Seattle Opera 2021-22 Review: The Marriage of Figaro

Soraya Mafi & Ryan McKinny Shine in Mozart’s Classic Masterwork

By John CarrollEvery element in Seattle Opera’s “The Marriage of Figaro,” which I saw on opening night, focused the production into a sunny comedy brimming with goodwill.

You’d have to look hard to find any political overlays, class resentment, sexual aggression, or personal bitterness on stage amidst the humorous antics. Any elements of the story that might harbor threats of dark antagonism were glossed over or performed with a knowing wink to assure the audience that a happy ending was guaranteed.

The production’s upbeat, quicksilver point of view was immediately established by conductor Alevtina Ioffe’s fleet reading of the overture. Her tempo pushed so close to the line of being too fast that I was concerned some articulation of the rapid figures would get lost — but the orchestra, made up of members of the Seattle Symphony, held it together masterfully.

Ioffe kept the pacing brisk throughout, asking for pinpoint deftness in the rapidly delivered recitatives and opting for crisp tempos in the more pensive arias, such as the Countess’s “Porgi amor” and “Dove sono.” She seemed to have no interest in slowing down to lean into Mozart’s most sublime moments like the gorgeous letter duet, Figaro’s “Tutto è tranquillo e placido” in the final act, or even the legendary “Contessa perdono” finale. They registered merely as thoughtful reflections within the forward momentum of the comic plot of mistaken identities, clever contrivances, and innocent assignations.

A Couple to Root For

Though an ensemble piece, the opera centers on the relationship of the valet Figaro and the lady’s maid Susanna — it’s their story, their wedding, their impetus to be happy and overcome obstacles to their happiness. I left Seattle’s production convinced that Figaro and Susanna are opera’s coolest couple due the remarkable chemistry between soprano Soraya Mafi and bass-baritone Ryan McKinny. Some of the bride and groom’s interactions in the work could be played with darker layers of angst and suspicion, but not here. This was an endearing team from start to finish. Together they had spark and sparkle, finishing each other’s thoughts, gestures, and phrases as close-knit couples do. From their clever opening duets to their sweet “Pace, pace mio dolce tesoro,” Mafi and McKinny were always in sync, a winning couple to truly root for. I would love to invite them over for brunch.

With his energetic yet easy-going physicality and the friendly twinkle in his eye, Ryan McKinny was an ideal Figaro for a production that emphasized charm and comedy. His smoothly produced voice had warmth and color – and how nice to hear the low notes of the role resonate so solidly, with no loss in the upper register. Every one of his arias, duets, and ensembles was played just right, not a single moment was over sung or under sung, overdone or underdone. McKinny hit the Figaro bullseye.

Mafi was an equally winsome Susanna and did much to maintain the buoyant tone of the evening. Mafi evinced a convincing spontaneity while running here, there, and everywhere, always a step ahead with her shifting tactics, confident even when occasionally exasperated. She managed to be pert without being cloying, balancing broad comic action with a grounded naturalness.

Her light lyric soprano was clear and pleasant, responsive to Da Ponte’s text and Mozart’s musical line, and serving as a fine vocal foil to all the other characters (It’s interesting to note that in addition to Susanna’s two arias and several ensembles, she sings in every one of the opera’s six short duets — two with Figaro, and one each with Marcellina, Cherubino, the Count, and the Countess). Mafi’s magical rendition of “Deh vieni, non tardar” suspended time, just as ones hopes that aria will do when it finally gets cued up in the last act. Her technique allowed her to produce an intimate tone that was somehow both airy and full at the same time. The end of the aria was one of the few moments the conductor loosened up her baton a bit and let the sentiment linger so we all could savor the lovely moment.

Not Your Typical Nobility

Countess Almaviva’s heartbreak and disillusionment with her marriage is where the deeper human side of this story lives. Yet this production didn’t present the character as we traditionally think of her: sophisticated and noble, depressed, dejected, and forlorn.

Instead, dressed initially in a hot pink peignoir, this vibrant Countess was game from the get go — frustrated by her husband’s detachment and actively engaged in plotting to win back her dignity. Soprano Marjukka Tepponen brought an animated and forthright determination to the role and contributed actively to the witty comedy. Her lyric soprano had a cool, creamy quality that matched the music well and her top register bloomed beautifully to fill the auditorium. Only a few notes in the most exposed measures of her two arias displayed issues with intonation.

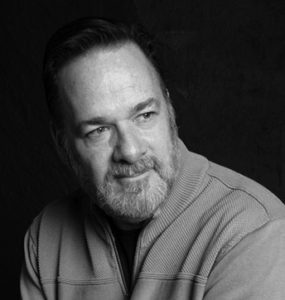

Norman Garrett as Count Almaviva (Photo credit: Sunny Martini)

Norman Garrett was as dashing and likable a Count Almaviva as one could image — tall in stature, aristocratic in bearing, and suave of voice. In service to the production’s emphasis on comedy, he seemed more exasperated than angry at always finding himself outsmarted. In his plea for forgiveness at the opera’s end, it was as if he realized he will never win at this game, so why keep trying? Garrett’s Count was embracing his better self in a gesture that embodied the words engraved in massive letters across the top of the set: “Perdono non merta chi agli altri non da,” a lyric sung by the Countess and Susanna in Act Two that translates roughly to the idea that no one deserves forgiveness who does not forgive others.

One Introvert Among a Palace Full of Extroverts

Olga Syniakova’s Cherubino was, oddly, the one character that didn’t fall in line Seattle Opera’s high comic approach. Her shy Cherubino came off as an introvert to the point of nearly disappearing in the rambunctious energy on stage. This was a surprising interpretation considering all the cross dressing, hiding, flirting, and fish-out-of-water moments written into the score for this lovesick young guy. Vocally, Syniakova was competent, but occasionally her phrasing was choppy, her vowels oddly projected, and her intonation off.

Marcellina and Bartolo were in the capable hands of Seattle Opera regulars Margaret Gawrysiak and Kevin Burdette. They made a funny, stylish couple and skillfully managed the transition from Figaro and Susanna’s frenemies to their family and winning the audience over. The last act character arias for Marcellina and Don Basilio were cut in this production as they often are in order to keep the plot moving as the opera nears its end. Tenor Martin Bakari made Don Basilio a gloriously gossipy and gaudy fop, and Barry Johnson was a hopelessly befuddled but determined-to-get-it-right Antonio.

Ashley Fabian gave Barbarina a flirtatious confidence, and Anthony Webb completed the cast as a dutiful Don Curzio.

Production Elements Had Highs and Lows

The set by Benoit Dugardyn consisted of tall white columns, columns, and more columns revealed as interstitial walls were selectively removed for each act. The payoff came with the spectacular palace hall of Act Three when all the walls were gone leaving a grand open space circled by an array of cornices. One glittering chandelier cast a brilliant reflection in the high-gloss checkered floor.

Prior to this reveal, the anteroom of Act One was an incongruously large, flat room with a few towering columns and huge washed out walls. Considering it was conceived as a storeroom between the bedrooms of the Count and Countess, the room was surprisingly bare—only two or three chairs, one standing mirror, and one dress form. More set dressing (trunks, suitcases, boxes and crates, cabinets, furniture, artwork, hunting gear, etc.) would have added to the stark setting and created possibilities for the characters to engage in stage activity that underlined the action.

The Countess’s bedroom in Act Two would have been improved by a greater emphasis on the placement of the doors to help sharpen the farcical comings and goings. (And a pet peeve of mine: when doors get opened onstage and there’s nothing behind them except “backstage” the audience’s suspension of disbelief breaks for a moment; in a production like this, the set design should encompass everything the audience can see).

The garden of Act Four was a let down: we saw the same columns with two interior walls from the earlier acts added back in, plus three moveable faux pine trees. The two doors we’d seen before were repetitive and incongruous — exactly where they led was unclear, creating confusion about the rapid entrances and exits as the plot reached its climax.

Act Four: set design by Benoit Dugardyn, lighting by Connie Yun, costumes by Myung Hee Cho.

Connie Yun’s lighting provided perpetually happy and bright illumination to the comic goings-on with some nuanced shifts of tint—even the late-evening garden scene was well lit. Myung Hee Cho’s period costumes were well-tailored and amped up the light-hearted vibe with endless swaths of delicious sherbet tones in shiny silk and satin finishes for everyone. There was little differentiation made between the garments of the aristocrats and their servants in this cheery, egalitarian interpretation of the opera.

Peter Kazaras deserves credit for keeping the action moving and aligning the performers with the production’s effervescent tone. Yet there were missed opportunities to expand his initial staging ideas to further enhance the story and enrich the humor. Figaro had little interaction with Cherubino during his famous teasing aria about military service, “Non piu andrai, farfarlone amoroso;” Susanna and the Count’s “Crudel! Perche finora” duet had them stuck in distant chairs most of the time; and the topiary trees on wheels in the last act were hardly used and might have offered some comic payoff as more cleverly choreographed hiding places.

I want to make note of my appreciation of the stylish embellishments added to most of the arias: as with all the other components of the production, they added to the sparkling aura of the evening with a touch of vocal panache.

Categories

Stage Reviews