Opera Meets Film: How Wagner’s ‘Ride of the Valkyries’ Informs Character & Theme in Fellini’s Iconic ‘8 1/2’

By David Salazar“Opera Meets Film” is a feature dedicated to exploring the way that opera has been employed in cinema. We will select a film section or a film in its entirety and highlight the impact that utilizing the operatic form or sections from an opera can alter our perception of a film that we are viewing. This week’s installment features Fellini’s “8 1/2.”

Early on in Fellini’s seminal masterpiece “8 ½,” Guido Anselmi, heads over to a luxury spa that is brought onscreen to the sounds of Wagner’s iconic “Ride of the Walkyrie’s.”

The music actually bridges a previous scene in a bathroom, the famed trills providing the setup for the shift in scenery (worthy of note – the music starts up on a shot of Guido looking into a mirror and turning on a light). The first images we get are a series of closeups of older women staring right at the camera. Eventually, Fellini adds in older men, a live “orchestra (more like a couple of musicians somehow playing the epic piece), and a conversation between Guido and a critic.

What’s particularly notable from a filmmaking standpoint is how Fellini manages to not only cut to the prominent arrival points of Wagner’s music, but he also manages to time his various camera moves to it as well. We might see a dolly from one character arriving at a particular musical downbeat or a rack focus employed in a similar musical manner.

But what does it all mean? What does it matter? There’s a lot of implications, many of which are arguably hard to piece through given that Fellini’s film itself is full of abstraction and symbolism.

Visually, Fellini brings us into the scene from Guido’s point of view. This is expressed through the closeups of elderly characters looking into the camera, making direct contact with the viewer, who in this case is Guido. From the opening sequence in the traffic jam (a dream), Fellini has established that we will be witnessing the film’s world through the stream of consciousness of its character, so it stands to reason that this scene is an extension of that.

So how Guido views the world is undeniably colored by how he hears it as well. So the images of the people looking at him, colored by Wagner’s epic music not only create a sardonic vision of that world in this opening scene; seeing the elderly people at rest directly counterpoints the intense fury and sweep of Wagner’s iconic music. But it also highlights what we will come to realize about this “relaxed” and what it means to Guido – for, at this place and several others, Guido will be constantly bombarded by people walking up to him and trying to grab his attention.

In this very same scene, we will also get the overture to Rossini’s “Barber of Seville” following right after the “Ride of the Valkyries,” serving several functions. Not only does the Rossini overture, a comic one at that, further accentuate Guido’s general feeling toward his environment, but it serves as a stylistic complement/counterpoint to the Wagner, which fits beautifully into Fellini’s overall frenzied and dreamlike filmmaking in this sequence and the film at large.

To further this point, the Rossini overture suddenly freezes midway through the scene as Guido spots the angelic image of Claudia, the muse for his next film. Suddenly time stops, the music stops and all we get is quiet and peace, a major contrast to the torrid energy of both the Wagner and Rossini. This emphasizes the piece and sense of inspiration that Claudia inspires in Guido for the briefest of moments. And then suddenly, after a few shots of Claudia from a distance, the Rossini rushes back and the spa’s energetic life comes back.

This scene on its own is a masterful display of how music expresses the character, form, and energy of a scene. But that’s not the last of the Valkyries in this film. In fact, what we get next not only serves its own purposes but builds on this sequence.

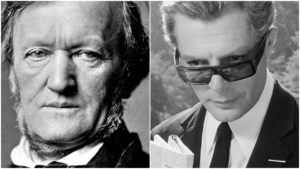

Guido as Wotan?

Much later in the film, we get a dream sequence of Guido in what seems to be a harem where he lives as the king and ruler of all the major women in his life: his wife, his lover, his first sexual fantasy, actresses in his films, etc. And what music accompanies the end of this segment? The “Ride of the Valkyries.” And this is literally a ride as Guido gets to live out a fantasy of dominating the women and being pampered by them, accompanied by some relaxed parlor music. But then when he tries to eject one for being too old, they rebel against him, with the words “It’s not fair” ushering in the famed Wagnerian passage.

In many ways, this scene isn’t too far from “Die Walküre’s” ALMOST corresponding confrontation between the Valkyries and Wotan. Brünnhilde rebels against Wotan when she aids Siegmund and runs away with Sieglinde. She seeks the help of her sisters and they protect her from their father Wotan, who lords over them and commands them in battle. They are his servants in addition to being his daughters. But when he sees them rebel, he threatens to take away their immortality, ultimately getting his way and having them turn over Brünnhilde.

What happens in the corresponding Fellini scene underscored by the Ride of the Valkyries? Guido, faced with the revolt of the women, literally whips them into shape and ultimately gets his way, escorting the aging actress out of his harem.

While I don’t think that Fellini had Guido as a Wotan stand-in on his mind in making the film (he was making this film as a means to work on his own insecurities and artistic problems), it’s impossible not to see the similarities between the filmmaker and the Wagnerian God. For Wotan wants to rewrite his own narrative. He needs to free himself of the curse of the Ring and his only way to do so is to have a hero without fear save him. So he literally creates a son, raises him to have no fear, and then sets him out in hopes of reviving his life. But then his entire plan goes to hell and he finds himself trying to right the wrongs, only making things worse.

Guido, as a film director, is in search of his next film, but he’s stuck at every turn and every action he takes only seems to worsen his situation. And like Wotan, he has a major problem with faithfulness with his relationship with his wife Luisa becoming a focal point not only of the dream, but the film’s second half; it goes without saying that Wotan’s wife Fricka becomes a major engine in “Die Walküre’s” storyline and the source of major tensions for Wotan.

Was this what Fellini intended? We won’t know now, but there is no doubt that Wagner’s epic opera was on his mind with regards to “8 ½,” especially considering that its most iconic music makes major appearances.

Categories

Opera Meets Film