Staatsoper unter den Linden 2025-26 Review: ‘Das kalte Herz’ (The Cold Heart)

World Premiere of Matthias Pintscher & Daniel Arkadij Gerzenberg’s New Work Reveals a Poetic and Dark Journey of the Soul

By Zenaida des Aubris(Photo: Bernd Uhlig)

Matthias Pintscher’s new opera, “Das kalte Herz” (The Cold Heart), with a libretto by Daniel Arkadij Gerzenberg, is not a retelling of German author Wilhelm Hauff’s famous fairy tale from 1827—that text written in the spirit of the Biedermeier period, which can be read as a subtle critique of early industrialization and unbridled capitalism—but rather its condensation and transformation into a psychological musical theater of the present that explores the existential question: What happens to a person who wants to free themselves from their own feelings?

At the center is Peter, a man whose heart appears less as a biological organ than as a place of vulnerability, memory, and longing. Feelings become an imposition, a burden, a pain. The desire to silence his heart becomes the driving force of the plot.

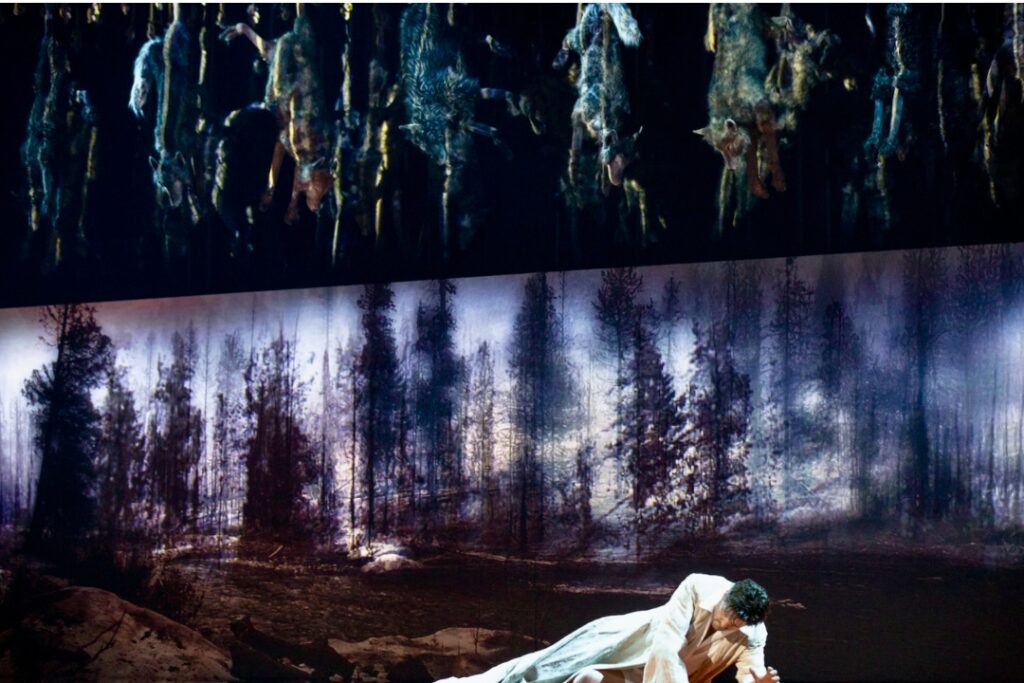

The opera unfolds in a realm between reality, dream, and myth. The forest—still a fairy-tale topography in Hauff—becomes an inner landscape, a psychological space in which voices, memories, projections, and dark forces appear. The figures appear less as realistic characters than as reflections of inner states.

(Photo: Bernd Uhlig)

The famous heart swap–the organ for a heart of stone—in the fairy tale is not played out naturalistically, but as a symbol, and a ritual act of self-alienation: performed by Peter’s own mother after she is incited to do so by the ancient Egyptian deity Anubis and the Old Testament figure Azazel. Peter attempts to amputate his own inner life—and in doing so experiences the radical impoverishment of his existence. The more he withdraws emotionally, the more ghostly, empty, and isolated his world becomes. Intimacy breaks down, language loses its hold, relationships dissolve into shadows.

Pintscher and Gerzenberg are less interested in plot than in states of being: in the liminal zones between desire and paralysis, between memory and loss, between sound and silence. The drama arises not from external events, but from internal shifts.

In the end, there is no simple redemption in the fairy-tale sense, but a fragile, open movement back to sensitivity—the inkling that humanity is only possible where vulnerability is allowed. “The Cold Heart” thus becomes an opera about the imposition of feeling—and about the danger of losing oneself through self-protection.

Director James Darrah Black has the characters perform in twelve impressive, if enigmatic, rooms designed by Adam Rigg, complemented by Molly Irelan’s imaginative costumes. After the first scene with projections of a forest, at least two dozen very naturalistic stuffed wolves suspended from meat hooks descend from the fly tower. Is this drastic symbolism an allusion to the dictum of the English philosopher Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) “in the state of nature, man is a wolf to man”? In any case, this interpretation would fit conclusively into the further philosophical references of the production.

(Photo: Bernd Uhlig)

Matthias Pintscher, who conducted the world premiere himself, said he composed “with a broad brush.” The result was a mixture of acoustic extremes: strings of horrific drama, wolf-gorge romanticism, plus finely crafted echoes of Wagnerian motivic technique, accentuated by richly scored percussion. The Staatskapelle Berlin performed this multi-layered score with great precision and presence.

The singers were the most convincing. Samuel Hasselhorn portrayed Peter with a smooth baritone as a searching, torn protagonist who, until the very end, is unsure whether he has wished for–or received–the right thing. Katarina Bradić impressed as the mother with a convincing mezzo that made the character’s ambivalence between care and guilt palpable. Rosie Aldridge dominated the ritual scenes as the goddess Anubis with her imperious, powerful mezzo. Sunnyi Melles took on the speaking role of Azaël: a desert demon, sin-eater, a hermaphroditic figure who deliberately comes across as anything but sympathetic. Against these mythological primal forces, Peter’s girlfriend Clara—sung by Sophia Burgos with a crystal-clear soprano—ultimately stands no chance as the embodiment of closeness and warmth.

After 90 minutes without intermission, many questions remain unanswered, and much demands interpretation. But does one really want to spend time searching for answers? The rather restrained applause from the premiere audience gave its own answer to that question.

Categories

Reviews