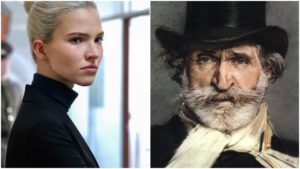

Opera Meets Film: How Verdi’s Music in ‘Anna’ Provides Nuanced Character & Thematic Development

By David Salazar“Opera Meets Film” is a feature dedicated to exploring the way that opera has been employed in cinema. We will select a section or a film in its entirety, highlighting the impact that utilizing the operatic form or sections from an opera can alter our perception of a film that we are viewing. This week’s installment features Luc Besson’s “Anna.”

In an earlier installment of Opera Meets Film, we talked about how Luc Besson’s style of filmmaking is encapsulated in his use of opera in “The Fifth Element.” With his most recent film “Anna,” opera is on the musical menu yet again.

As with “The Fifth Element,” Besson only brings operatic language into the film in one instance. In a soundtrack that runs a wide gamut, the inclusion of opera only adds to this sense of a musical buffet. On a superficial level, his inclusion of the opera is meant to serve an immediate narrative function of scene setting as the story shifts to Milan.

What’s the first thing a casual moviegoer might think of when they picture Italy? Opera will be one of those things. And what is the most iconic and popular opera tune for the general public? “La Donna è mobile.” What comes in at number two? Among a number of choices, the Brindisi from “La Traviata” will probably be there.

So on this surface level, the operatic choices are rather uninspired and border-line cliché in choice and execution. But Besson, for all his faults (and this film is riddled with them) is a sophisticated pop artist. He doesn’t select things at random. He knows that the opera pieces he has picked will definitely hit the audience on a visceral level and connect them instantly to his settings. But the choices aren’t coincidence as far as the work’s themes go.

“La Donna è mobile” is the most misogynistic opera aria ever written, describing women as fickle and thus interchangeable. “Anna” is nothing if not a filmmaker’s knowing exploration (and exploitation) of the male gaze. Her entire story starts with a man identifying her in a marketplace and deciding that he wants her to be a model in Paris. From there, we find out that Anna is caught in a whirlwind where her fate seems to be in everyone else’s hands but her own. In fact, she’s figuratively passed around from one place to another, from one agency to another, even from one man to another (and to a woman even). She is constantly forced to change her role to suit her needed purpose as an undercover KGB agent. She is an object for male sexual desire throughout and is framed as such. What is she doing when the “Rigoletto” aria kicks off? She is posing for an obnoxious male photographer.

At his point in the story (as we later find out), Anna is finally on her way toward her much-desired freedom from the KGB. And her first step toward that freedom is to ditch the modeling business. Flanked by two other models dressed similarly (while she is centered in the frame, the women are framed in such a way as to seem identical and thus interchangeable in the context, further supplementing the aria’s theme), she starts off tame an obedient, “La Donna è mobile” playing in the background. But halfway through the session, the music shifts to the Brindisi, suggesting a passing of time and it is here that Besson makes his mark, juxtaposing the aria’s celebratory feel with a more brutal visual appearance. It is during this section of the scene, during an operatic section that celebrates love and freedom, Anna loses her cool.

The photographer starts up a phone call after commanding the models to stay locked in their place, like machines. He rambles on, dismissing them. Anna, who has had enough, leaves her post and runs up to the photographer. She knocks him over and starts beating him as Verdi’s music ramps up. The brutality of the visuals counterpoints the music beautifully, but plays thematically and structurally.

On a structural level, it is a direct response to the start of the scene when theme and music were perfectly aligned, but the psychology of the character was completely out of synch. No one believes that Anna’s feelings are reflected in the bouncing theme sung by the Duke of Mantua.

But here, there is a reversal. While the visuals are not aligned with the music’s jovial feel, this is a release for Anna. This is the first major instance where we see her, chronologically, rebel against an institution that was chaining her. Verdi’s music actually reflects and reveals her inner psychology, giving the sequence a structure development and unity.

Thematically, this counterpoint between what is externally portrayed and internally felt is at the core of the entire film’s theme of deceit. The entire film constantly shifts back and forth in time, unmasking details of events we think we understood, only to flip them on their heads. Nothing is what it appears to be. The “Traviata” music is not meant to emphasize the violence onscreen, but the very feeling we can’t see but that lies hidden within. Counterpoint thus goes against the grain while also emphasizing the deeper psychological development within.

Categories

Opera Meets Film