Teatro alla Scala 2024-25 Review: L’opera seria

Conductor Christophe Rousset & Outstanding Creative Cast Revive an 18th-Century Masterpiece

By Bernardo Gaitan(Photo credit: Brescia and Amisano)

One of the most common phenomena of the 18th century was the pilgrimage of European composers to Italy, seeking to immerse themselves in the “alla italiana” compositional technique and then return to their homelands to apply this revolutionary formula. Such was the case of Florian Leopold Gassmann (1729–1774), who left his native Bohemia to settle first in Bologna and then in Venice, where he enjoyed a taste of success. As a gesture of gratitude for Italian hospitality, he returned to Vienna bringing with him a very young–and still unknown–Italian musician of just 15 years: Antonio Salieri. Ironically, it would be this young man who would eventually take over the royal position left vacant by his mentor, beginning his own path to glory in the Austrian capital.

Gassmann’s time in Italy left an indelible mark on him. Italians, with their innate theatricality, are dramatic not only onstage but also in everyday life. It’s likely the composer found himself caught in such extravagant situations within the theaters that they deserved to be told, even to those with no connection to the operatic world. Thus was born, with a libretto by Ranieri de’ Calzabigi, “L’opera seria:” a work conceived as a stern critique of the pre-reformist opera Gluck was reacting against, which ultimately evolved into a masterfully crafted parody of the backstage vicissitudes of the operatic universe. And despite its misleading title, it is not a seria opera, nor even a buffa one…it’s a buffissima!

Production Details

What is most fascinating about this work is its astonishing relevance: the conflicts it portrays around opera production are still extraordinarily timely. The plot itself is quite trivial, yet it preceded titles like “Ariadne auf Naxos,” “Le convenienze ed inconvenienze teatrali,” or “Der Schauspieldirektor”—all staples of metatheatre. Even the characters’ names hint at theatrical mockery through clever wordplay. The story revolves around the misadventures of Fallito, a theater impresario, whose name could translate as “Failure,” who is in the creative throes of a new opera, dealing with the delirious demands of the composer Delirio (Delirium) and the librettist Sospiro (Sigh). Who should he please? The artists or the performers?

The singers Ritornello, Porporina, and Stonatrilla, whose name might be loosely rendered as “Screechy,” impose their whims: demanding changes to the libretto, scenic alterations, and added lines for personal spotlight. Basically all the requests that still echo in today’s opera productions. Meanwhile, the creative team fiercely defends the integrity of their work. The result is a total disaster. To avoid the audience’s wrath, Fallito flees with the box office earnings, while the whole company joins in a final oath: “Noi giuriamo qualunque impresario di far sempre fallire o crepare” (“We swear always to ensure that any impresario will fail or drop dead”).

This production, originally staged at the MusikTheater an der Wien, was presented by La Scala under the stage direction of Laurent Pelly. The Parisian director’s work was spectacular and unprecedented: a comedy choreographed to the millimeter, with impeccable comic timing, where physical gags and precise interaction with stage machinery were key to the coproduction’s overwhelming success. The costumes, also designed by Pelly, were period for all characters except Fallito, who wore a modern suit and tie. A clearly symbolic choice: the problems of opera production are as old as they are current, recurring since the Viennese premiere in 1769 and, in all likelihood, continuing far into the future.

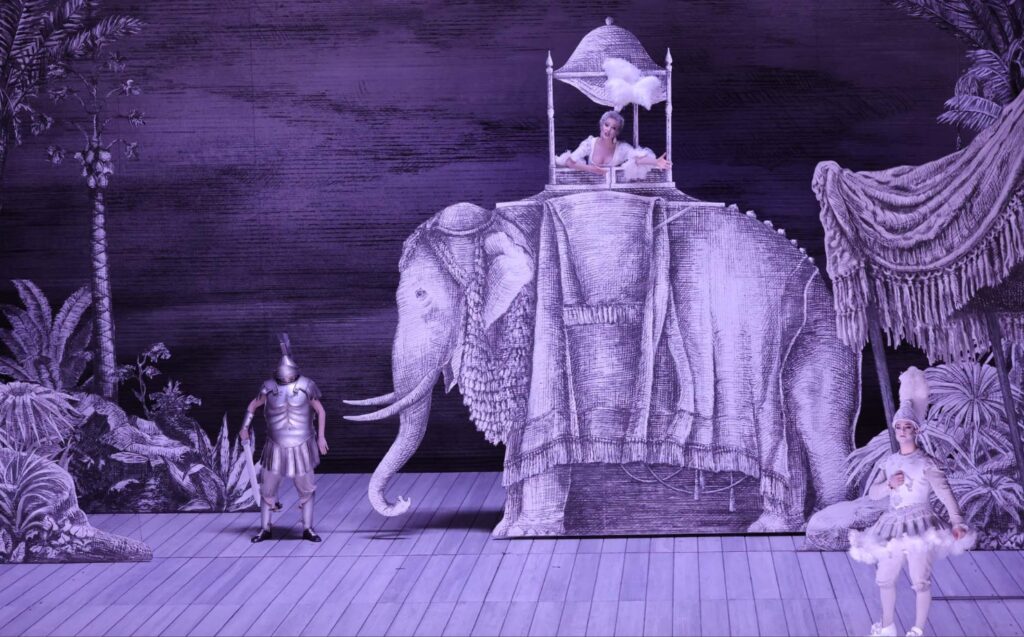

The set design by Massimo Troncanetti evolved with each act. In the first, a black backdrop with three white doors; in the second, a richer scene evoking a famous alla italiana rehearsal with all props brought in by mime-stagehands; and in the third, during the performance, a caricatured take on classical theater with surreal elements, such as the appearance of an elephant. This act was a comic frenzy: singers tangled in the set, a soprano entering with the score in hand, a tenor improvising the text, dancers—choreographed by Lionel Hoche—completely out of sync, and as a grand finale, the set collapsing and glass shattering during the prima donna’s aria. A hilarious chaos that drew genuine belly laughs.

Musical Highlights

The excellent musical direction was led by Christophe Rousset, at the helm of Les Talens Lyriques along with period instrumentalists from La Scala. His interpretation was a lesson in philological precision, clarity, and vibrant theatricality. An undisputed master of the Baroque repertoire, Rousset infused the score with rhythm and lightness, supporting the singers with sensitivity and highlighting stage comedy with musical intelligence.

Pietro Spagnoli led the cast as the ill-fated impresario. Spagnoli is a living monument to Italian comedy: his performance perfectly balanced vocal elegance and meticulously carved diction. It’s no surprise he defines himself as a musicante teatrale (theatre musician): his powerful phrasing and flawless enunciation turn each line into a sculpted sound.

The tragicomic duo of Mattia Olivieri (Delirio, the poet) and Giovanni Sala (Sospiro, the composer) embodied the clash between creation and frustration. Olivieri shone as a neurotic, perfectionist artist, delightful in his sparkling acting and with a firm, agile, expressive voice. Sala, on the other hand, found in Sospiro the perfect opportunity to showcase a refined style, with precise high notes and a finely polished vocal line.

Tenor Josh Lovell, in the role of Ritornello, was a true revelation. His clear timbre and Mozartian charm was combined with solid technique and an engaging stage presence. He starred in one of the show’s funniest scenes: attempting to rewrite the libretto to his liking. The character of Passagallo, the dance composer, took on unforgettable dimensions thanks to Alessio Arduini. With a warm and confident voice, Arduini proved to be a complete actor: moving gracefully and turning each appearance into a gem of musical and gestural comedy.

The female trio was another cornerstone of this production. Julie Fuchs, as Stonatrilla the prima donna, embraced her role with flair and brilliance. Her arias, brimming with extreme virtuosity, were delivered with dazzling ease. The French soprano flaunted her high notes shamelessly, with grace and cheek, starring in a solo scene that guaranteed roaring laughter. Andrea Carroll, as Smorfiosa, the second lady in rank but not in vocal or stage quality, played a tragicomic character plagued by insecurity. With self-irony and warmth, the American soprano brought to life a consistent and endearing figure, gracefully navigating small challenges at the extremes of her vocal range. Serena Gamberoni, as Porporina, the secondo uomo and traditionally a cross-dressed role, stood out with character and resolve. Her vocal control, clear diction, and elegant tone defined a luminous and precise character.

A particularly delightful moment came from the singers’ mothers -Bragherona, Befana and Caverna- who made a star appearance to defend their daughters with insults. Tenor Alberto Allegrezza, and countertenors Lawrence Zazzo and Filippo Mineccia, clad in grotesque foam costumes, delivered a riotous scene. Their intentionally ridiculous voices created a comic whirlwind that swept away any notion of family harmony.

The revival of this forgotten gem is part of La Scala’s commendable project to rescue ancient titles. “L’opera seria” now joins a lineup that includes “La Calisto,” “Li zite ‘ngalera,” and “L’Orontea.” Despite its three and a half hours of running time, the brilliance of the staging makes time fly, offering a delightful rediscovery of this 18th-century masterpiece.