![L’Enfant fantasy [Martha Benedict]](https://operawire.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/LEnfant-fantasy-Martha-Benedict-300x200.jpg)

Pacific Opera Project 2020 Review: Gianni Schicchi & L’Enfant et les sortileges

The Puccini-Ravel Double Bill Connects In More Ways Than Meets the Eye

By Gordon Williams[Credit: Martha Benedict]

For the first production of their 10th anniversary season, Los Angeles’s Pacific Opera Project chose to pair two one-act operas, Puccini’s late comic opera “Gianni Schicchi” with Ravel’s magical “L’Enfant et les sortilèges.” The performance took place at Thorne Hall at Eagle Rock’s Occidental College.

Pacific Opera Project (POP) claims that this is the first time these two works have ever been paired (“as far as we can tell”) and story-wise there is a world of difference between the earthy comedy of “Schicchi” and the enchantment of the Ravel. However, both works were begun in the same year, 1917 (“Schicchi” completed in 1918; “L’Enfant” in 1925) and it was fascinating to hear and compare Puccini and Forzano’s Italian and Ravel and Collette’s French responses to the expanded tonality of the period.

Most Perfect Opera

In his Director’s Note in the program booklet, Josh Shaw, POP’s Co-Founder and Artistic Director, praises “Gianni Schicchi” as “the most perfect opera in all the repertoire.” He may well be right. Certainly, this production highlighted why it is so good – a clever balance between lyricism and action, brilliant management of a huge, diverse cast, and genuine humor. What you find in “Schicchi” is not the outdated operatic humor that Peter Brook mocked in his book, “The Empty Space,” but opportunities for humorously endearing characterization and genuinely funny action.

Much of the humor of this production can be credited to Josh Shaw’s marvelous direction of crowd movement and encouragement of singers’ characterizations. The sight of the ensemble ransacking the house of the recently-deceased Donati to find his will was genuinely desperate and funny.

But there were wonderful character details as well – Tom Sitzler as Simone (now head of the Donati clan) even sang with cigarette drooping out of his mouth.

The depiction of minor roles, such as Danielle Marcelle Bond’s Ciesca and Jared Daniel Jones’ Marco, was excellent, as also a marvelously stuffy notary, Amantio played by baritone Peter Barber.

Tenor Jonathan Matthews’ Rinuccio, in love with soprano lead Lauretta, provided a refreshing lighter tone to the multiple vocal colors of POP’s ensemble.

There was a real sense of suspense as contralto Sharmay Musacchio as Zita informed the Donati family distraught at the idea they may have been disinherited, that there was one person who could help them – Schicchi, universally disliked.

And Tiffany Ho as Lauretta made her delivery of “O mio babbino,” the opera’s one-detachable number, the show-stopping center of gravity that it is meant to be. If there was one false note it was her fake sobbing halfway through, undercutting her own otherwise beautiful delivery and clashing with the lyrical poignancy that allows the rest of work’s humor to shine. The sob could easily be cut.

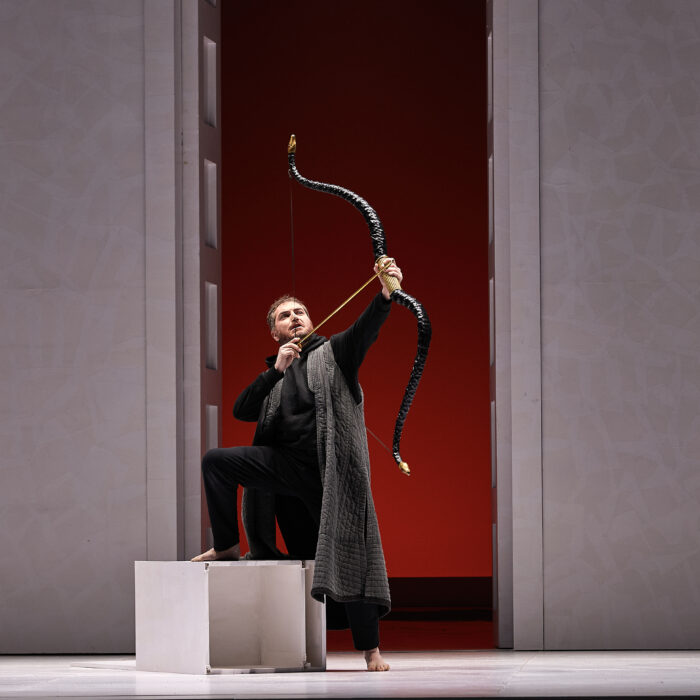

As Schicchi, E. Scott Levin was, as so often, one of the great delights of the presentation. Dressed by Maggie Green almost like a gangster, he was, you could say, to quote the old expression, “as flash as a rat with a gold tooth.” Levin simply commanded the stage, providing an atmosphere of palpable conjuring as he described the ruse by which he would rejig Donati’s will so that everybody could benefit.

His use of a fake voice as he impersonated “Donati,” whose actual body had been shoved into a cupboard, was well-judged. There was a real chill when he dropped into his natural bass-baritone to deed himself Donati’s mansion, mill and mule.

For this occasion, Pacific Opera Project assembled a 55-piece orchestra. It was led flawlessly by conductor Josh Horsch but was perhaps not musically prominent enough, seated to the right of the set with only a few instruments slightly visible. There are decent-sized orchestral passages in the Puccini and of course, a major selling point of Ravel is his orchestration. This deserved to be heard to greater advantage than was possible with the orchestra hidden half-way offstage. On the other hand, there were compensating benefits.

It was possible to concentrate on the excellence of vocal ensemble and appreciate “Schicchi’s” straight-play kind of energy and the cast’s creation of fantasy in “L’Enfant” out of what was essentially a realistic setting. And who knew that Ravel’s work demands a large orchestra, without prior study beforehand? The work’s opening fourths and fifths were effectively archaic without the second oboe. In other moments it was obvious that the score had been well-arranged.

The Link

In Josh Shaw’s conception both these operas are linked by being seen through the eyes of Gherardino, the youngest member of the Donati clan. It is 1955 and Shaw imagines that the young boy in “Schicchi’s” Florence goes home to France with his family, and there, in a tantrum, torments all the toys, household items and denizens of the family garden to such an extent that they take revenge on him.

But more: Gherardino sees in all these “objects” the relatives he has only recently seen at Donati’s deathbed. Thus, some clever role doublings after interval.

Joel Balzun, Betto in “Gianni Schicchi,” is a wonderfully hysterical Clock come to life in “L’Enfant.” Robert Norman, Gherardo in the earlier work, is a hilariously pugnacious teapot. Sharmay Musacchio who played “Schicchi’s” Zita and E. Scott Levin the title role in the first half have their comic moment as Ravel’s two cats mewling and meowing their way through the comical cat duet.

Michelle Drever conjured a spectacular sense of Fire with her clean, clear coloratura. Kimberly Sogioka made up for the minuteness of her role as Gherardino in “Schicchi” by carrying the lion’s share of the load incarnated as Ravel’s “Enfant.” She also provided this work’s particular center of gravity in her delivery of the child’s “Toi, le coeur de la rose,” but of course in “L’Enfant” she delivers this moment of gravity amid some extremes of childish hysterics.

Shaw basically used the same set for “L’Enfant” as he had for “Schicchi,” the only exception being an opening-up to reveal the garden in Ravel’s second scene. Donati’s bedroom and deathbed essentially became Gherardino’s bedroom. It was quite some achievement on behalf of the creative team and cast to turn this realistic 1950s domestic scene into Ravel’s magical world but that’s what happened.

At first glance, “Gianni Schicchi” and “L’Enfant et les sortilèges” might not seem to go together. There are similarities – elliptical melodies, a central vocal number, for instance – but overall these two works did what they would do in a well-programmed concert: different visions from 1917, they spoke interestingly to each other.