Teatro Comunale di Bologna 2022 Review: Lohengrin

Fisch Conjures Up A First-Class Musical Experience

By Alan Neilson(Photo: Andrea Ranzi)

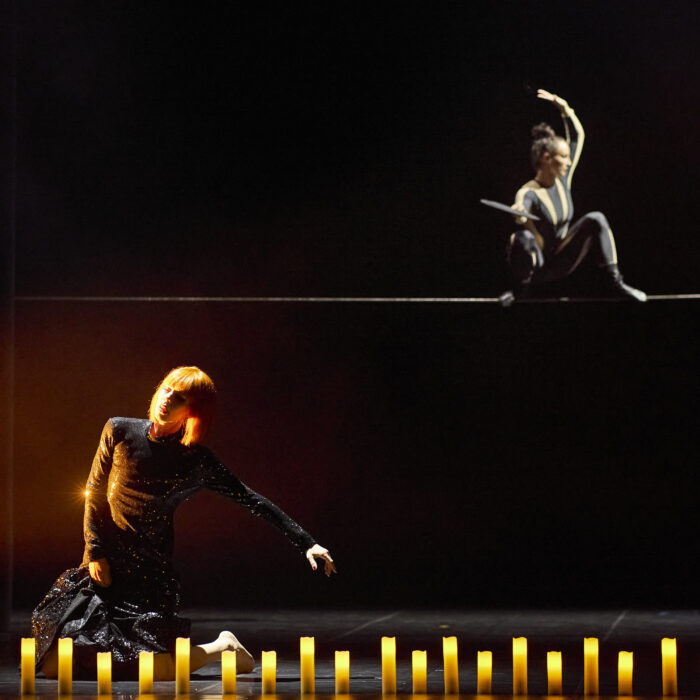

For the Teatro Comunale di Bologna’s final production at the Sala Bibiena, before its four-year closure for major refurbishment, it presented Wagner’s “Lohengrin” conducted by Asher Fisch and directed by Luigi De Angelis.

For those who like their operas to be a challenge, this production may have proved to be a worthwhile experience, but even then, this would have required a detailed reading of the extensive program notes and the lengthy interview with the director, which together took up over 11 pages in the libretto.

For those who believe that a stage work should be accessible without any necessary additional material provided by the director, they would have undoubtedly found the staging irritating, fairly dull and at times bewildering.

A Confusion Of Ideas

Although the overall thrust of the narrative was maintained, De Angelis’ inclusion of impenetrable pointers relating directly to his reading did little to illuminate the many, often obtuse, ideas that he tried to weave into his presentation. In fact, there were so many that even when reading the commentary, it was difficult to maintain a focus on the main themes as his explanations careered off into tangential meanderings and half-baked justifications. It was overwhelming. Possibly, if the audience had an hour or two to digest and reflect on his musings before the performance, then it would have all come together successfully. But surely, that is not what theatre is meant to be. Theater is a visual and aural experience in which the audience can lose themselves and be pulled into the world as presented on stage, not one to be deciphered by a text read before the show begins.

The main theme, according to De Angelis’ text, was the interplay that exists in “Lohengrin” between historical reality and the myth as experienced in a dream world. Elsa, through her dreamlike innocence, and Lohengrin, through his mythic status, provided bridges between these two worlds. Ortrud, on the other hand, is a connection to an earlier primeval age. Certainly, this is a reasonable interpretation, and the staging was partially successful in bringing this to the audience’s attention through the positioning of symbols such as a sword and a swan, while Elsa’s luminescent dress created an otherworldly impression. If he had focused on this one theme, he may well have met with success. Unfortunately, he did not. Instead, the ideas kept on flowing.

Judgement is clearly a central feature of the opera, but for De Angelis, this has a direct connection with today’s legal system, as we live in a society in which everyone and everything is judged. Everything takes place so quickly that judgments are made before trials even begin, and so we no longer recognize the rituals of being part of a community. Based on this analysis, the decision was taken to update the staging to the modern era. Although again, there was little in the staging to alert the audience to this, apart from the courtroom scene, which he explained was inspired by the Nuremberg trials.

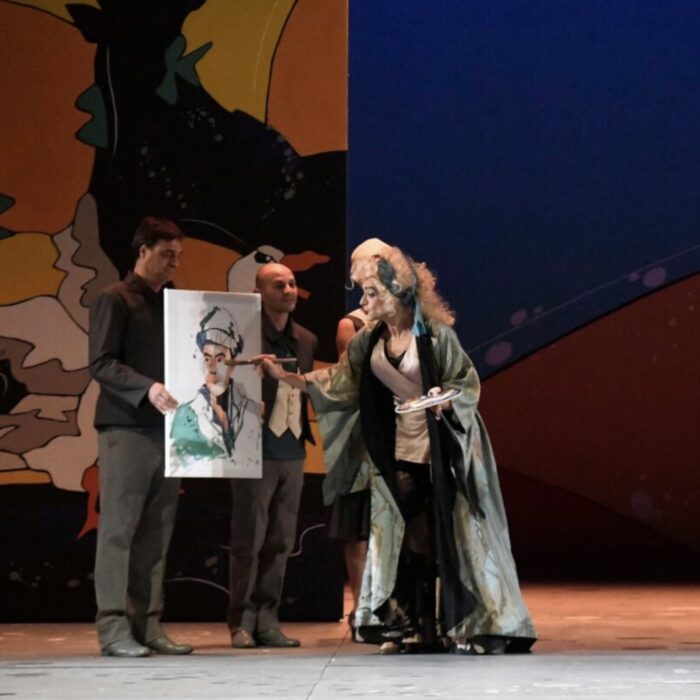

Throughout the performance, De Angelis had Wagner himself make a number of appearances. During the prelude, for example, we watched as the idea for “Lohengrin” came into his mind, which was played out against a misty, wooded backdrop. At one point, he was even seated in an auditorium box, watching the stage. These were, however, not simply random visitations by the composer; rather, De Angelis wanted to highlight that Wagner, as an artist, was demanding that the listener trust him, in the same way Lohengrin also demands absolute trust. As he goes on to explain, it is divine to prohibit doubt. Thus, as Lohengrin is a divine herald, so Wagner is a divine artist.

Nor did it end there. There were plenty more ideas. Yet the staging did little to reveal any of them with sufficient clarity. De Angelis deigned only to supply impenetrable hints of what he was trying to communicate. Ultimately, he was a victim of his own fertile imagination, enthusiasm and maybe a little self-indulgence.

De Angelis’ own company, “Fanny & Alexander,” was responsible for the set designs, costumes, lighting and videos, and to be fair, the staging did allow the opera’s simple narrative to assert itself, so that it was easy to follow even if it was constantly disturbed by opaque references to the multiple ideas he was trying to explore. Unfortunately, however, it also proved to be a visually dull experience, albeit one containing moments of inspiration. For example, the arrival of Lohengrin in his boat drawn by a swan, which is not an easy scene to bring alive, was very successful: a video on the back of the stage projected a tree-lined river scene that suddenly had occasional frames of a flying swan flicker in and out of the picture, brilliantly capturing the audience’s attention and alerting the audience to Lohengrin’s immanent arrival. Yet, even this was not what it seemed to be: the video was, according to De Angelis’ text, in fact, a collective hallucination.

Musical Excellence

The disappointing staging was more than made up for by a stunning musical performance under the musical direction of Asher Fisch, whose masterful control of the orchestra, chorus and soloists was first-rate. He produced a dramatically intense reading from the Orchestra del Teatro Comunale di Bologna, one in which he was happy to unleash its full power in order to create strong dynamic contrasts and magnify nuances while keeping up a strong forward momentum through the employment of brisk tempi. To the extent that the staging distanced the audience from the drama, Fisch’s orchestral sound was able to draw it back into its center.

Moreover, the balance he achieved between the stage and the orchestra was near perfect. Which, given the large chorus, in which the Coro del Teatro del Comunale di Bologna, under the guidance of Gea Garatti Ansini, was augmented by the chorus of the Accademico Nazionale dell’Opera e balletto ucraino “Taras Shevchenko,” under the management of Bogdan Plish, was impressive indeed. Such was the control, that the singers never struggled to be heard, and when all the forces combined, the sound was clear, strong and harmonious.

The production boasted a strong cast, although Vincent Wolfsteiner in the role of Lohengrin produced a rather workmanlike performance. His Lohengrin was two-dimensional with little in the way of depth or nuance; certainly he did not come across as a hero. His singing was strong but lacked color and, at times, the necessary passion. His performance was certainly not poor, but by comparison to the other soloists, he was not up to the same standard. His costume, which made him look more like a hobo than a knight, did him no favors at all.

Soprano Martina Welschenbach produced a pleasing, nuanced psychological portrait of Elsa with a fresh, lyrical presentation that captured her youth, innocence and fragility, although not at the expense of her underlying passions and insecurities. She possesses an attractive, versatile voice, which she used intelligently to craft detailed lines replete with colorful and emotional accents, allowing her to successfully flesh out her character. It is also a voice with a strong resonance, able to rise securely above the orchestra and chorus.

Soprano Ricarda Merberth threw herself wholeheartedly into the role of Ortrud. She possesses a versatile, secure voice, which she managed expertly to develop her character, whom she presented as suitably vicious, duplicitous and uncompromising. Her singing was direct and expressive, and her detailed and subtle phrasing impressed. In what was one of many excellently rendered scenes, she combined beautifully with Weschenbach for the second scene of Act Two in which Ortrud attempts to manipulate and poison Elsa’s mind. The two well-matched voices complemented each other exquisitely in the duet “Du Armste kennst wohl nie ermessen,” as Weschenbach’s long lines floated gracefully above Merbeth’s shorter lines who mused on her vengeance.

Telramund was played by the Italian baritone Lucio Gallo who regularly performs the German repertoire. His presentation was superbly fashioned to capture the demented ambition of his character with an energetic and expressive singing performance in which he convincingly coated his voice with his base emotions. His voice possesses a warm, appealing timbre which furnishes his singing with an attractive quality, which, for all his evil machinations, was never compromised.

Bass-baritone Albert Dohmen cut a fine figure as the king, Henry the Fowler, whom he portrayed as a confident, authoritative monarch. He is a singer with many years of experience and knows exactly what he is doing. His phrasing was beautifully and securely molded, with the right inflections and coloring to deepen the characterization and heighten his dramatic presence.

Baritone Lukas Zeman made a very good impression in the relatively small role of Araldo. His voice has a pleasing timbre, and his singing was expressive, clear and precise.

The cast was completed by the four knights, parted by tenors Manuel Pierattelli and Pietro Picone, baritone Simon Schnorr and bass Victor Shevchenko, and the four pages played by sopranos Francesca Micarelli and Maria Cristina Bellantuono and mezzo-sopranos Eleonora Filipponi and Alena Sautier. All produced fine performances.

The Teatro Comunale’s final production before the closure of the Sala Bibiena was undoubtedly a success. Musically, it was so good that it even managed to compensate, at least to a degree, for De Angelis’ less than convincing staging. For the next four years, while renovations take place, the opera will move to the Teatro Europauditorium.