Rossini Opera Festival 2022 Review: Le Comte Ory

Flórez & Fuchs Among Highlights in De Ana’s Rendering of Bosch’s Garden Of Earthly Delights

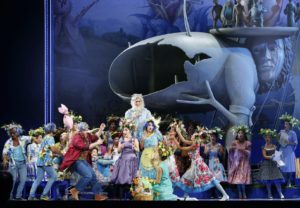

By Alan Neilson(Photo: ROF/Amati Bacciardi)

Pesaro’s Rossini Opera Festival kicked off its 43rd season in splendid style with a presentation of the composer’s “Le Comte Ory” conducted by Diego Matheuz and directed by Hugo De Ana, with a stellar cast which included Juan Diego Flórez, Julie Fuchs and Maria Kataeva.

Not only did it prove to be a magical musical experience, but the imaginative staging was both visually stunning and fun to watch, while De Ana’s intriguing contextual framework, based around Hieronymus Bosch’s triptych “The Garden Of Earthly Delights,” was cleverly fashioned to allow for a variety of interpretations.

De Ana Offers Up A Variety Of Interpretations

Bosch’s well-known triptych, painted between 1495 and 1505, appears to be a traditional telling of Man’s fall from grace and descent into Hell. In the first panel, God presents Eve to Adam, who possesses a notably lustful gaze. The central panel depicts Man, following his expulsion from Eden, in the false paradise of the garden of earthly delights, in which men and women abandon themselves to amorous activities, taking pleasure in their short-term happiness. It is, however, a sinful path, one which leads directly to Hell, which is represented in the third panel.

Certainly, there are aspects of this which can be directly related to “Le Comte Ory.” The general tenor of the opera, specifically illustrated by Ory’s lustful nature and general behavior, and his pursuit of Adèle, as well as Isolier and Adèle’s mutual lust, could easily fit into the false paradise depicted in the central panel. The problem, of course, is that the opera is a comedy, Ory’s attempts at seducing Adèle fail, and, importantly, no one ends up in Hell. Yet, for all this, De Ana’s reading held together well, for it was a presentation which allowed one to engage with the drama on different levels, and offered numerous pathways around this supposed impasse.

Bosch’s work, for example, can be reinterpreted in a completely different way. Rather than a warning against the sin of lust, the garden can be seen as set at a time before the flood where pleasures are taken in a state of innocence, when Man is still at one with nature, or alternatively at time when innocence itself has been reborn. The fact that Bosch’s Hell does not depict punishment for the sin of lust, but does so for gamblers, musicians and priests adds weight to such an interpretation.

Of course, maybe De Ana intended no direct link at all, but simply wished to present a series of images taken from the triptych to conjure up a surreal canvas upon which the drama could play out, and which would operate on an unconscious level.

A more complex view, and one which is supported by the staging, is that it was presenting the three panels in reverse order. The men have gone to fight in the crusades, leaving the women alone in a frustrated and dissatisfied state, which De Ana captured brilliantly by having the women twittering and flapping around in a state of high agitation every time a man appeared, like chickens when a cockerel arrives. It is a state he likens to Hell, which he affirms by having a giant model of the ‘tree man’ from the third panel dominate the stage. Ory then arrives by emerging from an egg as found in the central panel, and his easy, lustful behavior ultimately has a liberating effect, so that in the final scene, the stage was populated by couples in amorous embraces. Paradise has been reinstated, innocence has returned, guilt has disappeared.

To be fair to De Ana, he makes no claim for any specific interpretation, allowing the audience to see it in their own way, and the fact that all readings were possible made it an intriguing and satisfying experience. However, it was far more than that, it was also a dramatically coherent and amusing presentation, which had the audience laughing out loud on occasions.

De Ana also acted as the scenographer and costume designer. His staging used visually captivating and aesthetically pleasing projections of scenes, as well as large-scale models of the animals and objects, from Bosch’s triptych. They were not always used rigidly to denote any specific meaning, but rather to create a generalized impression. Often, they were supported by bold clear blue lighting, designed Valerio Alfieri, which called to mind Dali’s surrealist paintings, which in themselves were clearly influenced by Bosch.

His costume deigns were mesmerizing. They were colorful, imaginative and often flamboyant, especially in the case of the chorus, and added to the aesthetic brilliance of the staging. There was also plenty of humor in their design: the incongruity of having Flórez dressed in a blue nun’s tunic with a white headdress, while wearing bright red and yellow training shoes was absurdly funny.

De Ana was also attentive to the pace of the drama, often having plenty of onstage movement in order to promote its energy and comedy, such as having a few dinosaurs invade the stage at the end of Act one, allowing Ory to show off his shooting skills, in an obviously slapstick manner. It was an approach that successfully allowed the work’s quieter passages to gain prominence.

Delightful Trio

The whole cast was truly excellent, and not just for their singing. They Immersed themselves fully in their characters and engaged completely with the director’s ideas, and displayed brilliant comedic skills.

Ory is a role with which Flórez is very familiar, which he illustrated in the detail he was able to bring to his performance. Facial expressions and gestures were expertly delivered with precise timing to maximize their impact. Even the way he walked around the stage was something he has developed over time, so as to guarantee laughter. His singing sparkled throughout the performance, with his vocal beauty, secure phrasing and seamless passaggio particularly impressive. Recitatives were cleverly inflected with humor to capture the absurdity of his dissembling, or his mock outrage.

Fuchs was no less impressive in her portrayal of La Comtesse Adèle who, in the early stages at least, convincingly managed to steer the difficult line between remaining chaste and giving expression to her strong desires. Her Adèle, however, was an impulsive character, and had no intention of remaining chaste for long. She was happy to find herself in the garden, and sought every possible opportunity to be the arms of Isolier. Such is Fuch’s stage personality and the quality of her singing, she is able to dominate the stage with ease, which allowed her to achieve parity with Flórez’s Ory. Her sense of stagecraft perfectly complemented Flórez’s, so that scenes involving the two of them came wonderfully alive, fizzing with energy, and on many occasions with laughter. Her singing was beautifully moulded to develop her character, in which she often exaggerated her phrasing or her coloratura to infuse it with humor, with suggestive ambiguity or desperate denial.

Comte Ory’s page Isolier is a character in the thick of the action. Always around, he not only serves Ory, but as his rival for Adèle is constantly plotting against him. Mezzo-soprano Maria Kataeva, cast in the role, produced a strong performance, skillfully capturing the young man’s ardor, and the comedy of his relationship with Ory, who treated him as irritant of no consequence, pushing him aside without thought. It was also an accomplished singing performance, one in which the tonal beauty, strength and versatility of her voice impressed, along with her ability to shape her presentation to define her character.

The opera is comprised of many ensemble numbers, which without exception were superbly rendered. It was the Act two trio “A la faveur de cette nuit obscure” between Ory, Adèle and Isolier, however, which really stood out for its sensitive, polished presentation. Flórez’s beautiful singing was coated with expectation and ardor, Fuchs’ voice veered between fear and arousal, while Isolier singing was alive with expectation as his passions rose. Their voices complemented each others wonderfully, in what is also a testament to Kataeva’s performance. The staging was equally sensitive with their three bodies delicately caressing each other, which added a degree of tension to the scene. All abruptly changed as the trumpets announced the arrival of the crusaders, causing their voices to race off in different directions, with Flórez’s tone hardening as his anger rises, while Fuchs’ coloratura takes to the wing, as emotions abruptly swing.

Solid Supporting Players

Bass Nahuel Di Pierro was cast as Ory’s put-upon Le Gouverneur. Possessing a strong, clear, resonant voice, he produced a well-defined character, who was clearly fed up with looking after his wayward charge. His well-declaimed recitatives displayed depth and versatility, and his aria “Veillier sans cesse” was neatly rendered, but it was his Act one, scene five realization that he had finally stumbled upon Ory which displayed his talents most clearly: accompanied by the chorus, he showed off his lyrical beauty, while voicing his growing awareness that Ory was close at hand.

Baritone Andrzej Filonczyk made a good impression as Ory’s companion Raimbaud, in which his semi-drunken toast “Dans ce lieu solitaire” to Adéle’s absent brother, sung with the accompaniment of Ory’s disguised men, was his standout contribution, allowing him to display his energetic, lyrical, versatile voice to good effect.

The evergreen mezzo-soprano Monica Bacelli was cast as Dame Ragonde, producing a high energy and expressively convincing performance as the castle housekeeper.

In the minor role of Alice was mezzo-soprano Anna-Doris Capitelli, who produced a well-sung flighty performance as a simple village girl.

Matheuz elicited an energetic performance from the Orchestra Sinfonica Nazionale della RAI, which was rhythmically strong, vibrant and contained a pleasing forward momentum which allowed Rossini’s lively melodies to bloom, whilst always remaining sensitive to the dramatic twists of the plot. The overall piece was clearly contoured, although textural and dynamic contrasts were not fully exploited, possibly compromised by the music’s energetic thrust. The balance between all the musical forces was excellent: there was barely an instance in which any single element was overwhelmed, making the large choral scenes detailed as well as powerful.

The Coro del Teatro Ventidio Basso under the guidance of Giovanni Farina was in excellent voice, singing with sensitivity and energy, whilst achieving a pleasing balance between voice types. Their acting was also of a high quality.

Overall, this was a stunning production which worked well on every level. It was a fabulous musical experience which included top quality singing. The staging was visually strong, with imaginative scenery and colorful costumes, whilst the underlying context created by De Ana was inspired and worked brilliantly. Moreover, it all came together perfectly, ensuring the audience was kept amused and engaged throughout.