Pacific Opera Project 2018-19 Review: The Magic Flute

Mozart’s Masterwork Gets the Ultimate Super Smash Bros. Treatment

By Gordon WilliamsWhen I interviewed Josh Shaw, Founding Artistic Director of Pacific Opera Project, back in December, I observed that Los Angeles’s Pacific Opera Theater or POP for short, is kind of “guerilla theater.” By that I didn’t mean that POP is experimental in its choice of repertoire but that it takes opera anywhere and – theoretically – everywhere by any means.

POP can mean “pop up” or it can mean “popular.” At that time, I was referring to the forthcoming “La Bohème”, to be done in a club-cum-wine bar in Highland Park, inspired by the company-personnel’s own somewhat bohemian lives, where operatic income has to be supplemented by extra waiting jobs or teaching assignments.

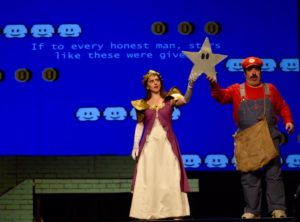

When Josh told me that POP’s first production for 2019 would be a version he would direct of “The Magic Flute” inspired by characters from 1990s video games like the Super Mario Brothers or Zelda – and when I realized that it was taking place in the 360-seat Debbie Reynolds Mainstage of North Hollywood’s El Portal Theater – I knew that this production would fit the “popular” side of their brief. And the timing seemed perfect, especially given the recent release of “Super Smash Bros. Ultimate,” the ultimate Nintendo video game mash-up.

But I wondered how it would work. Would lovers of opera be satisfied? How well might lovers of video games feel catered-for? Would the concept distract from the opera itself, the gaming reference obfuscate the music?

These approaches can be gimmicks which peter out in effectiveness after a couple of scenes.

Musical Embrace

I needn’t have worried.

POP’s “Magic Flute” is one of the freshest takes on Mozart’s 1791 classic I have come across. And I say this as someone who thought they would never again see a version of “The Magic Flute” as entertaining as Barrie Kosky’s German Silent-Film version.

Whether gamesters enjoyed the whole show I can’t say. I know that I began to take this “Magic Flute” more and more seriously as an operatic performance the more we delved into the evening. And without ever feeling less than intelligently entertained.

But I sensed that this was going to be a seriously insightful production from the opening moments of the overture played by conductor Edward Benyas’s well-prepared 22-piece orchestra. You might think that the overlay of 1990s video games would distract from the classic work itself.

I found myself developing a renewed appreciation of the music and of the story. I noticed that particularly with the first set of ensembles, noting down in the dark how well-balanced and meaningful was the quintet with Tamino (Arnold Livingston Geis), Papageno (E. Scott Levin), and the Three Ladies (Tara Wheeker, Ariel Pisturino, and Megan Potter) soon after Tamino has been given his assignment to rescue the Queen of the Night’s daughter, Pamina.

I must also mention the beautiful blend of the trio of Spirits later in the show (Emily Rosenberg, Amanda Benjamin and Christine Marie Li) who reminded me of Shakespearian beings in their agency and amused observation of the proceedings.

Nintendo Replaces Masonry

Partly, I suspect, the narrative clarity of this production was due to downplaying of the Masonic symbolism that supposedly underlies Mozart’s opera. The priest Sarastro (Andrew Potter) and the Queen of the Night (Michelle Drever) engaged in the show’s proceedings rather than presiding over the meaning as representatives of enlightenment and ignorance. Sarastro was a Kong, or king monkey, who collects bananas as rewards in game conventions, but Andrew Potter projected simple dignity in his two numbers. Michelle Drever’s coloratura runs were wonderfully clear and impressive but I think I might, on balance, have preferred to be looking up to her, elevated and stationary somewhere above the stage. How that would fit in with the production’s observation of video game conventions I don’t know.

Even in a show as persistently humorous as this there were moments of genuine musical poignancy. Arnold Livingston Geis, as Tamino (here Link from “The Legend of Zelda”), projected a beautifully clear and heroic tone in his aria, “This image of a princess fair, with long and flowing golden hair” (the equivalent to Mozart’s “Dies Bildnis”) and Alexandra Schoeny as Pamina (Princess Zelda, of course) conveyed genuine grief in her Second Act solo, known in German as “Ach, ich fühl’s…” There is plenty of dialogue in this work, but the rich timbre of her singing voice added a real maturity and depth to the role.

You would have to commend POP on a production where the video-game joke never wore thin, but one disadvantage was not being able to hear completely Eve Bañuelos’s first flute solo against the laughter; Tamino was playing an Ocarina instead of a flute, which no doubt was the reason for the enthusiasm. She shone later, though, during the music accompanying Tamino’s trials when laughter was inappropriate. In fact, all the woodwind work was excellent.

Entering Nintendo World

The libretto by Josh Shaw and E. Scott Levin was one of this production’s principal delights, beautifully working in references to games and their situations. The dragon that pursues Tamino at the very opening became Bowser from Super Mario Bros, the lava level that Mario often encounters becoming Link’s big obstacle. Tamino expressed his initial dilemma as being “down to one heart, can I just restart,” an overt reference to the “Legend of Zelda” franchise. And yet, I always got the impression that the words were being shaped to the music; that every line, no matter how laden with game references, had been sung to the score to make sure it would fit and convey the appropriate emotion and arc. Often, in fact, I didn’t mind that the words were substantially changed from Schikaneder’s original. Sarastro’s reference to the Egyptian gods, “O Isis und Osiris” became “Forget these fears, I know deep inside you,/ you have the strength, this quest requires./ Let wisdom, power, and courage guide you./ Lead you to find what your heart desires…” Those words beautifully underlined the music in simple, heartfelt thoughts. I wonder if the librettists were even consciously forestalling potential criticism of any tapering-off of game references with Papageno’s line: “A new level, looks the same! There are so few graphics in this game!”

E. Scott Levin, Shaw’s co-librettist, doubled as Papageno (here as Super Mario himself), emulating the dual role taken by the work’s original librettist, Emanuel Schikaneder, and, more importantly, producing a nicely-judged level of comedy. And of course we were happy for him when he found his Papagena (Laura Broscow, who of course was Princess Peach).

The production looked terrific. I liked that surtitles were part of the typography of a video game. I suppose in some ways this was what theater practitioners might call “rough theater.” There was a robust attitude to the “text” in interpolating other Mozart, such as the Divertimento K.136, during scene changes (read: “restarts”), but I couldn’t help feeling, as I looked around the Debbie Reynolds Mainstage with its 300-odd spectators that the original 1791 production at Schikaneder’s Theater auf der Wieden might have been more like this than the grander versions of “The Magic Flute” we get today in bigger houses.