Opéra National de Paris 2019-20 Review: La Traviata

Pretty Yende & Benjamin Bernheim Shine In Simon Stone’s Revelatory Production

By Mauricio Villa(Credit: Charles DuPrat / Opera de Paris)

“La Traviata” by Giuseppe Verdi is probably one of the most popular operas from this composer and from the opera catalogue in general. Based on the the play “La Dame aux Camelies,” which has been adapted from the novel with the same tittle by Alexandre Dumas (son), was inspired on the life of Alphonsine Plessis, a courtesan with had an affair with Alexandre Dumas’s son. In sum, it is a pure French story that the Paris Opera staged at Palais Garnier, with a new production by Simon Stone and the thrilling debut of Pretty Yende as Violetta.

Obviously, in this context, the expectations were very high and the result was a tremendous success.

A Story For Our Times

A new production of La Traviata, opening the season and directed by a modern director is quite a challenge, especially when the new production is conceptual and modern. First of all, what Stone did was stage the opera in modern times; this implies the use of mobile phones and modern costumes. But if we look back to Verdi’s premiere one of the problems he had was setting the opera on the same period he lived in, as this was something never done before. People were used to seeing Kings, gods or legends from the past and did not want the see themselves reflected on the stage. In fact, Verdi had to change the staging to the middle of 1700 to pass the censors. So basically, Stone did what Verdi wanted with the highest of quality. All the scenes are wonderfully directed, nothing is left out, the relationships between the characters are believable and moving and the staging is magical.

The set, by Bob Cousins, is basically a cube placed on a revolving platform (yes, it seems that every director nowadays uses a revolving stage) which made the transitions between scenes and acts very smooth and quick. For example, no curtain came down for the transition between scene one and two on the second act. In old theatre, they would use a revolving stage to show different parts of the sets only turning between scenes; but today modern directors ( as I commented and my past reviews of Laurent Pelly’s “I Puritani” or Damiano Michieletto’s “Luisa Miller”) integrate the movement into the action, turning several times, and in this case always changing something.

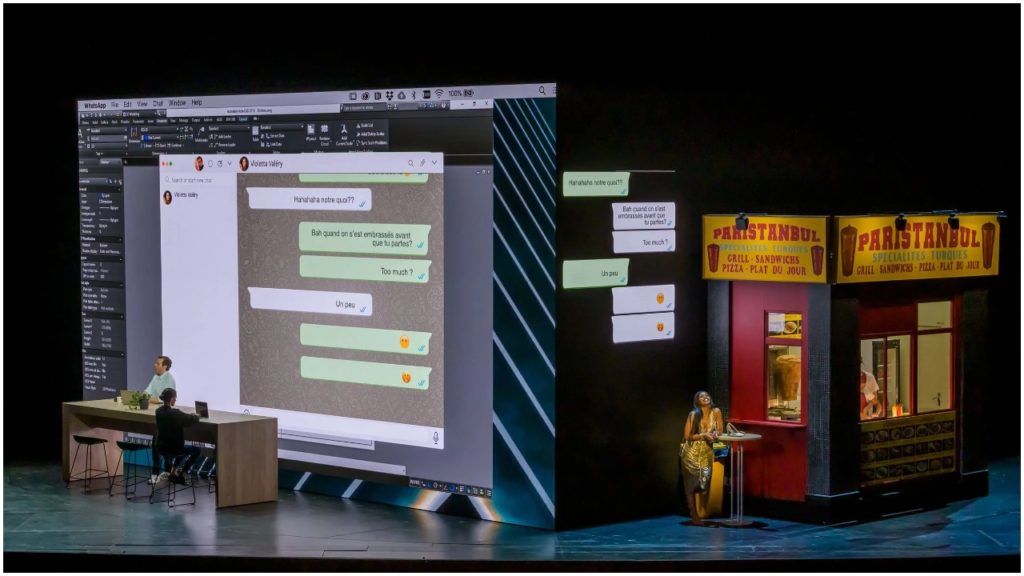

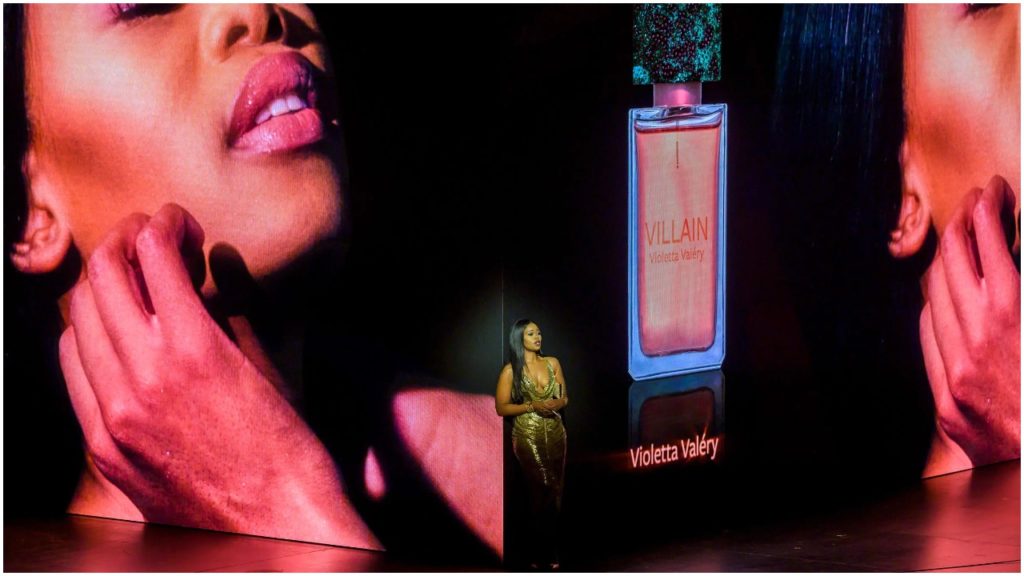

When you enter the theatre, the curtain is up, and you see two sides of the box, as the cube is in a diagonal position, which shows Violetta’s closed eyes. When the overture begins with the sad theme of “sickness” played by the strings, Violetta’s eyes open with the image turning into a perfume advertisement where Violetta is the model. The box starts turning very slowly as the “love theme” begins and we see projections of Instagram, Facebook and Whatsapp presenting Violetta as a media influencer. We see lots of conversations, pictures, partying…The box stops with a corner facing the audience again (they always stopped the box on a diagonal) as the first act begins and we see the entrance to a famous club where the guests are queuing. We see how Violetta, dressed in a sexy night dress, skips the queue as a VIP guest.

The box turns to reveal how two walls are gone and show a giant pyramid of crystal glass and an immaculate white inside walls. Alfredo climbs up the pyramid at the beginning of the brindisi, opens a champagne bottle and pours the champagne. When Violetta feels sick all of a sudden and she leaves the guests at the party, the stage turns and we see the back of the club with trash bins and boxes, Violetta lights a cigarette as Alfredo enters for the love duet. We go back to the party for the farewell chorus and leave Violetta alone for her aria. As the cabaletta begins it turns again, stopping to form a street corner with Kebab kiosk, and a café on the other side where Alfredo is using his computer to send messages to Violetta during the supposed off-stage: “Amor e palpito.”

This goes on throughout the performance, showing different projections when the walls face the audience and different ambiences when the square is open. We have Alfredo crushing vines during “De miei bollenti spiriti,” a real cow that Violetta is milking when Alfredo’s father appears at their country side house. We see a park with picnic tables, another club for Flora’s party, a square with a statue, and a hospital first with several patients receiving treatment and then just a single hospital bed lost in the huge white space for Violetta’s death scene. When she gets out of bed in “Strano…cessarano gli spasmi,” we see Violetta walking into a deep fog inside the cube as the box finally closes. The ending is really hair-raising.

It is a fascinating and imaginative production, though one might understand the negative reaction of an audience who might expect something more tradition and might be shocked by the explicit sexual references during Flora’s party. The only negative point would be the contradictions that sometimes happen between the libretto and the actions. For example: Violetta is writing a message on her mobile but Alfredo demands the paper she is supposed to be writing in “Dammi quel foglio.” This happens quite often during the opera.

I consider that directors should find solutions to these matters rather than rely on the audience’s ignorance of the language being sung or suspension of disbelief in favor of their concept. This is a case where it might be worth adjusting the libretto. This might anger the purists, but the reality is that if you are adapting a work originally written with a specific time period in mind to another, then what could possibly be wrong with making slight alterations to text to suit a concept that already goes against the original intentions?

(Credit: Charles Duprat / Opera de Paris)

First Time Traviata

Pretty Yende sang the iconic role of Violetta Valery for the very first time.

It must take a lot of courage to debut such a demanding role on the stage of Palais Garnier rather than in some small unknown theater (something that singers used to do while debuting big roles). But if there is something that marks Yende’s character is her determination and fight. On this occasion, she achieved a great success and showcased great quality as both singer and actress of a Violetta who was selfish, strong, arrogant, caring, vulnerable, resigned, sick. We saw the development of the strong social influencer into a simple woman in love who sacrifices her happiness for Alfredo’s sake before eventually becoming a strong but sick woman who has been abandoned by the society that once adored her.

It has always been said that Violetta is a role that requires three different kinds of soprano: a leggera for the first act, a lyrical for the second and dramatic for the third. Yende is a pure Lyrical soprano with a strong center and low register that are well-projected. She also has solid coloratura, no doubt the result of her bel canto experience. It has been through hard work that she has managed to obtain her upper register, and she can sustain a high F easily as she proved during the performances of “Lucia di Lamermoor.” But her high notes often seem manufactured and completely change the timbre of her voice.

But it was clear that Yende’s voice was going to handle the role quite well when she sang her first phrase“Flora, amici, la note che resta.” Most light voices suffer here and are unheard over the orchestra, but this was not the case with the South African soprano’s singing, as her beautiful, velvet timbre and the low C projected amply. The roulades in the duet with Alfredo seemed easy and precise, like she was laughing at him.

Yende began the recitative: “E strano, e strano!” paying attention to every word, every feeling behind the music, shading every phrase with different colors. Her interpretation of “Ah forse lui” was extremely moving and she employed sweet mezza voce and pianissimi singing. In “Follie, folllie…sempre libera” she displayed ample vocal pyrotechnics and strong emotions with her high C in “ritrovi” potent and strong. After Alfredo sings “Amor e palpito,” the cadenza’s coloraturas were so fast that Joan Sutherland came to mind; as no one else has performed these crazy scales with such speed and grace. As expected, she finished the cabaletta with an astonishing high E flat.

In the second act, she sang “Ah no! giammai! No, mai! with dramatic force and volume before transforming her voice into a lamenting pianissimo with “non sapete quale affeto.” Her low B flat that ends the line “l’uomo implacabile per lei sara!” was solidly positioned and audible. “Dite alla giovine” was sung with tenderness, as she used her ethereal mezza voce.

After the duet with Germont she reaffirmed her authority over the role. The tessitura of the second act, despite several ascensions to high B flats, is centrally positioned and it is in the middle of the voice where Pretty Yende shines. She did it all with great beauty and poise: she sang forte, with mezza voce, with slender pianissimi, and with potent low notes. Her “Addio del passato” was really moving with beautiful pianissimi on the high A in contrast with a forte sound on “Ah! tutto, tutto fini.”

(Credit: Charles Duprat / Opera de Paris)

Tenor

Benjamin Berheim, the French young tenor who performed Alfredo, was a gratifying revelation. He has a splendid pure lyrical voice with a dark timbre and even a baritonal quality in the middle and lower register of the voice. His high notes are round and well-projected, but most impressive of all is the potency of his voice when he sings soft, whether in mezza voce or pianissimo.

His interpretation of the duet “Un di, felice” was remarkable for his use of the dynamics and mezza voce. The same could be said for his aria “De mie bollenti spiriti” that he had to sing while crushing vines, an action that is undeniably not easy to do when you have to sing long legato phrases ascending to high A flats.

He sang the cabaletta “Oh! Mio rimorso” with rage and fury, including with two well-sustained high B flats. He proved his acting qualities when he finds Violetta has dumped him and at Flora’s party in the second part of act two when Alfredo is completely drunk and wasted ( in this production). He sounded menacing during “Ogni suo aver tal femmina,” always keeping his torrential voice in control, but full of emotion. He threw the bills in Violetta’s face and during the next chorus he kept grabbing the bills from the floor and throwing them at her.

He was at the same level in the third act, singing softly in “Parigi o cara” or letting his whole voice out in “Oh mio sospiro, oh palpito.” If not for Yende’s potency as Violetta, he would have been the true star of the show.

Two More Masters

Ludovic Tézier, who played Giorgio Germont, was equally wondrous. If we compare Germont’s score with other Verdi baritone roles, the part is quite short and vocally less demanding. The role is written mostly on the middle register which is always a comfort zone for the singers; the baritone does not have to go higher than G flat. As usual, however, he has to sing long legato phrases, some of them ascending to high F while keeping the fluidity of the melody. Tézier was more than up to the challenge.

It is an intimate role and there are not furious outburst or heroic cabalettas and we only see his vulnerability during the last few phrases he sings at the end of act three when he regrets the harm he has done. Teczier’s voice is rather generous, so the first high F during his entrance in ”Si, dell’incauto” sounded thunderous. Then he gave off a sweeter timbre for “Pura si come un angelo,” interpolating an extra high G flat in “E dio che ispira, o giovine.” His interpretation of his aria “Di provenza” was sublime, with the baritone attacking the final high G flat with clean sound.The high F of “no, non udrai rimproveri” that closes this scene in “Ah Ferma” was heard clearly over the forte orchestra.

Michele Mariotti was in charge of the Orchestra de L’Opéra National de Paris. This young conductor is usually associated with Bel canto and for his vitality and ability to extract all the passion from the music in those score. If he manages to make Donizetti sound like verismo you might already guess what he did with Verdi score. He exaggerated all the dynamics to the maximum potential so that certain sections of the score sounded new and fresh. For example, he began the last verse of the brindisi with the chorus and the principal singers singing piano and rallentando, but kept building up tension as the orchestra and singers began gaining speed, returning to the set tempo and doing a crescendo to a Forte finish. The effect was fantastic.

He sustained adagio tempi when the scenes required it, but he chose a quicker tempo in many sections of third act like “Oh dio morir si giovine” or “non morrai non dirmelo,” reinforcing the idea that of death’s inevitability. He also had the strings to play forte at the beginning of “prendi quest’è l’immagine,” creating a Requiem atmosphere, despite the whole orchestra being marked ppp in the score.

He presented a nearly complete version of the score only cutting one repetition of Germont’s cabaletta and a small fragment from Vthe ioletta-Alfredo duet in act three that is usually cut.

This performance of “La Traviata” is one that you will never forget. Featuring an excellent and modern approach that respects Verdi’s music and Piave’s libretto, and the best possible cast and conductor, it would have been wonderful to see this showcase recorded for future release online or physical media.