own terms.