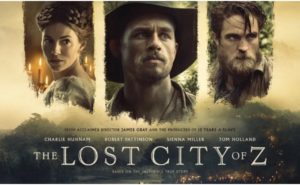

Opera Meets Film: How Operas By Mozart & Verdi Depicts European Colonialism in ‘The Lost City of Z’

By David Salazar“Opera Meets Film” is a feature dedicated to exploring the way that opera has been employed in cinema. We will select a section or a film in its entirety, highlighting the impact that utilizing the operatic form or sections from an opera can alter our perception of a film that we are viewing. This week’s installment features James’s Grey’s ‘The Lost City of Z.”

“The Lost City of Z” is an adventure film about a man obsessed with finding an elusive city in the Amazon that predates written history. His quest, while portrayed as heroic, also suggests the darker qualities of European colonialism.

It centers on Percy Fawcett’s legendary explorations through the Amazon in search of the elusive City of Z and the film manages to establish a constant contrast between the “savages” in the Amazon and the “savagery” of Western Civilization. This is best established in how Fawcett’s greatest foes from the start of the film, until the very end, are the British people that undermine his rank, his quality, and his ambitions.

His second journey through the Amazon fails not because of his differences with the “savages” (who take him in and give him hospitality), but because of James Murray, a self-proclaimed English explorer who burdens the expedition. At another point, the film highlights World War I and emphasizes how it is tearing the world apart. Jack Fawcett, Percy’s son, even tells his mother how he is likely to find more fulfilment in the Amazon than in the uncertainty of Europe after the war. While we do see the natives attack Fawcett’s crew on several occasions (and at the climax), their actions pale in contrast with that of European “civilization.”

Director James Grey furthers this sense of common humanity and civilization through the use of music. Early in the film, we see the Fawcetts at a grand ball in which we see everyone dancing to Waltzes. It is all an elaborate staged event with specific rituals that everyone invited is expected to follow. Fawcett lets his wife know early on that he is there because he needs to be. It is not for enjoyment but for mere ceremony to help him get an opportunity at advancement. It’s theater.

So it should be no shock that this similar theatricality is depicted when Fawcett has his first encounter with a “civilized” town in the Amazon. As he and Henry Costin arrive, we hear opera in what seems to be a non-diegetic means. The film has already introduced Ravel’s “Daphnis et Chloé” Suite No. 2 as a leitmotif of the film, so when echoes of Mozart’s music suddenly appear, it has the same haunting feeling. The music is from “Così Fan Tutte’s” Act one finale, calls out to European society.

But then we realize that this performance is in fact taking place on this small village in the Amazon. It is a reminder of the legendary opera house in Manaus where Caruso famously performed. The film never explicitly names the opera house, but the connections are quite potent. But the significance of the opera here immediately recalls European society and even Fawcett, as portrayed with a high angle wide shot, looks shocked and fascinated at what he is finding. What’s more, the production of “Così” is portrayed in a traditional production that strengthens the ties with the world thousands of miles across the sea.

But it is all mere theatrically on a social level. It might be truly beautiful to find opera in the middle of the jungle, but can’t hide the fact that people mounting it are monstrous in their actions.

This is showcased one scene later. As he goes to meet with a Portuguese nobleman who owns a rubber plantation. In the background is a faint recording of “Di provenza il mar” from Verdi’s “La Traviata.” The entire conversation is full of racist undertones and emphasizes the European nobleman’s greed; it is perhaps the most tense scene in the film, alongside Fawcett’s confrontation with Murray at the Royal Geographic Society later in the film. The Portuguese nobleman tells Fawcett that he will help the mission because he anticipates that nothing will change as a result of it (Fawcett has been tasked with drawing up the hotly contested border between Bolivia and Brazil to avoid a conflict between the two nations). Opera thus becomes a constant reminder of Europe’s continued conquest of the Americas, and its imposed culture on the region.

This concept is further substantiated at the end of the film when Percy returns to this same settlement with his son only to find that the opera house has perished. In fact the entire settlement is nothing more than jungle. Once again, we hear faint echoes of the Act one finale “Eccovi il medico Signore belle” from “Così fan tutte.” They are ghost-like, harkening back to the music’s initial appearance and the feeling it created. In a shot mirroring his entrance into the opera house, we see a high angle wide shot of Percy and his son, the former’s disappointed expression a far cry from the sense of wonder in that initial scene.

“The jungle is restoring the balance,” Percy says in the next shot, emphasizing the fact the Europeans don’t belong there. Their culture is truly foreign to that of the Amazon, which thrives on its natural beauty and balance instead of the “civilization” which Percy is constantly seeking.

Sure enough, Percy is also eaten up by the jungle, his disappearance becoming legendary. The film showcases the natives capturing him and his son, though we also never see what becomes of them.