Page to Opera Stage: Goethe’s ‘Faust’ Through Berlioz, Gounod, & Boito

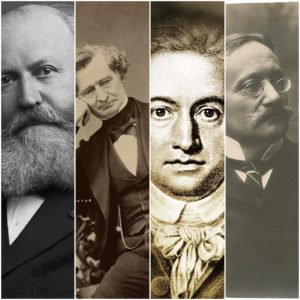

By Carmen Paddock“Page to Opera Stage” looks at stories – real-life or fiction, old and new – that have inspired operas, and the ways these narratives have been edited and dramatized to fit a new medium. This week, the focus is Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s two-part magnum opus “Faust” and three operas – Berlioz’s “La damnation de Faust,” Gounod’s “Faust,” and Boito’s “Mefistofele” – that draw inspiration from Goethe’s particular reworking of the medieval legend.

A deal with the devil is a tale as old as time. The legend of a scholar who trades his soul for unworldly power, universal knowledge, and romance across time and space dates to medieval morality plays, with even increasingly secular generations finding fascination in its examination of faith, morality, and known limitations. It is a story that will likely be adapted and re-adapted for eternity, but Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s two-part reimagining – half poem, half play – remains one of the best known.

The German literary titan spent over 57 years on his tale of science and religion, sin and redemption. “Faust Part 1” was published in 1808, “Faust Part 2″ completed in 1832 and published after Goethe’s death the same year, and an unpublished draft referred to as the “Urfaust” was begun in the early 1770s.

Goethe’s work sits at a strange literary intersection between a stage play and an epic poem. “Part 1’s” plot, characters, and action most suit a traditional drama, but its form does away with traditional acts and scenes; by contrast, “Part 2” sticks to a traditional five-act format but includes almost-unstageable transitions and effects.

While Goethe wrote much for the stage and both parts of “Faust” are divided into theatrical dialogue, many believe it an epic poem unintended for performance due to its almost twenty-hour length and the scale of the stage effects required. This has not stopped theatres from staging the work either in its entirety or in abridged versions – including one version adapted by Goethe himself for the Weimar State Theatre. These undertakings, however, are infrequent in comparison to the operas that have been inspired by Goethe’s mythic reworking.

Goethe’s “Faust” is notable for one addition and an ending at odds with many previous retellings. The second half of “Part 1” is largely concerned with the young peasant girl Margarete/Gretchen, an original Goethe creation for Faust to love and leave. And while Goethe was not the first to redeem Faust at the conclusion of “Part 2” – in the final judgment, he only loses half his wager with Mephistopheles – this salvation stands in marked contrast to Christopher Marlowe’s earlier seminal version.

Of the thirty-odd operas based on the Faust legend – with several of these inspired by Goethe’s particular spin on the tale – three deserve special mention in relation to Goethe’s themes. Hector Berlioz’s “La Damnation de Faust” arguably stays closest to Goethe’s atmosphere and characterizations, albeit with a twist at the end. Charles Gounod’s “Faust” is at least one adaptation removed from Goethe’s material, continuing the tale’s ever-mutating tradition. Lastly, Arrigo Boito’s “Mefistofele” is the only opera among these to take inspiration from “Faust Parts 1 and 2,” keeping both the devil’s daring entry and the fate Goethe’ intended for his antihero.

The Unholy Art

As with Goethe’s play, the ambition of its creator and a lack of adherence to theatrical stylings define Berlioz’s 1849 opera, which premiered at Paris’ Opéra-Comique to a confused, lackluster reception that has been re-evaluated in recent generations. “La Damnation de Faust” does not have an act structure, instead moving fluidly through dramatic, expansive, supernatural scenes – mirroring Goethe’s “Part 1.” The opera’s vast scale – calling for a massive orchestra, multiple choruses, and fast-moving magical tableaus – has given it an equal life in concert as in fully-staged productions.

Out of the three, Berlioz is most concerned with the titular scholar, who almost never leaves the stage. The taxing role holds sole focus for the first four scenes as he outlines his spiritual frustration with his physical and mental limitations. When the devil arrives, his disillusion is palpable and the deal is met with a believable lack of hesitancy.

Even Marguerite’s fate feels like an afterthought. The abandoned lover is not seen again after Faust leaves her, and Méphistophélès relays her fate in narration. A single line of regret is spared in Faust’s Scene XVIII ride into the abyss, but an invocation to nature two scenes prior makes it clear that Faust will press forward in his quest for knowledge and not turn back in regret. He rides on to his bitter end.

Marguerite

Gounod’s “Faust” – which premiered in 1859 at Paris’ Théâtre Lyrique – is the more well-known Goethe adaptation. Its immediately successful reception has continued to the present day. However, the case can be made for his adaptation hewing more closely to the play “Faust et Marguerite,” written by his librettist Michel Carré. Carré’s play and later libretto took several of Goethe’s inventions – notably, Marguerite’s presence and several character names – but reshaped secondary character relationships and Faust’s own pact with the devil.

For instance, Goethe’s minor student Siébel becomes Marguerite’s young admirer and confidant in Gounod, and Faust emphasises his desire for youth and love over anything else Méphistophélès has to offer. When the devil offers him riches, glory, and power, he scorns them all for “un tresor qui les contient tous… la jeunesse” (“a treasure that contains them all… youth”). Once Méphistophélès conjures an image of Marguerite, Faust’s soul is sold.

In some perspectives, this quest for youthful romance cheapens the tale. But perhaps the quest for youth – a task impossible for all regardless of education or repute – is more immediately and universally recognizable than is the quest for natural or supernatural knowledge. Gounod’s version certainly loses no poignancy, especially in its principle framing of Marguerite. Her faith, foibles, and struggles sit at the heart of this retelling, and focusing on her relationship with Siébel, neighbor Marthe, and brother Valentin create an intimate look at a life gone unfathomably, unfairly wrong. With her agency compromised at every turn, her fate still breaks audiences’ hearts today.

Gounod’s “Faust” may be the most suited for the theatrical medium – and not just in terms of its distinct French Grand Opera stylings and endlessly catchy melodies. While it takes the most liberties with the title everyman-turned-antihero’s motivations, its sympathies lie with the victims in Faust’s wake – the external rather than internal consequences. Marguerite’s salvation is well-earned catharsis.

A Devilish Wager

Many have (quite unfairly) looked down on Gounod’s “Faust” since its creation due to its thematic liberties and “easy” tunes. Among the naysayers was Arrigo Boito, who sought a quasi-Wagnerian treatment of the legend in direct opposition to the French composer’s. Boito wrote his own libretto, taking much literally from Goethe and translating it into Italian. “Mefistofele” premiered in Milan in 1868; an initially cool reception warmed after a revised version was performed in Venice in 1876.

Boito is the only composer of this group to open with Goethe’s second prologue: Mefistofele’s wager with Heaven that he can win Faust’s soul. As befits the title, the devil is the opera’s central character, almost always on stage and narrating his inner thoughts as Faust, Margherita, and “Part 2’s” Elena of Troy insert their own perspective in arias and duets. But condensing Goethe’s maddeningly dense work into two and a half hours skips much of “Part 2’s” metaphysical and theological facets in favor of his historical romance. However, his ending hews closest to Goethe’s intentions, as will be discussed below.

The Reckoning

The three operas are remarkably separate from each other tonally and musically, but what sets them apart – notably in relation to their source material – are distinct endings for their central philosopher. Berlioz and Gounod end their tales after the death of Marguerite (Goethe’s “Part 1”), and Faust is explicitly or implicitly damned to hell because of his bargain – not to mention his culpability in his lover’s madness and murders. For a dramatic and modern moral standpoint, these endings satisfy – he made his deal, and letting the young woman he victimized find peace while he pays restores a sense of justice to the operatic worlds.

In Gounod, Marguerite calls on the angels for intercession and vehemently rejects Faust’s rescue efforts in a dramatic trio; Faust seems as condemned by her unending faith as by his own actions.

Berlioz’s ending is particularly brutal for the misguided philosopher. As Marguerite faces execution he is dragged straight to hell, and the demons fall silent at his demise. The bargain Méphistophélès struck is an empty promise and a cruel trick.

These endings are the antithesis of Goethe’s conclusion, which sees Faust saved as he recognizes God as the source of true bliss. However, they make sense if ending the story at “Part 1” – Faust needs an ending, and salvation is not a dramatically compelling option at this point in his narrative. In adapting “Part 2” as well, Boito is the only one of these three composers that retains Goethe’s intended ending, as Faust turns back to the angels in the realization that his loves and learnings will not bring him the same meaning that God will. The climatic loss for Boito’s confident title character is satisfyingly humbling – the devil brought low by hubris, outdone in his underestimation of humanity.

Like in Goethe, Marguerite/Margherita is saved in all three versions, welcomed by a heavenly chorus at the close of her opera or section. It is, however, interesting to note that her salvation was an afterthought in Goethe; the intercession of heaven was not present in his “Urfaust” draft, which ends “Sie ist gerichtet!” – “She is judged (condemned)” for the death of her mother and child. However, by the time “Part 1” was published this was reversed (“Sie ist gerettet!” – “She is saved!”). Perhaps over three decades of work on Gretchen’s story made grace the only option.

Prior to his prologue in Heaven, where Mephistopheles dares God to wager Faust’s soul, Goethe inserts a small metatheatrical scene between a poet and a theatre manager. The two bicker about how best to present a drama:

POET

You do not feel, how such a trade debases;

How ill it suits the Artist, proud and true!

The botching work each fine pretender traces

Is, I perceive, a principle with you.

MANAGER

Such a reproach not in the least offends;

A man who some result intends

Must use the tools that best are fitting.

Reflect, soft wood is given to you for splitting,

And then, observe for whom you write!

As the manager proceeds to catalog all the ways in which an audience may not be ready for the loftiest, densest drama, it is as if Goethe were aware his two-part masterpiece would find the best home on the page. In this same way, Berlioz, Gounod, and Boito take their common Faustian reference point and use their own unique, best-fitting tools to shape the stories they want to tell. Like Goethe’s poet and later his philosopher, they found and shaped their truth in the legend – but no devils were (likely) engaged in the process.

Quotations from Goethe’s Faust are from the Bayard Taylor translation, available at Project Gutenberg.

Categories

Special Features