Opera Meets Film: The Transcendent Fusion of Yuki Mishima’s ‘Patriotism’ & Wagner’s ‘Tristan und Isolde’

By David Salazar“Opera Meets Film” is a feature dedicated to exploring the way that opera has been employed in cinema. We will select a film section or a film in its entirety and highlight the impact that utilizing the operatic form or sections from an opera can alter our perception of a film that we are viewing. This week’s installment features Yukio Mishima’s “Patriotism.”

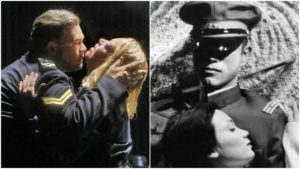

Yukio Mishima’s “Patriotism” is arguably one of the finest cinematic adaptations of Wagner’s “Tristan und Isolde.”

The 28-minute short silent film tells the story of Lieutenant Takeyama, a member of the palace, and his wife Reiko as they commit seppuku when Takeyama is ordered to kill his fellow mutineers. The film, set in the Noh theater, is underscored throughout by Leopold Stokowski’s Symphonic Synthesis of “Tristan und Isolde.”

After the opening title cards, we see Reiko in a domestic setting, the music from the first Act confrontation between Tristan und Isolde at the forefront. With the sustained brass notes, Mishima uses the double exposure effect to show us Reiko remember sensual moments with Takeyama. While on the surface Reiko’s seemingly relaxed disposition might seem like a fierce contrast with the tense meeting between Wagner’s titular heroes, the sexually charged imagery also emphasizes and reminds the viewer of the sexual tension that pervades this opening scene in Wagner’s music.

With the sexual themes of the film already established, the music shifts to the horn calls that kick off the second act. Here Reiko stands up out of her fantasies, finding Takeyama arriving. They sit together for a moment and vow to commit seppuku together. The music playing here (“O sink hernieder, Nacht der Liebe) has the corresponding text:

“Descend,

O Night of love,

grant oblivion

that I may live;

take me up

into your bosom,

release me from

the world!”

The climax of this passage is met by title cards explaining the two succumbing and revealing their deepest passions before showing us a wide shot of their naked bodies spread across the stage. Mishima continues the exploration of love and violence by cutting to Takeyama’s sheathed sword.

From there Mishima cuts to match cuts of the extreme closeups on the two characters’ eyes staring toward one another. These images emphasize the union of the two, almost shadowing the invocations of “Tristan you, I Isolde, no longer Tristan” and “You Isolde, Tristan I, no longer Isolde!” later in the duet. In this moment of highest sexual pleasure, the two are joined as one.

As the love music continues, we get more extreme closeups highlighting the act of sexual bliss, the music’s transcendent qualities given a visual equivalent.

We move onto the ensuing section of the film where Takeyama commits seppuku. This drawn-out moment is underscored first by Tristan’s Act three cries of “Isolde” and then “So starben wir, um ungetrennt / “Thus might we die, that together, ever one, without end,” the moment he plunges the knife into his abdomen.

What follows is a graphic and tortuous scene, Mishima juxtaposing the grisly images of Takeyama’s suicide with Reiko’s pure face. The cutting grows tighter and quicker as he nears his end before plunging a sword into his neck. Reiko’s jerky movements as she attempts to stand mirror Takeyama’s convulsions and the sequence climaxes with Brangäne’s sublime warning as blood splays all over a white wall.

From there the sequence transitions to Reiko’s suicide which will inevitably be underscored, eventually, by the climactic “Liebestod.” Mishima takes his time to build her suicide, almost playing and in some ways subverting the audience’s expectations of the music itself. She tenderly moves her dead husband’s body into position, caresses his face, and then plants a gentle kiss on his lips. Moments later, she unsheathes her knife and licks it, uniting concepts of love and death in a manner, that while foreign to Wagner in its explicit violence, nonetheless matches much of his thematic output. Reiko looks on at her dead husband one last time with the first semblance of a smile and following a jump cut from a medium shot to a closeup (the only such instance in the film), the knife drives toward Reiko as Isolde would sing her final F sharp on “höchste Lust!”

The film ends on a shot of the two lovers lying together in death.

Thematically, Mishima ensures a consistent link with Wagner’s story, down to the details leading up to the two hero’s deaths and the famed “wound.” Tristan suffers from a self-inflicted wound that will not leave him, eventually succumbing to it when Isolde returns to him. Had it not been for his betrayal of his uncle King Marke and his country, he never would have had to confront Melot and die. At the close of Act two, Tristan literally runs into Melot’s sword.

Meanwhile, Takeyama’s seppuku is necessary if he is to avoid betraying his comrades in arms who recently executed a failed coup d’état. His choice is to either follow the imperial order or kill himself in order to avoid betraying his fellow mutineers. Again, he is a man who betrays his nation and opts for upholding his values, similar to Tristan deciding to defend his love for Isolde against all odds.

One also cannot overlook the stylistic implications of eschewing of the “human” voice altogether in black and white silent film. Mishima created the picture in 1966, well past the era of the silent films when there would have been no impediment for him to create a sound and color picture. Other filmmakers during this era, including Masahiro Shinoda with “Double Suicide,” had created films in the Noh style similar to what Mishima was exploring. So Mishima’s deliberate choice becomes all the more prevalent when one looks at his soundtrack selection for this opera (also sans singing voices).

For it is here that we find the two artistic expressions fused in their purest means of expression to create a new whole.

In this iteration, the imagery, not the words, becomes the poetry that Wagner always sought in his music dramas. Conversely, Wagner’s music, not dialogue in any specific language, gives new life to Mishima’s short story as expressed through imagery. It is here that the ultimate artistic transcendence takes place. Like the lovers in Wagner’s music drama and Mishima’s story, the fusion of two disparate expressions and beings (cinema and opera; Tristan and Isolde; Takeyama and Reiko) form a sublime new whole.

Watch the film below:

Categories

Opera Meets Film