Pacific Opera Project 2019-20 Review: La bohème aka The Hipsters

An Increasing Tradition That Brings Out the Intimate in Puccini’s Masterpiece

By Gordon Williams(Photo credit: Martha Benedict)

“La bohème aka The Hipsters,” Pacific Opera Project’s version of Puccini’s most famous opera, has become a regular holiday-season feature of Los Angeles’s opera calendar. This year’s production is the company’s fifth. Staged at the 1912-vintage Highland Park Ebell Club, POP updates “La bohème” to present-day Highland Park, which these days has a large population of young hipsters, hence the re-titling of Puccini’s work.

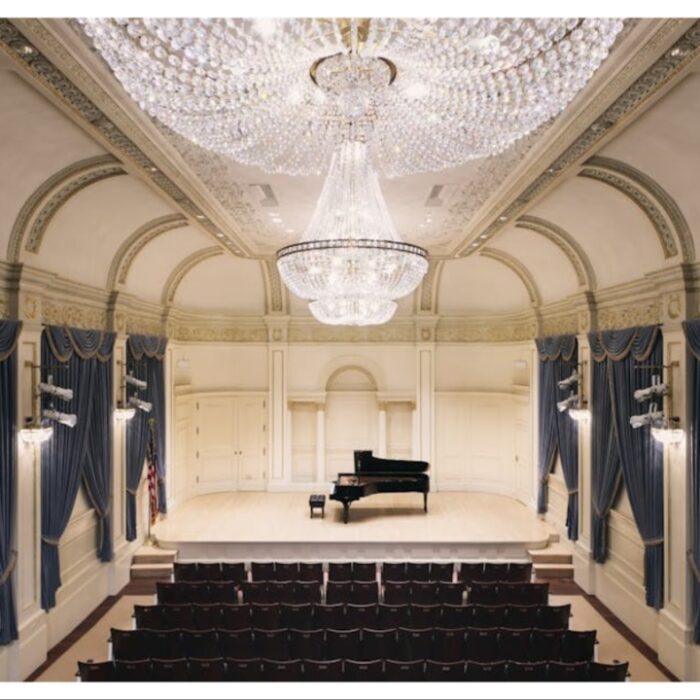

POP’s theatrical space is basically a cabaret. Not far off North Figueroa Avenue and its wine bars, audience-members sit at tables where they, too, may eat and drink. Does such informal atmosphere work for Puccini’s tragic tale of the doomed love between Rodolfo and Mimì which will end with Mimì’s death from consumption?

I realized in Act Two, which is set in the Café Momus, that in fact the audience was in the action, sitting in a café with Mimì, Rodolfo, Musetta and the boys. In some ways, this was an effective way to present “La bohème.”

Immersion in the Action

It pays to be close because what is noticed is the “play” aspect of the opera and the detailed characterization. The interplay between the four artist flat-mates becomes more particular. Audiences can appreciate the humorous nature of Schaunard, played in this instance by the brilliantly comic E Scott Levin (Ko-Ko in POP’s “Mikado”) and the earnest gravity of Colline played by Adam Cioffari, whose Overcoat Aria was a standout moment of dignity in the production.

What also came across in this production, enhanced by Kenneth Stavert’s magisterial baritone, was the overriding and reassuring authority of Marcello, the painter in the bohemian or hipster group and a true mentor for Orson Van Gay II’s Rodolfo, the poetic tenor whose heart will be broken by Mimì’s death.

Josh Shaw’s production brings out a fun aspect of “La bohème.” Quite often, in other productions, the antics of the four fellow-renters can be remote and unconvincing. Here their horsing-around seemed a natural consequence of flatting together and the production’s ethos of “rough theater.” There were plenty of laughs, quite often provided by Shaw’s supertitles, as when Rodolfo says his “worthless piece of shit heater” works about as well as Congress, but that maybe it felt like the humor carried on a bit too late into the show.

Ultimately, one might surmise that every production has its lump-in-the-throat moment. In this case, it was in Act Three when Marcello turned around to Mimì (Janet Szepei Todd) and said (per the surtitles): “That cough sounds bad.” One yearned for some greater sense of mortality from that point on and fewer laughs, maybe an end to topical jibes though it is essential to note that there was a major shock factor with regards to Mimì’s pallor when she entered in Act Four. The audience also fell silent at the tragic reprise of Mimì’s signature aria, “Mi chiamano Mimì”. And it must be further acknowledged that this is a production designed to attract audiences who do not insist on opera’s traditional song of love and (female) death.

Homing in on Softer Moments

The smaller setting was conducive to “close-ups.” While Orson Van Gay II’s top notes were thrilling, his quieter moments were more impressive. “I write love songs but mostly in my imagination” he sang, introducing himself to Mimì in Act One in a hushed way that was very touching.

The variety in Janet Szepei Todd’s Mimì was constantly engaging. Her big aria, “Sì, mi chiamano Mimì: (yes, this informal production still retains the singing in Italian) was simple and affecting and her reactions in Act Three on overhearing Rodolfo’s rationale for breaking up with her testify to genuine emotional responsiveness.

Another payoff through hearing a familiar opera like this in a smaller space is being closer to the dynamics between characters. It is always wonderful to home in on Mimì’s perceptive comments as Musetta (the rich-voiced mezzo Maria Dominique Lopez) goaded Marcello with her “Waltz Song.”

It was initially disappointing, especially at the beginning, to hear the opera’s lavish score on a piano. On the other hand, you could also argue that there was a dramatic gain in stripping away Puccini’s gorgeous orchestration. There was a truer sense of the stark tragedy of this tale of bohemian life.

Besides, the piano became an effective dramatic device in Act two when it appeared onstage in the café, and then became increasingly emotional due to the sensitive playing of Music Director Parisa Zaeri at the ends of Acts Three and Four, almost as if, having been onstage in Act Two, she was in there with the friends now.

One factor that wasn’t missed, surprisingly, was the chorus. Somehow the drama of this production obviated any need to hear massed ensemble, although Luvi Avendano as Parpignol effectively covered some of the Chorus’s lines.

All in all, this was an effective alternative to normal stagings of Puccini’s iconic work and there are refreshing benefits from such exercises.