Teatro dell’Opera di Roma 2021-22 Review: Julius Caesar

Battistelli’s New Opera Shows Its Worth Despite Carsen’s Below Par Staging

By Alan Neilson(Photo: Fabrizio Sansoni)

In 2005, Vlaamse Opera premiered the first part of the Giorgio Battistelli’s Shakespeare trilogy, “Richard III,” to widespread acclaim. It has since gone on to receive a number of productions across Europe, although it had to wait until 2018 to receive its Italian premiere at Venice’s La Fenice. OperaWire was present for the occasion, and for what was an excellent production, commenting “Richard III is a dark, compelling and tightly constructed work, underpinned by a score that seamlessly connects and elevates the onstage drama, with a wonderfully fashioned depiction of Richard III himself, who dominates the work.”

Battistelli has now completed “Julius Caesar,” the second part of the trilogy. On this occasion, however, the Italian public has not had to wait 13 years to see a performance, as it was chosen to open Opera Roma’s 2021-22 season, becoming the first world premiere to open the company’s season since Mascagni’s “La Maschera” in 1901.

The production also marks Daniele Gatti’s final production as music director of Opera Roma.

Accessibility Across the Board

The libretto was written in English by Ian Burton, who condensed and modernized Shakespeare’s text but without deviating too far from the original storyline. Caesar’s assassination still forms the pivotal moment of the drama, and the great scenes, such as Anthony’s funeral oration, are all included. Where the libretto does diverge from the original is in its treatment of Caesar’s ghost, which involves itself directly in wreaking vengeance on his assassins, and appears throughout the final Act, pushing them into taking their own lives. It proved to be a dramatically sound decision that worked well in maintaining the dramatic momentum, and magnified Caesar’s powerful reputation as a man of action, even to the point of continuing his fight after death. Moreover, it also ensured that the character of Julius Caesar remains central to the opera from the beginning until the end.

Battistelli created a score that was complex, yet easily accessible, employing an orchestra with an enlarged percussion section that spilled into the boxes on either side of the auditorium. He successfully used this to create the atmosphere for each scene, which, for the most part, was of an unsettled or menacing nature. Either by design or error on the composer’s part, it was less effective in supporting and promoting the detail of drama.

Often the music would rumble along, almost in the background, before suddenly exploding loudly, with the brass taking a prominent role. Rhythms were employed to unsettle and to create a sense of foreboding, which was most dramatically displayed in the opening of Act one, scene five, where heavy, pounding rhythms alerted the audience to Caesar’s forthcoming assassination. It was also a very intricate composition, even in passages where the orchestra appeared to be taking a backseat. Battistelli’s handling of the detail was fascinating and his textural nuances wonderfully woven.

Daniele Gatti produced an intense and detailed performance from the Orchestra del Teatro dell’Opera di Roma, which proved to be a hugely enjoyable and interesting experience for the listener.

Carsen’s Below Par Direction

Robert Carsen, who was responsible for the excellent staging of “Richard III,” was again encharged to direct “Julius Caesar.” Such is the quality of Carsen’s productions that expectations always run very high, and in this case, it worked against him. Although this was an acceptable staging in which the characters were clearly defined and the drama clearly focused, it never reached the heights of “Richard III,” nor of such recent production as Janáček’s “Osud” in Brno, or Monteverdi’s “Il Ritorno d’Ulisse in Patria” in Florence. Normally, Carsen is able to inject that extra something into a production that challenges the audience and sparks the imagination, but not on this occasion. There was also a tendency for Carsen to rely on obvious theatrical devices and unimaginative stage designs. If it were another director’s name attached to this production, then it is likely the impression would have been less disappointing.

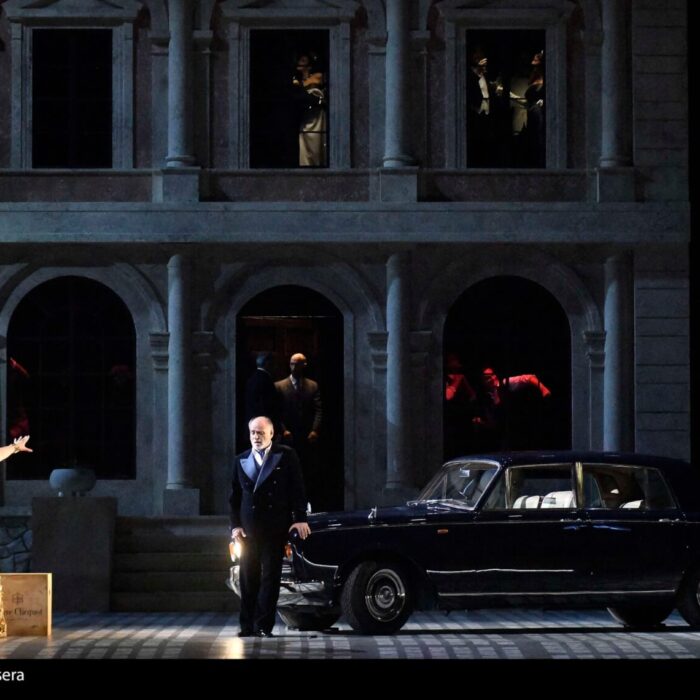

Be that as it may, the idea behind the staging was well-conceived. Carsen moved the setting to present-day Italy, successfully reflecting the fact that apart from openly assassinating people on the floor of the Senate, the art of politics has not really changed. It is still an arena in which ambitious personalities, full of hubris, vie with each other for power, in which they manipulate, cajole, threaten and destroy each other while paying only lip service to the concerns of the population. Of course, that honest politicians do exist, and that many others operate under a variety of delusions, adds a veneer of respectability and opens up the space for the political theatre to be acted out.

The sets, designed by Radu Boruzescu, varied between the fairly mundane to the impressive, in which the scene in the Senate was the most effective, with its raked tiers of red seats and desks providing an excellent backdrop for Caesar’s murder. Likewise, the wooden scaffolding which dominated the final scenes, in which a grey mist swirled across the stage, created a perfect post-battle atmosphere for Caesar’s ghost to pursue his assassins.

The costume designer Luis F. Carvalho had the senators dressed in dark suits, typical of the bureaucrats, administrators, and managers who populate today’s centers of power, whilst the populace were attired in the usual casual clothes of the 21st century, jeans, trainer and t-shirts, which successfully created a gap between the powerless, who can do little more than protest, and the powerful who compete between themselves for the top positions. On the negative side, however, the pervasive dark visual colors of the costumes reinforced the dark vocal textures of the score, and although this can often be found in the staging of tragedies, the lack of contrast at times dulled the presentation.

A Strong Singing & Acting Cast

The cast is fairly large, with a number of extensive solo roles for the male voice. Apart from members of the chorus, the work has only a single female role, that of Caesar’s wife Calpurnia, reflecting the political world of Ancient Rome and, to a lesser extent, that of present-day Italy. It is also a work that was heavily weighted towards darker textures. Declamatory singing was employed almost exclusively throughout, as the text shifted between exchanges and reflective monologues, which never fully bloomed into what could be termed an aria, notwithstanding Octavius’ short contribution in the final scene. It was, therefore, essential that the singers produced strong acting-singing performances with their attention focused on their characterization and the dramatic context of the drama if the opera was to come alive.

They did not disappoint, with even the minor roles being strongly performed.

Bass Clive Bayley produced an excellent performance in the role of Julius Caesar, in which he captured his vanity, courage, and heroic demeanor. His singing was detailed, clearly articulated, and expressive. And despite a little weakness in the upper register, the voice exhibited a rich, pleasing tone. His transition from a living breathing Caesar to a ghost was expertly achieved; significantly different from each other, but retaining the same underlying character.

Baritone Elliot Madore successfully brought out the conflict at the heart of Brutus’ character, in which his love for Rome triumphed over his love for Caesar. Although he occasionally struggled to be heard during the louder passages of the music, he produced a strong singing-acting performance in which his character’s dignity and courage were clearly evident.

The role of Antony provided baritone Dominic Sedgwick with many opportunities to showcase his interpretative abilities. He not only brings Act one to a close with the soliloquy “O pardon me, thou bleeding piece of earth” but also had one of Shakespeare’s most famous monologues “Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears!” to perform. His accomplished presentation of both pieces, along with his overall interpretation, was finely crafted, in which his attractive timbre, intelligently crafted phrasing, vocal clarity, and versatility impressed.

Contralto Ruxandra Donose in the part of Calpurnia displayed an impressive degree of vocal agility with her well-crafted and emotionally intense phrasing, as she pushed her voice upwards towards its limits, skillfully highlighting her anxiety which, at times, bordered on hysteria.

The manipulative Cassius was essayed by tenor Julian Hubbard, who gave an energetic, precise, and vocally expressive portrayal in which he displayed agility and a strong, attractive upper register.

Tenor Michael J. Scott in the role of Casca, who doubts Caesar’s motives, believing him to have eyes on the crown, convincingly made his case with a passionate and strong argument, displaying skill in accenting the vocal line, while imbuing his voice with conviction.

The tenor Hugo Hymas as Brutus’ servant Lucius produced a neatly essayed performance in which he showed off his attractive voice in a lyrical presentation.

In the relatively small part of Octavius, Alexander Sprague made a strong impression. He possesses an appealing tenor, which he used with authority to voice his ambitions and establish his ruthless character in the opera’s final words.

All the minor parts were successfully interpreted, with tenors Christopher Lemmings and Christopher Gillett, and baritones Allen Boxer and Alessio Verna cast in nine minor roles between them. However, it was bass Scott Wilde who managed to catch the attention with his clear articulation and warm timbre in the roles of Decius and III Plebo.

The chorus was used to good effect and was particularly successful in highlighting the ease with which the populace can be manipulated by politicians. Under the direction of the Chorusmaster Roberto Gabbiani, the Coro del Teatro dell’Opera di Roma, singing in English and Latin, added some welcome color to the predominantly dark voices of the soloists, as well as intensifying the drama at crucial points. At other times, it was used to enhance the mood, as in the opening scene in which its offstage murmuring created an ominous, unsettling atmosphere. Its singing was of high quality, throughout.

Overall, “Julius Caesar” proved to be a dramatically and musically interesting work. However, it was not to the same standard as Battistelli’s “Richard III.” Carsen’s fairly mundane staging combined with a cast overwhelmingly dominated by male voices created a homogeneity of visual and vocal coloring which worked against exploiting the work’s inherent contrasts and dampened the opera’s overall dramatic impact. It was not, however, a fatal flaw by any means, and the opera has much to recommend it, and with a more imaginative staging it may prove to be the equal of “Richard III.”

The third part of the trilogy will be Shakespeare’s comedy “Pericles.”