Palazzetto Bru Zane 2017-18 Review: Les P’tites Michu

André Messager’s “Babes in the Bathtub” Rarity Given a Riotous Revival in Paris

By Jonathan SutherlandLooking like a doppelgänger of Sir Adrian Boult, Hercule Poirot or the Monopoly Man, André Charles Prosper Messager (1853-1929) was an extraordinary musician whose memory, at least in Anglophone countries, has sadly slipped into oblivion. It is hard to believe that this immensely accomplished pianist, organist, composer, director of both the Opéra de Paris and the Royal Opera House Covent Garden and conductor of the world premieres of “Pelléas et Mélisande”, “Louise,” and “Grisélidis” (Massenet) could have been catapulted so quickly into the musical Milky Way. The prodigious musician was particularly close to Gabriel Fauré and the two composers often travelled together to hear performances of Richard Wagner. They even jointly wrote a cheeky piano spoof for four-hands of “Der Ring des Nibelungen.” Lest one wrongly conclude that such Anna Russell-esque sacrilege was typical French anti-Teutonic snootiness, both Fauré and Messager were committed proselytizers of the Gesamtkunstwerkmeister, with the latter conducting the first performance of “Parsifal” in Europe outside Bayreuth in 1914.

Messager’s private life was no less remarkable with an endless succession of mistresses including the celebrated soprano Mary Garden. The choir-organist of Saint-Sulpice and conductor of the Folies Begère had a Proteus-like personality encompassing religious radical and unrepentant roué and was as fecund in composition as he was in seduction. Messager is credited with having written 30 opérettes, 8 ballets (including the still performed “Les Deux Pigeons”) a symphony, numerous instrumental works and dozens of songs. Unlike Sir Arthur Sullivan who was always whinging that his musical genius was wasted on popular trifles with WS Gilbert, Messager believed that his natural talent was in writing music for opérettes. His most enduring opéra comique “Véronique,” first staged in 1898 was such an international success that having invented “Pêche Melba” for Dame Nellie, Escoffier created a new dish “Sole Véronique” in its honour. Fortunately there was nothing fishy about “Les P’tites Michu” which had a triumphant debut at the Théâtre Bouffes-Parisiens the previous year. The London version in 1905, sung in English and unsurprisingly called “The Little Michus,” ran for over 400 performances.

An Overlooked Work

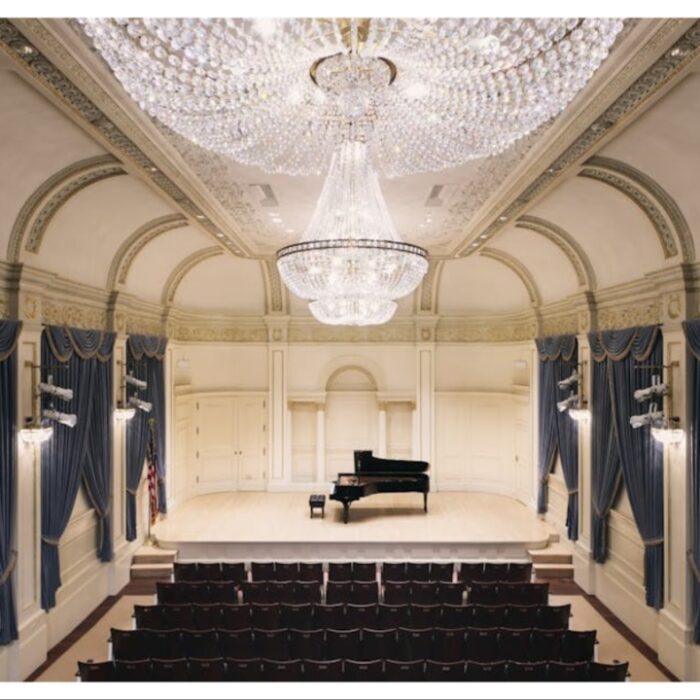

It says much for the wide-ranging scope of the activities by Palazzetto Bru Zane that the organization created to promote romantic French music from 1780-1920 does not restrict itself to highbrow operas by Gounod, Massenet or Meyerbeer. It is equally prepared to champion popular music of the period and has already staged such esoteric bon-bons as “Les Chevaliers de la Table ronde” and “Mam’zelle Nitouche” by Hervé. In co-production with Angers Nantes Opéra and the Compagnie Les Brigands, “Les P’tites Michu” was presented in Paris at the exquisite 560 seat Athénée Théâtre Louis-Jouvet situated a short pas de deux from the very grand Palais Garnier. Interestingly this absolute gem of a theatre (then called the Comédie-Parisienne) was the venue for the premier of Oscar Wilde’s scandal-ridden play “Salomé” in 1896.

The plot of “Les P’Tites Michu” is as light as one of Escoffier’s celebrated soufflés and has precious little depth although there is occasional social satire reminiscent of Hervé. Messager was so delighted with the libretto by Albert Vanloo and Georges Duval he exclaimed “the gaiety of the subject seduced me” and snapped out of a recent depression caused by the failure of “Le Chevalier d’Harmental” and tossed off the score in three months. The partitura not only mirrors the pétillant rhythms of Offenbach or Gilbert & Sullivan, but typical of Messager, has sections of unexpected lyricism such as the graceful 6/8 Romance “Vois-tu, je m’en veux.”

The plot of “Les P’tites Michu” begins during the Reign of Terror in 1793 when due to his wife’s death during childbirth and anticipating imminent arrest, the Marquis d’If entrusts the care of his newly born daughter Irène to the kindly Michus. The money for the foundling’s upbringing enables the Michus to set up a thriving cheese business at Les Halles in Paris. The Michus also have a daughter the identical age and appearance as la petite Irène. Similar to “Il Trovatore” but without the gruesomeness of a baby boy hurled onto a burning pyre, the identity of the two infants is confused when Monsieur Michu plops the babes into a bath together and realizes that naked, there is nothing to distinguish one soapy tot from the other. The stage action occurs 17 years later when the Marquis, now Général des Ifs in Napoleon’s army, returns to reclaim his daughter and offer her in marriage to the officer who saved the his life in battle, Captain Gaston Rigoud. The scene where the General walks in to find two identical girls could have been from a farce by Feydeau or Philip King. The teenagers, suitably reverse-named Blanche-Marie and Marie-Blanche, believe they are twin sisters, as does an enamored suitor and employee of the Michu’s, Aristide, who is in love with one his boss’s daughters except he doesn’t know which one. The confusion is resolved when Marie-Banche, clearly more bourgeois street-smart than the inherently ditzy aristocratic Blanche-Maire, hits on the idea of dressing her soi-disant “sister” in identical clothing and coiffure to that of the marquis’ deceased wife as shown in a family portrait. The likeness is unmistakable and the marquis is overjoyed at finding his true daughter. All ends happily with Blanche-Marie marrying Gaston and Marie-Blanche content to be Aristide’s wife and continue the booming family cheese business at “La Poule aux Oeufs d’Or.”

Not the Musical Arrangement the Work Deserves

The musical arrangement by Thibault Perrine reduced Messager’s original score to nine singers and twelve musicians. Whilst this worked well for the vocalists with superfluous schoolgirls and dames invitées duly culled, the effect on the instrumentation was less felicitous. Messager was a highly accomplished orchestrator and his trademark multiple sonorites, especially noticeable in works such as “Véronique” and “Madame Chryanthème,” were lost in this impuissant truncated instrumental version. That said, Pierre Dumoussaud led “les douze” with plenty of verve and élan. In the interests of dramaturgical tightness there were several chorus deletions such as “À la boutique! À la boutique!” but more significant cuts in the spoken dialogue. As the text is hardly of Molière magnificence, no real damage was done, although diction throughout tended to be garbled and articulation poor.

Pastel Pink & Baby Blue

Rémy Barché’s mis-en-scène kept the action brisk and easy to follow and the pastel pink and baby blue stage designs with retro touches by Salma Bordes fitted the innocence of the work admirably. Oria Steenkiste’s costumes featuring matching short skirts and T-shirts for the twins could have come straight out of “Happy Days” or an NFL cheerleader’s wardrobe. The childish illustrations and projections by Marianne Tricot, many with bubbles, gurglings and other bath-like associations, were charming.

The role of the General’s factotum Bagnolet was sung by Romain Dayez with Figaro-ish nous and Don Basilio conniving. There was a curious “Cage-aux-Folles”-ish characterization and an annoying tendency to shriek rather than speak, but the Offenbach-ian “Rataplan” chorus had plenty of punch and strong projection. The formidable schoolmistress Mademoiselle Herpin was an ultra-rightwing martinet cum dominatrix not averse to flirting with the visiting General. Brandishing a menacing baton and attired in buttock-clinging canary yellow or Schiaparelli-cerise ensembles, the part was amusingly acted and convincingly sung by mezzo Caroline Meng. Boris Grappe huffed and puffed as the daughter-deprived Général d’If and was vocally more booming buffo than solid basso. The “Non, je n’ai jamais vu ça” rondo could have been Dr Bartolo in military mode although the “D’un benet, d’un ane, d’un sot” patter song was well articulated.

As the babies in the bath bungler, Damien Bigourdan overacted to such an outrageous degree Michu père was no longer a music hall stereotype but a grotesque caricature. He also looked like a younger version of Gordon Kaye as René in “‘Allo, ‘Allo.” There was a tendency to go for cheap laughs and screech or wail most of the lines as if having swilled too much Calvados at breakfast. In the spoken dialogue, Bigourdan’s accent changed at whim and vocally the actor was only average. Marie Lenormand as his more collected wife displayed much more musicality. The handsome Captain of the Hussars was sung by Philippe Estèphe who was a mellifluous Gaston with an arresting upper register which included solid F naturals on “je l’aime” in the “c’est la fille du Général” trio. “Quoi, vous tremblez ma belle enfant” was sensitively phrased and the timbre of the voice consistently pleasing.

Scene Stealer

The most impressive performance came from Artavazd Sargsyan who was dramatically credible as the simple-natured Aristide in love with both Michu filles. Possessing a light, forward placed tenore di grazia, Sargsyan showed stylish phrasing and a natural affinity for the opérette idiom. “Blanche-Marie est douce et bonne” was sung with tasteful legato whilst the allegro “Comme une girouette mon coeur tournait” displayed some beautifully placed F naturals, admirable diction and innate musicality.

Two Sisters

The sisters were suitably similar yet with nuanced character differences which became important as the story unfolded. With a slightly higher tessitura, Blanche-Marie was sung by Anne-Aurore Cochet and Marie-Blanche by Violette Polchi who was the superior vocalist. She also gets more to sing. The catchy 3/8 duet “Blanche-Marie et Marie-Blanche” in major thirds was a peppy foot-tapper. The ostensibly pious “Prière à St-Nicolas” with the text projected above in a schoolgirl’s cahier as the loving twins were suddenly deadly rivals in the battle to become Irène d’If, was extremely amusing. Marie-Blanche’s “Vois-tu, je m’en veux” romance showed a warm timbre and impressive legato. The rollicking “On peut chercher en tous pays” tribute to Les Halles testified to Polchi’s formidable mid-range and chest voice. An interpolated G natural fermata leading to lower E natural on “je commence” during the Minuet maquillage scene was an unexpected display of vocal bravura.

Non-French speakers would have had a difficult time Chez Michu, but the œuvre promoted by Palazzetto Bru Zane was “delightful, delicious and de-lovely” as Francophone Cole Porter once enthused. It showed that excellence can be found as much in the fun and froth of opérettes as in the grand sentiments of Massenet or Meyerbeer. This was a sparkling evening rightly reviving the reputation of its protean Parisian creator.

André Messager vit encore!