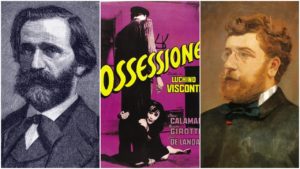

Opera Meets Film: How the Music of Bizet & Verdi Adds Irony to Luchino Visconti’s ‘Ossessione’

By David Castronuovo“Opera Meets Film” is a feature dedicated to exploring the way that opera has been employed in cinema. We will select a film section or a film in its entirety and highlight the impact that utilizing the operatic form or sections from an opera can alter our perception of a film that we are viewing. This week’s installment features Luchino Visconti’s “Ossessione.”

Opera Wire has previously explored Luchino Visconti’s use of opera as a narrative element in three color films from his middle and late-career. These recreate grandly the rich milieux of specific historical periods: “Senso” and “The Leopard” depict (respectively) the aristocratic worlds of the Veneto and the Sicily of the Risorgimento, and “Death in Venice” recreates the decadent ambiance of upper-class Europe at the start of the twentieth century.

Critics have praised the manner in which these big-budget films manage – unexpectedly and almost illogically – to blend an opulent, operatic sensibility with a documentary filmmaker’s eye for gut-punching realism. The former springs from Visconti’s own aristocratic childhood, which included regular attendance at La Scala in the family box.

But Visconti’s unflinching search for realistic nuance has its origins in the very first film he directed: “Ossessione (1943).” This lower-budget, black and white effort is set in the everyday reality of contemporary regional Italy. The film’s protagonists are an unremarkable man and an ordinary woman. As such, “Ossessione” is an early landmark of the emerging neorealist style that in the post-war period would become synonymous with Italian cinema.

Because “Ossessione” is not an elaborate period piece, but a gritty prototype of Italian neorealism, one expects that its use of operatic music will respond to exigencies that differ greatly from those of Visconti’s later and grander productions. This is indeed the case.

The film presents a love triangle. Giuseppe, a provincial boor, runs a filling station in the bleak countryside outside Ferrara. He offers little in the way of real affection to Giovanna, his lonely and much younger wife. When an earthily handsome drifter named Gino happens along, passion between Giovanna and Gino flares (Visconti’s depiction of their lust is realistic and frank, but never vulgar.) Though tempted to run away with her new lover, Giovanna soon loses heart and resigns herself to the loveless marriage that is her lot. Angered by her lack of resolve, the restless Gino finds the strength to leave and heads off alone to the city of Ancona.

If the plot sounds familiar, it’s because Visconti based “Ossessione” on a 1934 novel that Hollywood would soon remake, using the book’s original title: “The Postman Always Rings Twice.”

A coincidence brings the film’s three protagonists together a second time. Though loutish in other ways, Giuseppe nourishes a passion for opera. He takes his wife on holiday to join an amateur singing competition – as fate would have it, in Ancona. The couple again encounters Gino, whose love for Giovanna now reignites even more intensely than before. As the competition begins, the local amateurs perform arias that Visconti selects to add poignancy to actions that will soon move toward a tragic conclusion.

The director sets the competition on a makeshift stage in a noisy restaurant. Two contestants perform arias by Bizet. First is the “Habanera” from “Carmen.” The melody’s initial chromatic descent famously evokes Carmen’s sexual capriciousness: she both flirts and provokes, simultaneously inviting and rejecting love. A local woman, complete with fake rose in hand, sings the aria respectably. But her lackluster rendition, like the homemade full-length costume she wears, is blandly devoid of sensuality.

The second aria is “Je crois entendre encore” from “Les Pêcheurs de Perles,” in which the protagonist Nadir recalls the passion of lost love. The text speaks of an almost unbearable nostalgia, and the aria’s ostinato bass motif conveys the depth of Nadir’s longing to recapture the past. Here again, the singing is respectable but uninspired. A white-haired tenor, done up in a borrowed tuxedo, wrestles (in close up) with problems of intonation, and in the end, only barely manages to bring off the performance.

After Giuseppe hurries to take his place onstage, Giovanna is free to sit down at a table with Gino. Though clearly still attracted to him, she mocks his rekindled passion. Carmen-like, she puts out mixed signals, laughing and flirting ambivalently. As we watch her tease with looks and smiles, we realize – with the “Habanera” fresh in our ears – that Visconti has deftly identified Giovanna with Bizet’s heroine. At the same time, however, our recollection of the amateur Carmen’s lifeless performance stands in contrast with this moment of truly sensual love-play that Giovanna is now acting out.

The merciless flirtation hits its mark. Gripped by the anguished memory of their fierce lovemaking, Gino imploringly asks, “Do you ever think of me?” and begins to reveal the depth of his emotional dependence upon Giovanna. With the performance of “Je crois entendre encore” still in mind, we realize that the aria’s nostalgic yearning has prepared us to appreciate fully Gino’s tortured state of mind. Moreover, the discomfort we felt watching the middle-aged amateur grapple with the aria’s technical demands has conditioned the discomfort we experience now, as Gino struggles desperately to win back Giovanna. Thus Visconti invites the viewer to pity the Everyman who risks failure, both in art and in life.

By mirroring the contestants and the protagonists, the director has highlighted the absurd difference between the “love” experienced second-hand, at the removed level of amateur opera, and the authentic love that builds tragically between Giovanna and Gino. This is what fascinates: Visconti debases the experiential power of opera when performed by superb artists, and instead casts the scene’s musical parallels in the uneven efforts of a tawdry local competition. The stock poses and amateurish gestures made by the singers contrast sharply with the tense gazes and natural body language of the real lovers. The contestants have pathetically decked themselves out in overly-formal costumes, but Giovanna’s simple V-neck dress emphasizes a natural sensuality, and Gino’s workaday clothes signal authentic virility.

This is Visconti’s trenchant sense of irony, born in the opposition of parallel realities, at its most delicious.

When husband Giuseppe finally sings, his choice of “Di Provenza” from Verdi’s “La Traviata” brings the sense of contrast to a deeper level. Traditional in form, the aria is a father’s plea to his son to break from an “immoral” relationship; it identifies Giuseppe with a famous operatic father who is old, conventional, and unsympathetic to true passion. As we see the unfocused image of Giuseppe singing ardently in the background, we watch Gino seethe with growing anger at the still ambivalent Giovanna. His emotions boil, and when he knocks over a glass, it shatters and disturbs the cuckolded Giuseppe’s performance – a realistic detail that heightens the disparity between the boringly pious husband and the lustful young lover.

The pale, dark-haired singer whose performance follows Giuseppe’s is the most ludicrous of all. He takes the stage and warbles the first part of Verdi’s exquisite duet of seduction, “È il sol dell’anima” (from “Rigoletto”), to a motherly old woman with a cane. These unlikely onstage “lovers” provide humor in the Pirandellian sense of the word, in that we are both drawn to and repulsed by what we see and hear. But they serve a purpose. As the tenor rolls his eyes in an exaggerated imitation of conventional melodrama, painfully drawing out the rising pitches of the aria’s climactic lines (“Adunque amiamoci, donna celeste ”), Visconti cuts to a close up of Giovanna that offers a profound reversal of image: with only a terse half-smile and the smallest of eye movements, she lets Gino know that his baring of soul has moved her, and she is ready to commit fully to him.

Again, what dazzles is the ironic contradiction: while the amateur concludes his pitiable performance as the seductive lover from “Rigoletto,” Giovanna herself yields finally and unambiguously to Gino. The moment is at once comic and deeply persuasive: Visconti appears to ridicule the very act of sexual seduction, even as he reminds us of its power.

At the table, Giuseppe rejoins his wife and begins to drink heavily in celebration of his well-received performance. All three protagonists then leave the scene of the contest to make their way back toward Ferrara.

In the parking lot, Giuseppe stumbles and drifts into the oblivion of drunkenness and self-satisfaction. As he continues to sing snippets from “Di Provenza,” Giovanna and Gino resolve to murder him that very night. Ironically, Giuseppe croons the aria’s climactic phrase “Dio mi guidò” (“God has guided me”) even as Giovanna kisses Gino, and speaks to him the few decisive words (“Subito, capisci? Subito!”/ “Now, understand? Now!”) that signal their commitment both to the crime and to each other.

At this point, some 10 minutes have passed since the film has used any musical commentary other than the diegetic singing we’ve heard from the contestants and their pianist. But when Giovanna finally kisses Gino, Visconti brings non-diegetic music back to the soundtrack: a full orchestra plays a burst of descending phrases that offer no strong sense of tonal center. With this shift, the director returns music to its role as external interpreter of the plot. The chaotic nature of the orchestral music throws into high gear our sense that with their kiss, Giovanna and Gino have lost emotional balance, and have set their own downfall in motion. (Indeed, by the end of “Ossessione,” Giovanna will also die, and the police will arrest Gino for the murder of the hapless husband.)

Still, the film’s unique achievement remains Visconti’s placement of the arias by Bizet and Verdi in the mouths of the four amateur singers. With this technique, the director has amplified our understanding of motive and plot from inside the scene itself. This kind of narrative and intertextual richness will go on to characterize almost all of Visconti’s cinematic work.

Categories

Opera Meets Film