Teatro Comunale di Bologna 2017-18 Review – Don Carlo: Maria José Siri & Luca Salsi Dominate Verdi’s Masterpiece

By Alan NeilsonVerdi made two distinct versions of “Don Carlos” plus a number of smaller-scale revisions. The original 1866 version written in French, was altered before its premiere, mainly for logistical reasons, as it was considered to be too long. The Italian version, written in 1884, with its Italian title “Don Carlo” contained extensive changes, most notably its reduction from five to four acts, the first act being completely deleted. As well as these two distinct versions, there also exist 3 revisions to the work, completed in 1867, 1872 and 1886. It is, therefore, correct to say that there exists no single definitive version, and producers are free to select whichever version suits their purpose or to combine elements from more than one version or revision. The Teatro Comunale di Bologna opted to present the 1884 version, without the ballet scene, which has the logistical advantage of shortening its running time, and the artistic advantage of sharpening its dramatic focus and is also generally considered to be musically superior. However, there are certain drawbacks with this version. The removal of the Fontainebleau scene removes the backstory from the drama, so that Carlo and Elisabetta’s love is not presented with its strong moral foundation, and thus does not capture the audience’s sympathy. The roles of Carlo and Elisabetta are both reduced, and in the case of Elisabetta has the potential to severely diminish her impact.

The production

In this production, the stage direction was undertaken by Henning Brockhaus, who chose to present a fairly traditional, albeit reasonably successful reading, in which the oppressive hands of the State, in the person of Philip II, and the Church, in the person of the Grand Inquisitor weighed heavily on the society. It is a society in which the dark fears of being identified as a heretic or a traitor are tangible. Everyone, apart from The Grand Inquisitor, were victims: Elisabetta, Carlo, Posa, Eboli, the courtiers, and the populace, even Philip himself, trapped in his role as King, were unable to escape the overbearing menace. Throughout the evening the figure of the Grand Inquisitor was a constant presence; seated upon his throne he watched in silence as the drama unfolded, intervening only when it was necessary to assert his control. The scenery, designed by Nicola Rubertelli, created a dark, claustrophobic and oppressive atmosphere; large dark flat walls towered above the stage, dwarfing the singers. It was also very mobile, and so could be easily maneuvered to intensify the claustrophobic effects or to open up the space when necessary. The costumes, designed by Giancarlo Colis, were Edwardian in style, but generally unimaginative and fairly dull. Therefore, their impact was fairly neutral. The scenic climax of the opera is undoubtedly the auto-de-fé, which Brockhaus presented in all its brutality, as the chained and bloodied, semi-naked heretics were led onto the stage, and paraded in front of the well-dressed dignitaries. They were then burnt, the flames consuming their bodies as the curtain fell. Not that this was a one-dimensional production, focused entirely on the oppressive nature of the Church and the State, for “Don Carlo” is a multi-themed work and other aspects such as the private versus public spheres, and love interests were accommodated with varying degrees of success.

Brockhaus also successfully integrated the lighter scenes into the drama. The second scene of the first act was particularly well-done, in which Princess Eboli, accompanied by a female chorus, sang her well-known “Veil Song.” Not only was it sung with an attractive, bright levity, with the chorus’ gracefully choreographed movements creating a happy, carefree atmosphere, but in this instance, Colis’ costumes were aesthetically pleasing, awash with pastel colors, and contrasting delightfully with the dark background.

There were, however, certain irritants that sat very awkwardly within the production, each small in themselves, but which cumulatively had an exaggerated negative impact on the drama. The example of Philip singing part of his aria, “Ella giammai m’amò,” with a yellow towel covering his head, was particularly disruptive as it immediately captured the attention; it not only looked ridiculous but diverted attention away from Philip’s inner turmoils. A further example was the decision to place colorful cushions and throws at the front of the stage in a symmetrical pattern, which appeared to serve no purpose other than to add color to the stark, bleak sets, yet simply undermined the oppressive atmosphere that had been otherwise so carefully crafted. However, by far the most damaging problem was that there seemed to have been too little attention paid to the acting. Each singer appeared to be free to follow their own instincts, sometimes very successfully, sometimes not so. The overall effect, however, created an uncoordinated feel to the drama.

An Unconvincing Lead

In the title role of Don Carlo was Roberto Aronica, who although having a strong and pleasant sounding voice, with a formidable upper register, failed to thoroughly convince in the role. There were two notable problems that fundamentally compromised his performance. Firstly, he was simply too loud, and not fully responsive to other singers. Of course, loudness in itself is not a problem, but when fortissimo is the default position and is combined with a lack of variation, thereby creating an imbalance in the ensemble, it certainly is. Secondly, there was insufficient attention given to characterization; the sound of the voice was pleasing enough, but Aronica’s presentation was too flat, too one-paced and failed to bring out the tensions within Don Carlo’s character. Ironically, in Act four, he did display a greater degree of sensitivity and combined well in the final duet, “È dessa! … Un detto, un sol,” with Elisabetta, but unfortunately, at the same time he started to have problems in the upper register, which up to this point had been in good shape. Despite the negative criticisms, Aronica has a very good singing voice and is pleasing to listen to.

A Strong Supporting Cast

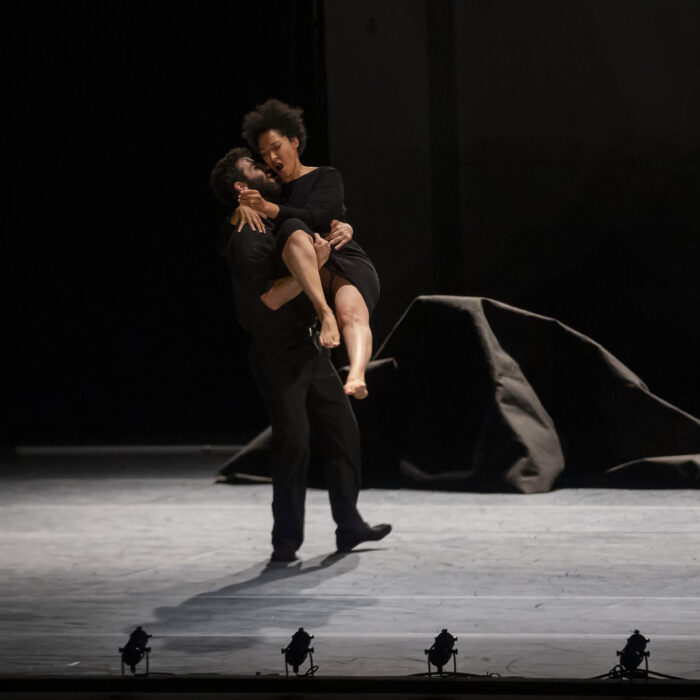

In the 1884 version of “Don Carlo” there is always the risk that Elisabetta will be overshadowed by a dominant Princess Eboli. It is, therefore, essential that she can redress the balance in Act four, which provides her with two excellent opportunities to assert herself. Certainly, early in the opera, it did appear that Maria José Siri, playing the role of Elisabetta, was indeed losing ground to Eboli. Her portrayal as an aloof, distant and self-contained Queen meant that she rarely attracted the necessary attention, irrespective of her vocal performance, which had always been of a high standard. Her Act four aria, “Tu che le vanità,” however, in which she laments Carlo’s plight, the love that never was, and now yearns only for death was presented with such profound feeling that any such impressions were quickly despatched. Siri, displaying her technique to the full, produced a riveting rendition in which her rich vocal pallet, subtle dynamic infections, and wonderful control brought meaning and emotional depth to every phrase. Immediately following on from this, Siri engages in a duet with Carlo, in which they say their final goodbyes and hope to meet again in a better place. Again Siri displayed a talent of rare quality, as she caressed each line with tenderness and beauty, and blended sympathetically with Aronica’s Carlo.

Luca Salsi, who played the role of Posa, has a notably powerful voice, and created a strong portrayal of the Marquis, despite his dull and insipid costumes, which amounted to no more than commonplace plain suites. He possesses a wonderfully warm and expressive baritone, which he used with a great deal of flexibility. His Act three aria, “Per me giunto è il di supremo” in which he takes his farewell of Carlo was sung with great sensitivity, his voice spinning out long heart-rendering lines. Unfortunately, the Act one duet with Carlo, “Dio, che nell’alma infondere,” was not the high point it should have been as the voices did not easily combine, and was too disjointed in its presentation. On the other hand, Salsi’s recitatives were superbly delivered, their meaning always carefully articulated, sustained by his excellent technique and intelligent phrasing

Veronica Simeoni in the role of Princess Eboli produced a truly fabulous performance. Dressed as a platinum blond vamp, reminiscent of a 1920s silent film star, she acted out the part with real zest. In the well-known “Veil song” from Act one in which she displayed her wonderful crystal clear coloratura, trills, and delightful embellishments was, in fact, outdone by her Act three aria “O don fatale, o don crudel,” in which she rails against the curse of her own beauty, and accepts life in a convent. Simeoni clearly portrayed Eboli’s anguish: each line beautifully phrased, her words intoned with wonderful clarity and gracefully ornamented, her upper register shining brightly, and once again exhibiting her fine coloratura. It was a gripping and forceful vocal performance, underpinned by excellent acting.

In Act three, alone in his room, King Philip, played by Dmitry Belosselskiy, in the aria “Ella giammai m’amò” reflects on his position as King of the Spanish Empire, on his failing marriage, loneliness, isolation, and his own mortality. It is the point in which Verdi focuses on the cavernous gap that exists between the public figure and the private man, in which Philip’s private emotional and psychological travails and suffering are on display. The aria requires great sensitivity and skill on the part of the singer, and Belosselskiy did not disappoint. Inflecting his warm, resonant bass with an array of subtle colors and dynamic shadings he wrapped every line in self-pity, overlaid with heavy resignation, with occasional flashes of defiance, and captured the very personal tragedy of the most public of figures. In a production with many standout performances, this was certainly one of them.

This aria is immediately followed by a duet with the Grand Inquisitor, “Sono io dinanzi al Re,” and is, in essence, a power struggle between the State and the Church. The scene requires two strong personalities, who engage in a vocal battle, in which the King is eventually worn down by the Grand Inquisitor’s greater authority, reminding the King that he too could also be brought before the Inquisition. The two basses, Belosselskiy and Luis-Ottavio Faria, playing the part of the Grand Inquisitor, sang well, but Faria’s voice is slightly smaller and carried less authority, which meant that it did not quite work dramatically, for although the timbre of Faria’s bass beautifully complemented Belosselskiy’s, he failed to dominate. Nevertheless, Faria played the part very convincingly in portraying the sinister and gnarled Inquisitor in all his intransigent malevolence.

Nina Solodovnikova, took the role of the Queen’s page, Tebaldo, in her stride, and produced an excellent performance. Her voice has an attractive timbre, full of youthful vitality.

Luca Tittoto in the small role of the monk, who appears at the opening and closing of the opera, made an excellent impression. His deep, forceful bass resonates with authority. His diction crystal clear.

The Coro del Teatro Comunale di Bologna under the direction of Andrea Faidutti was in sparkling form and delivered an engaging and compelling performance.

The Orchestra del Teatro Comunale di Bologna, under the direction of Michele Mariotti, perfectly captured the tinta of the opera, casting its dark musical shadows over the drama, whilst never allowing it to become monotonously gloomy. This was a wonderfully detailed reading, full of sharply defined textures and pleasing contrasts, underpinned by a finely calibrated sense of balance. The orchestral sections were always firmly under control; there were no awkward squalling sounds from the brass, which blended seamlessly into the musical landscape, whilst the strings produced a truly luscious sound. It was a splendidly nuanced performance, full of subtle dynamic and rhythmic interest. On the negative side, however, although Mariotti was always attentive to the singer’s needs, he occasionally allowed the balance to shift too much in favor of the stage.

This was a high-quality production from the Teatro Comunale del Bologna, with many outstanding vocal contributions, underpinned by first class playing from its orchestra under Maestro Mariotti. Even the staging which did not always convince did enough to promote the drama and keep the audience engaged. Strangely, this was a production that was more than the sum of its parts, its (minor) failings doing little to detract from its overall quality.