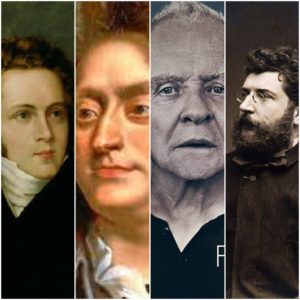

Opera Meets Film: How Opera is Used to Immerse Us Deeper into Anthony’s Mind in ‘The Father’

By David Salazar“Opera Meets Film” is a feature dedicated to exploring the way that opera has been employed in cinema. We will select a film section or a film in its entirety and highlight the impact that utilizing the operatic form or sections from an opera can alter our perception of a film that we are viewing. This week’s installment features Florian Zeller’s “The Father.”

As Anne walks down the street in the opening shots of “The Father,” we hear the iconic strains of Purcell’s ““What Power Art Thou” from “King Arthur.” It’s opening refrain reads:

“What power art thou, who from below

Hast made me rise unwillingly and slow

From beds of everlasting snow?”

The aria develops as Anne arrives at an apartment and then suddenly – the music is stopped by Anthony. We immediately learn that HE was listening to the recording on his headphones in his apartment.

What’s fascinating about this particular moment is what it seems to say thematically about the story and the characters and what is ultimately revealed throughout the rest of the story.

But another essential aspect of this aria’s introduction and presentation is how it is combined with two other arias throughout the film.

Later on in the film, we see Anthony in the kitchen. He turns on a radio that plays “Casta Diva” from “Norma,” in an iconic recording by Maria Callas.

For those unfamiliar with “Casta Diva’s” text, here it is:

“Pure Goddess, whose silver covers

These sacred ancient plants,

we turn to your lovely face

unclouded and without veil…

Temper, oh Goddess,

the hardening of you ardent spirits

temper your bold zeal,

Scatter peace across the earth

Thou make reign in the sky…”

Once again, the solo voice is singing out and pleading to a power outside his or her control. A power they can’t see but hope to know.

And halfway through the recording, Anthony shuts it off – another interruption.

A little later, we get back to Anthony listening to another aria, Nadir’s “Je crois entendre encore” from “The Pearl Fishers.” Nadir’s aria also speaks to a “divine rapture” and a “sweet memory” that’s almost unreachable, untouchable for the lonely man. And again, Anthony’s listening experience is uninterrupted, this time by the record player itself that jams up.

So what does this all mean in the context of the film? “The Father” is defined by cinematic interruptions, in the sense that it’s very narrative structure lacks cohesion for the audience and Anthony. We think it’s going in one direction until suddenly, it pivots in a completely different (and confusing direction). It’s all purposeful and meant to explore a subjective feeling of dementia and the disorientation it creates. As such, we, like Anthony, increasingly lose touch with what is going on around us, especially when we think we are finally getting a grip on the narrative developments.

And since this film essentially takes place within Anthony’s mind, the arias, in a way are his deep subconscious speaking to us. It’s no coincidence that he’s the only one listening to them in the film. And each one is a plea or even prayer to a higher power for some respite or grace. They all share a similarly melancholic and pleading quality. Anthony refuses to acknowledge his lack of control for the duration of the film. Time and again he asserts his sense of self, claiming that the apartment is his own, forgetting about his daughter’s death, claiming new identities for himself and his past. He is constantly rewriting his story from scene to scene as he tries to get a grip on his increasing powerlessness.

The arias seem to speak to him directly of the fact that he lacks power and it is no surprise that while he is shown “listening to them” inevitably, he is often the one to interrupt them, suggesting the fact that he is not in fact “listening” to them deeply and thus not in tune with his own inner voice and what it’s trying to communicate to him. This theme of listening could be further perpetuated in Anthony’s relationship to others in the film – he won’t listen to anyone. He refuses to. And because he won’t listen, he suffers.

The arias thus operate in this ambiguous space between communicating with Anthony in much the same way other characters attempt to do so, while also expressing his underlying powerlessness.

One cannot overlook the choice of opera either in the context of this film about an aging patriarch, a man whose time has passed and who struggles to maintain a grip in a modern world. Is that what opera is? For many, there is no denying that that kind of metaphorical parallel is not farfetched. And in choosing examples from the baroque, bel canto, and romantic eras, Zeller spotlights opera’s most prominent periods. It’s doubtful that Zeller is making a direct commentary on opera and how its lessening effect in the modern world, but there is a lot to be said for the fact that these iconic opera arias and performers are repeatedly interrupted.

Of course, the interruptions cease when all is revealed and clarified and the audience is allowed to know the truth. We do eventually get to hear the “Pearl Fishers” aria without interruption at the close of the film as we watch Anne leave the nursing home. There is no interruption because there is no lack of clarity for the audience any longer.

Categories

Opera Meets Film