Seattle Opera has produced a riveting production of the new opera “Blue,” composed by Jeanine Tesori to the libretto of Tazewell Thompson, who also directed. “Blue” shines a searing light on issues of racism, violence, and the loss that result. Everthing comes together for this West Coast premiere to create a gripping, enlightening, and moving experience.

Originally commissioned by The Glimmerglass Festival led by Francesca Zambello (who influenced the creation of the work), “Blue” premiered in the summer of 2019 and has won several awards. A few productions were planned regionally, though some were postponed because of the pandemic; however, Seattle is fortunate to experience this major new opera and hear the singers who originated the two principal roles: Briana Hunter as The Mother and Kenneth Kellogg as The Father.

A Universal Journey from Joy to Tragedy

One powerful attribute of great art is that it can be timely and timeless. “Blue” is that; it tells a story about a specific family in Harlem in the early 20th century while remaining revelatory to everyone everywhere. The family’s generic names, “The Father,” “The Mother,” and “The Son,” underscore their status as archetypes.

Tesori and Tazewell structured the opera in two acts framed by a Prologue and Epilogue that condense selected scenes into a potent narrative around the joyous birth, short life, and tragic death of a young Black man.

The opera opens with a short instrumental prelude as three policemen confront a Black male dressed in jeans and a hoodie. They silently lead him to the police station, where identities blur as he changes into a police uniform and becomes The Father, an “officer of the law” as he later refers to himself. It is here that Tesori’s music feels the most abstract and atonal, using percussive effects and drone-like sounds to elicit a pervading sense of unease.

A Sisterhood of Goodwill

We quickly meet The Mother, who is a restauranteur, and her three Girlfriends, gathered to offer her congratulations and warnings when they hear the news of her pregnancy. They warn her about the risks that “every Black girl knows” of bringing a Black son into this world. The music leaves its initial atonal gestures behind and proceeds to move effectively from natural and humorous musical dialogue between close friends to utterly rapturous measures when The Mother expresses her love for her husband, saying, “Big shoulders that can carry the weight of the world. Big deep voice—I could pitch a tent and live in the body of that voice forever. Big thick lips that, when he kisses me, he takes me to the river!”

Briana Hunter’s vibrant and beautiful mezzo pulsed with emotion and shone with hope through an array of vocal shadings, colors, and dynamics.

The scene closes as the Girlfriends offer beautifully expressed wishes of goodwill for the baby boy. “Scrape the wax off your wings. Soar to the sun. Stand tall before all others, like a lighthouse. Know you are wanted and loved. Let the goodness within you flash a light on the darkened road.” Throughout the opera, Tazewell brilliantly balances natural colloquial language with rich yet grounded poetry in this manner.

New Parents Finding Their Way

After The Son’s birth, the score and libretto continue to move deftly between light, humorous scenes and sections of sweeping lyricism. An overly perky and officious maternity ward nurse—cleverly sung by the high-flying soprano Ariana Wehr—offers the new parents advice to comic effect. In a piece of brilliant symmetry to the earlier girlfriends scene, The Father’s three Policeman pals meet with him to offer their amusing toasts and cautionary parenting tips, welcoming him as a new member of “the daddy club” while watching a football game on television at a sports bar. Camron Gray, Korland Simmons, and Joshua Conyers were perfectly cast as the friends, presenting the scene’s humor and the group’s camaraderie with ease.

Tesori gave the Father soaring music as he tried to express how he felt about his impending fatherhood to his friends, “Like a jockey astride a carousel horse, galloping through a field of stars. A jockey who has just grabbed a brass ring. I feel like the first man on the moon.” Kenneth Kellogg presented a strong stage and vocal presence. Still, he played much of these early scenes in a rather stoic manner, which I think limited his opportunities for bringing nuance of tone and dynamics to the euphoric music.

Teenage Angst and Conflict

In sharp contrast to the upbeat elements of the story so far, the plot makes a sudden leap 16 years in the future, where we meet The Son, now a rebellious and righteous teenager fighting for independence at home and economic and racial justice in society. Tesori and Tazewell drop us right into a high-stakes argument The Son has with his father, one that covers territory familiar to most parents and teens, as well as issues particular to this family around the tensions of being the Black son of a Black cop. “Look at you! Dressed in a blue clown suit. White man’s dog. His lackey. Don’t you know they despise you? Don’t you know, no matter what you do for them, it’s never enough.”

The scene is long and tense, but it ends with a poignant musical epiphany as The Father holds his son and pledges, “I will never let you go. Not tonight, not tomorrow, not ever.”

Kellogg was commanding in this duet, his voice responsive and resonant and his diction and phrasing clear and powerful as he expressed The Father’s anger and frustration. Tenor Joshua Stewart was astonishingly good as the passionate teen, with his clarion voice and youthful physicality conveying the young man’s sardonic worldview. To Tesori, Tazewell, and Stewart’s credit, an operatic tenor expressing the overwhelming angst of a contemporary Black teenager seemed perfectly believable.

Tragedy Strikes, Religion Falls Short

Act two begins with an anguished meeting between The Father and The Reverend, during which we learn a police officer has killed The Son at a protest. The stakes couldn’t be higher as The Father rages about the loss of his son and the grave injustice while The Reverend attempts to lead him beyond his fury and pain to heal through religious faith. Many of Tazewell’s lyrics raise profound and provocative questions about the role of religion. Still, in performance, the scene was overly long and bordered on being didactic as neither character changed the other’s thinking. When two characters begin a scene with differing points of view and then talk (or sing) for about 15 minutes only to end the scene right where they started, you’re in a theatrical cul-de-sac. Gordon Hawkins’ grounded baritone brought grandeur and conviction to The Reverend’s rangy vocal line, and Kellogg was in his element expressing The Father’s new cynicism and resentment, often with understated intensity.

The Grief of Mothers

The Mother’s grief-drenched funeral preparations with her three Girlfriends pulled us over an emotional cliff. The contrast of these women from Act one to Act two was impressive. Their snappy girlfriend gossip of Act one descends into bitter grief and anger at The Son’s death, along with all the other cases where “The uniformed and packing great white hunter” has swatted Black youths, men, and women “down like flies.” What a testament to the versatility of the three women portraying the Girlfriends: Ariana Wehr, Elliana Lewis, and Cheryse McLeod Lewis. Each sang individually with breath-catching conviction of tone and purpose, which blended in a unified chorus of despair. The Mother’s desperate breakdown was searing in Briana Hunter’s hands. “Bring my baby back! Any way you choose, I’ll take him. Take away his hands and feet, but bring him back to me. Bring him back blind. But bring him back to me.”

The funeral scene was somber and spiritual as The Reverend and congregation sang a mix of solos and fragments, with one set-piece, “Somebody, oh somebody,” based on the musical fabric of the Black spiritual, building into a large, complex ensemble. Tazewell crafted gorgeous imagery to send The Son to heaven: “Find him a room near a galaxy burst of stars. He will love the light when he sleeps.”

A Glimmer of Lost Possibilities

The opera seems to end before unexpectedly segueing into the Epilogue—a flashback to an upbeat family dinner the very night the police kill The Son. Here, Tesori and Tazewell revive all the hope we felt in Act one, giving The Mother an endless sequence of playful words and skillful rhymes about the amazing dinner she’s prepared. But the memory fades away as the congregation sings their hymn.

A Brilliant, Unified Score and Libretto

Overall, Tesori’s score has a broad musical appeal that is essentially tonal in feel. The music is majestic and sweeping, yet intimate and personal, with robustly classical elements and nary a trace of any “Broadway sound.” (Tesori composed the Tony Award-winning score for “Fun Home.”) Its palette has nuanced glimmers of American Black musical idioms, but it is no pastiche—the score creates and inhabits its own world and is wholly unified. Most impressive is how the music brings Tazewell’s astonishing libretto to life in a seamless collaboration.

Tesori writes well for classical voices, individually and for the small ensembles. And the orchestration was ideal, rarely drawing overt attention to itself. Conductor Viswa Subbaraman deserves huge credit for the glowing and unified sound of the orchestra.

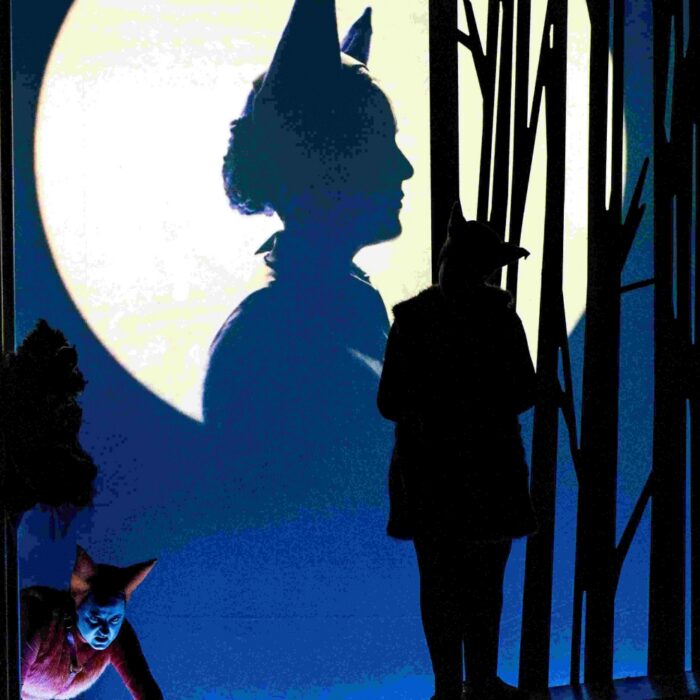

Ideal Production Design

The set, lighting, and costume designs were effectively spare and simple. The towering stark white Harlem brownstones backdrop, set at a skewed perspective, was at once beautiful and provided opportunities for subtle and magical shifts in lighting. Still, it also elevated the story to a timeless and universal status, saying this tragedy could happen anywhere.