Opernhaus Zürich 2023-24 Review: L’Orfeo

By Laura Servidei(Photo: Monika Rittershouse)

Opernhaus Zürich presents a new production of Claudio Monteverdi’s “L’Orfeo.” Premiered in 1607, “L’Orfeo” is not the first opera ever composed, but it is hailed as the first great opera. It stands out as the first to use music as a dramatic tool, employing diverse musical colors to express various emotional states. Its monumental success paved the way for the future of opera in musical history.

“L’Orfeo” is also the oldest opera still regularly performed in mainstream theaters, particularly after the original instruments movement of last century. Nikolaus Harnoncourt, a pioneer of this movement, had a significant connection with Zurich, where he staged a cycle of Monteverdi operas in historically informed performances during the late 1970s. These performances set a new standard and became a benchmark for all subsequent productions.

A Timeless Saga in Modern Times

The story of Orfeo is a timeless saga. Orfeo, a legendary musician in Greek mythology, fell deeply in love with Eurydice. Their happiness was short-lived as Eurydice died from a snake bite at their wedding. Overwhelmed by grief, Orfeo journeyed to the underworld to reclaim her. His music was so enchanting that Hades, the god of the underworld, allowed Eurydice to return to the living on one condition: Orfeo must not look back at her until they reached the surface. As they neared the exit, Orfeo, anxious and desperate, glanced back, causing Eurydice to vanish forever. Heartbroken, Orfeo wandered aimlessly, his music filled with sorrow.

In the mythological finale, Orfeo is either torn apart by maenads or succumbs to his grief. However, Monteverdi opted for an ending more aligned with the sensibilities of his time. In his version, the god Apollo, Orfeo’s father, descends to Earth and takes Orfeo to the heavens, where he can eternally gaze upon the beauty of Eurydice’s eyes in the stars.

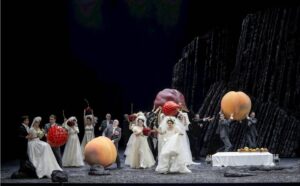

Director Evgeny Titov has chosen to set the story in a modern context, focusing on themes of death and how humans confront and cope with it. The sets, designed by Chloe Lamford and Naomi Dabaczi, create a somber atmosphere with a black, desolate landscape featuring large black rocks. From the very beginning, Eurydice’s white coffin is prominently displayed; she lies in it as if in a bed, while Orfeo digs the tunnel that will eventually lead him to the underworld. Death looms large even during the wedding preparations. The shepherds and nymphs are depicted in contemporary attire, with the men in tuxedos and the women in wedding dresses (costumes by Annemarie Woods), accented with quirky, humorous details such as oversized flowers in the men’s lapels.

The underworld is portrayed as a sterile, cold environment, characterized by steel and cold neon lights. Plutone and Proserpina are dressed in shiny silver attire, contrasting with Apollo, who wears a sparkling suit of red and gold as he attempts to persuade his son to ascend to Heaven with him. However, Titov chooses a different ending: Apollo leaves alone, and Orfeo shoots himself at the grave of his beloved wife.

The concept is clear, though some details seemed out of place, such as the gigantic fruits brought by the guests to Eurydice at the wedding, which did not add much to the story. Despite this, these elements did not detract from the overall enjoyment of the music—except for one instance.

Great Musical Performance

The orchestra La Scintilla, in addition to strings, featured cornettos instead of trumpets and a continuo comprising cello, gamba, double bass, harp, organ, theorbo, and baroque guitar. Ottavio Dantone led the ensemble in an exciting rendition of the score, using Bernardo Ticci’s 2016 critical edition. The initial, world-famous “Toccata” was brilliant, with the cornettos softening the brass of the baroque trombones to create a rich, spectacular sound. Dantone consistently paid close attention to the singers, ensuring his characteristic exuberance did not disrupt the beautiful balance between the orchestra and the stage.

The role of Orfeo doesn’t fit neatly into the later-developed fach system, and has been performed admirably by both tenors and baritones. Krystian Adam‘s powerful tenor, with its strong, well-projected lower register, was ideal for the role. His voice possessed a deep baritonal quality while remaining easy and natural in the high notes. His perfect Italian pronunciation was particularly crucial for Monteverdi’s work. Adam demonstrated a strong command of the style, utilizing every nuance for dramatic effect, both in the joy of marrying his beloved and in the grief of her death.

Although his portrayal of Orfeo sometimes lacked poise and tended towards over-enthusiasm, this might have been a directorial choice. Titov’s interpretation emphasizes Orfeo’s humanity; Orfeo, a demi-god, refuses to accept his wife’s death, defying the gods and the universe with his supernatural musical ability to return her to life, but ultimately fails due to his human doubts and fears. Titov’s focus on Orfeo’s human nature may have led to a more excited rather than calm and collected performance. Adam’s joy in “Vi ricorda, o boschi ombrosi” was infectious, with varied interpretation and ornamentation throughout the stanzas. In “Possente spirto,” his plea to Caronte to descend into hell, Adam showcased a beautiful array of ornamentation, using all his skills to persuade the formidable guardian of the underworld. The orchestral accompaniment, featuring two violins in the first stanza and two cornettos in the second, was delightful. Unfortunately, the accomplished bass Mirco Palazzi, interpreting Caronte, had his voice amplified and coming out of loudspeakers – a regrettable decision.

Palazzi had the opportunity to fully showcase his vocal prowess as Plutone, the king of the underworld. His bass was smooth and elegant, and his dialogue with his wife Proserpina, portrayed by soprano Simone McIntosh, was tender and sensual, with both singers conveying the love of this regal couple even in the depths of hell. McIntosh also played La Speranza, or Hope, the goddess who helps Orfeo reach the gates of hell. Her high soprano was more effective as Proserpina, where the higher tessitura suited her voice, and she vividly brought the character to life, particularly in the scenes where she seduces her husband into granting Orfeo’s wish. In contrast, in the role of La Speranza, she occasionally seemed to lose support in the lower register.

Eurydice’s role is brief, as she dies near the beginning of the opera, but Miriam Kutrowatz made the most of it with her silvery soprano and graceful stage presence. Jose Maria Lo Monaco played the crucial role of La Messaggiera, Eurydice’s friend who delivers the tragic news of her death to Orfeo and the chorus of nymphs and shepherds, detailing the entire scene. Lo Monaco gave a commendable performance as the sorrowful young girl, her mezzo-soprano voice bronzed and beautiful with a solid sense of style, though perhaps a bit lacking in projection.

Mark Milhofer was a very successful Apollo, his lighter tenor providing a pleasing contrast to Adam’s voice in their duet. Several other singers had small solo parts as shepherds, nymphs, or infernal spirits. At the end of Act two, the shepherds lament Eurydice’s death; the quartet of male singers—Massimo Altieri, Luca Cervoni, Tobias Knaus, and Yves Brühwiler—performed “Chi ne consola, ahi lassi” beautifully, almost like a madrigal. The chorus, from the Zürcher Sing-Akademie and prepared by Marco Amherd, was precise and moving in their lamentations, consistently attuned to the style. Their acting performance was also remarkable.