Seattle Opera 2023-24 Review: Das Rheingold

Greer Grimsley, Frederick Ballentine Star in Visually Arresting Production

By Gavin Borchert(Photo credit: Seattle Opera © Philip Newton)

Why build an elaborate faux-underwater set for the Rhine scenes in Wagner’s “Ring” when you have an orchestra pit that can make a perfectly plausible stage river? It’s an idea so obvious, you think surely, it must have been tried already.

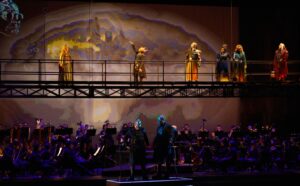

This is the solution found by Brian Staufenbiel, tasked with staging “Das Rheingold” for Minnesota Opera. It performs in St. Paul’s Ordway Center for the Performing Arts and doesn’t have a pit large enough to comfortably accommodate Wagner’s full orchestra. Staufenbiel put the orchestra onstage and placed the action in front of, above on a stage-spanning catwalk, and within it. He then enhanced it all with projections, sometimes abstract and sometimes representational, on the rear wall and front scrim.

Visually Arresting

It sounds like a concert performance, with or without the euphemism “semi-staged.” But, in this production, which Seattle Opera has borrowed to open its 60th season, it’s so much more. This “Rheingold” is visually arresting but flexible and light on its feet. There was no loss of epic grandeur, mythic atmosphere, emotional impact, or musical power. The run opened August 12 and continues for three more performances through August 20.

Seattle Opera continues its legacy as America’s premier Wagner company. They built a global reputation based on their “Ring” productions annually, from 1975 to 1983, and then sporadically. They then settled into a quadrennial schedule, with their most recent “Ring” performed in 2013. In addition, Seattle Opera has staged Wagner’s other six mature operas. The company states on its website that it has no plans for complete “Rings” in the near future. Since its modus operandi, Seattle Opera has inevitably worked towards the full four-opera cycle by staging the operas individually first. They presented excerpts from “Die Walküre” outdoors in the summer of 2021 to celebrate a return from the pandemic hiatus. Both that performance and this season’s “Rheingold” were led by former Seattle Symphony music director Ludovic Morlot and it looks like they will be gearing up for a full Morlot-led “Ring” before too long.

Seattle Opera could do worse than to bring back Staufenbiel to stage the other three operas using his approach. The company’s 2013 “Ring” was the fourth go-round after its 2001, 2005 and 2009 productions. Stephen Wadsworth’s very popular and naturalistic staging, inspired by the natural beauty of the arboreal Northwest, became known as the “Green Ring.” Its main forest glen set was made so that one might be able to smell the pine needles. But, this style of stage-filling is immobile and many scenes inevitably had to be staged around it, which cramped the stage front.

Staufenbiel’s staging doesn’t have that problem. From floor to catwalk, front to back and in the pit, it places the action all over the theatrical space. The pit serves not only as the Rhine, but as the subterranean realm of the Nibelungs. The catwalk is the rainbow bridge the gods traverse to Valhalla at the opera’s triumphant conclusion. Stripped down, the set also bows to current economic realities. But, given the choice between spending money on trees and fake rocks, and spending money on musicians, I’ll choose the latter every time.

Much is being made to promote Staufenbiel’s high-concept rationalization for his staging. One may have seen the placards in the lobby and an essay in the program book. “I sought to connect Wagner’s mythical realm with the mysterious complexities of our technological era … Gods are part human, part machine,” said Staufenbiel. Seattle Opera is even touting the term “techno-Ring” as a descriptor in hopes, presumably, of replicating the advertising hook of its previous “Green Ring.” This concept is manifested primarily in images of gears and maze-like computer circuits in its projections, and need not concern you. But, if you like, feel free to ponder the parallels between Wotan’s treachery in building Valhalla and stealing the ring for his own power and our society’s current hubris concerning unregulated technological advancement and climate change.

Fresh-Voice Cast

Most of the action is placed in front of the orchestra to enhance vocal audibility. It is a boon with this production’s fresh-voiced cast. From top to bottom, it has to be the most winningly and attractively sung “Rheingold” in Seattle Opera’s history. In fact, it is overall the best-sung Wagner production I can recall there. It was a thrill to hear that Greer Grimsley would be returning as Wotan. He is a veteran Seattle Opera favorite in Wagner and as several other villains, including Jack Rance in “The Girl of the Golden West” and Mephistopheles in “Faust.” He brings a dark, rich, and authoritative bass-baritone to the role.

Another returning favorite is the almost intimidatingly versatile Frederick Ballentine, who at Seattle Opera preceded his “Rheingold” Loge with “Carmen’s” Don José and Charlie Parker in “Charlie Parker’s Yardbird.” Staufenbiel’s vision of “Rheingold” is not only scenically innovative, with Ballentine’s vivid characterization to work with. This production places Loge, the opera’s moral conscience, at its dramatic center and clashes with Wotan as his equal. It is a balanced pair of pro/antagonists.

Others in the cast hinted powerfully at a bright Wagnerian future. Michael Mayes was a fantastic Alberich. Peixin Chen as Fasolt could also make splendid Wotans at some point. Katie Van Kooten as Freia is ready to triumph as Sieglinde. In her Seattle Opera debut, Denyce Graves sings Erda. There were a couple of rough moments when the contrast between her shimmering top and earthy lower ranges were hampered. More beautiful and captivating singing was provided by Melody Wilson as Fricka, Kenneth Kellogg as Fafner, Viktor Antipenko as Froh, Michael Chioldi as Donner, Martin Bakari as Mime, and Jacqueline Piccolino, Shelly Traverse, and Sarah Larsen as the Rhinemaidens.

One more detail to mention is the irony of the title prop as the ring itself and for the entire cycle. The MacGuffin, the driver of the plot, is normally invisible to the audience. Staufenbiel got around this simply by making it not a finger-sized ring, but by something grasped in the fist like brass knuckles and constructing it with light. Imagine that: a ring we can actually see.