Seattle Symphony 2019 Review: Orfeo ed Euridice

The Boston Early Music Festival Brings Jaroussky’s ‘Orfeo’ Pastiche to Seattle

By John Carroll

Early music enthusiasts in Seattle showed up in full force for a single concert performance of a Baroque pastiche of the Orpheus story featuring world-class early music specialists. How could they resist the intriguing concept and such a stellar line up?

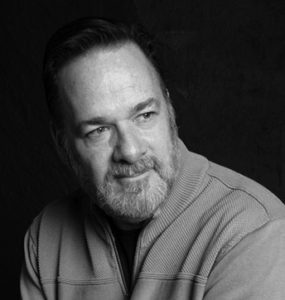

Philippe Jaroussky is a major international star (a “rockstar countertenor” as the Seattle Symphony marketing department awkwardly posits) with nearly 20 solo recordings over this past decade.

Amanda Forsythe is surely at or near the top of any list of Baroque sopranos. And the Boston Early Music Festival has an expert reputation built over 40 years. Add in the timeless tale of Orpheus and his beloved bride, and it was a “can’t miss” evening for an audience that was so grateful they offered a partial standing ovation at intermission.

Baroque Ordered A La Carte

Jaroussky’s program notes state that his affinity for 17th century Italian opera led him to conceive and construct this “Orfeo ed Euridice” as “a kind of opera in miniature or as a cantata for two solo voices.” This version of the Orpheus myth is focused only on the two title characters and curated from music by seven composers. Claudio Monteverdi, Luigi Rossi, and Antonio Sartorio provide the most music with several arias and duets each; the other composers are featured in instrumental interludes, except for a short vocal section by Agostino Steffani.

Although the works have a 65-year spread between them (Monteverdi in 1607, Rossi in 1647, Sartorio in 1672), they are similar enough in style that they dovetail nicely and provide a rich overview of vocal music across nearly a century. The overall concept is extremely effective, distilling the legendary story to its essence.

Concerns about hearing such a small chamber ensemble playing original instruments in a very large symphonic hall were well-founded at first as there was an opaque quality to their sound. An acoustic murkiness made it hard to discern the 10 individual instruments and swallowed the small details at the heart of early Baroque music.

However, as the evening progressed, the space magically seemed to respond to the intimacy of the music and allowed more nuances to shine through. The Boston Early Music Festival Ensemble played exquisitely under the co-direction of Paul O’Dette and Stephen Stubbs, who contributed themselves on the chitarrone and the Baroque guitar respectively. Concertmaster Robert Mealy led the team effortlessly (or so it seemed).

A Heavenly Soprano in Hades

After a short overture and two duets from Sartorio and Monteverdi that were unmemorable, soprano Amanda Forsythe seized the first chance to make an impact in Rossi’s aria for Euridice, “Mio ben, teco Il tormento.” In this calm and elegant aria, Forsythe unveiled a pure and poised lyric voice. Using all the ingredients of her technique — volume, placement, breath, vibrato, ornaments, intensity, color — she sculpted the long musical phrases into ravishing statements of steadfast devotion to her new husband.

Later, the sudden bite of the serpent was strikingly effective as her music jolted from a jaunty chorus by Rossi (sung as a solo by the soprano) into an aria by Sartorio (“Ahimè, Numi, son morta”). Forsythe suddenly shifted her demeanor and wilted as the venom drained the life from her body and color from her voice. In death, she reclined gracefully into a chair at center stage and slowly closed her score.

Euridice came back after the intermission as a vision, hovering above the audience in the box seats to the left of the stage. Sartorio’s “Ombra d’Euridice” was another showcase for Forsythe’s exquisite and passionate vocalism, with the middle section “Se desti pietà” suspending time as only a supernatural creature could.

All evening long her pitch and intonation were flawless. And even in a fairly static concert performance with scores in hand, Forsythe used her bright eyes and elegant presence to connect emotionally with both the audience and her partner.

The “Rockstar” Finishes Strong

Mr. Jaroussky didn’t make an impact until the second half of the program. This is partially due to the way the work unfolds, with the Euridice leading the story until her death when the focus shifts to Orfeo’s grief and his quest to bring her back to life. Unfortunately, it was also a result of patches of tonal insecurity and tension in Jaroussky’s vocal production.

His first aria, Monteverdi’s “Vi ricorda,” was choppy with high notes that sounded hen-pecked. The big emotional aria after he discovers Euridice’s dead body (Rossi’s “Lagrime, dove sete?”) was labored. In the top portion of his range, his neck and jaw tightened, constricting the tone and giving the sense he was bumping up against a ceiling instead of the open sky where he might soar even higher.

After the break, the pathos of the music brought out Jaroussky’s strengths and his voice opened up. Monteverdi’s “Possente spirto,” an early watershed moment in operatic expressiveness, was hauntingly sung. In this long aria, Orfeo tries through the magic of his music to persuade the boatsman Charon to escort him across the Styx river to rescue Euridice from Hades. In the aria’s first stanzas, two violins echo the singer and each other in rising and falling figures, interspersed with intricate and intense embellishments known as “cantar passaggiato” according to the instructive program notes by Jean-François Lattarico. In the next stanzas, the harp steps in to be Orfeo’s echo as his vocal filigree intensifies. Jaroussky pleaded Orfeo’s case with soaring tone, wedding the virtuosity to searing emotional conviction.

Orfeo’s plan almost works, but he loses Euridice forever at the last moment due to his mistrust. Orfeo is, of course, shattered and expresses his regret and sorrow in Rossi’s “Laciate Averno,” which closes the work. In Jaroussky’s masterful hands, this solemn aria gradually diminished to repeated near-whispers of “A morire!” as he fell to his knees and the lights slowly faded out in silence.

The unexpected encore, Nerone and Poppea’s final love duet “Pur ti miro, pur ti godo” from Monteverdi’s 1643 “L’incoronazione di Poppea” seemed to be offered as an alternative happy ending to the tragic story. It was beguiling with the two high voices married in a silky blend.

The concert was thoughtfully staged. In such an intimate world, small gestures or details can help tell the story. I have already mentioned how Euridice sang from up in the box seats during the time she was in Hades to haunting effect. Another nice touch was a change of attire for Jaroussky for the second half after Euridice’s death; instead of the standard black tie tuxedo of the first half, he wore a black collared dress shirt unbuttoned at the neck. The single white rose he carried was placed center stage and offered to her in the opera’s final moments.

What a remarkable privilege to take refuge from modern life for two hours in a world of music that is 400 years old and a story that goes back thousands of years, a testament to the timelessness of great art and the talents of all the artists involved.