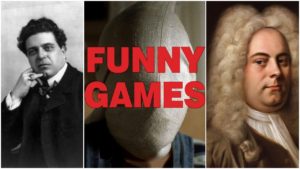

Opera Meets Film: How ‘Funny Games’ Prologue Uses Operas by Handel & Mascagni to Establish Major Themes of Comfort & Chaos

By David Salazar“Opera Meets Film” is a feature dedicated to exploring the way that opera has been employed in cinema. We will select a film section or a film in its entirety and highlight the impact that utilizing the operatic form or sections from an opera can alter our perception of a film that we are viewing. This week’s installment features Michael Haneke “Funny Games.”

As he often does in several of his other films, including “Caché,” Director Michael Haneke likes to implicate his audience in his films, often forcing us to live through the torturous “games” he puts his characters through. “Funny Games” is arguably the peak of this approach, presenting a film in which Haneke pushes the audience’s immersion to the limits.

The film charts the path of a bourgeois family as they head to their summer home for a nice vacation. Immediately after they arrive, a pair of young men invade their home and subject them to non-stop torture through some sadistic games.

Ironically, the “games” start right away with a god’s eye view from above of a car driving along the road. The soundtrack is ablaze with the duet from “Cavalleria Rusticana,” Georg and Anna playing a guessing game. She is asked to identify the singers, which she eventually settles on – Jussi Bjorling and Renata Tebaldi. Then she changes the tape and puts in her own piece of music – a recording of “Care Selve” from “Atalanta” featuring Beniamino Gigli. This time it is Georg’s turn to guess. He identifies Gigli and Handel, but can’t quite pin down the piece.

The entire sequence features the overhead camera angle with the voices and music playing over the soundtrack. Haneke is playing two games with the audience. On one hand, the voyeuristic shot following the car creates a certain discomfort to the audience. He is almost emphasizing the viewer’s distance from the story; we can’t even see the characters or make out where they are going. We just watch, almost as if we were Gods looking down on the characters. If you consider that he is the God of the story, creating the world and framing this shot from above, he is also emphasizing himself both as a cruel, but also powerless observer.

But Haneke’s contrasting use of sound (which plays a vital role throughout the entire film to fill in gaps where audience members can’t quite make out certain details or see certain things) contrasts the visual. While we can’t see Georg or Anna, we certainly feel involved in their story through their dialogue. And the opera passages take that step further – they provide comfort. The two selections seem to match the lushness of the outdoors surrounding the car. In that moment, the film suggests a certain tranquility that matches the laid back guessing game of the couple.

When Haneke finally relaxes this awkward juxtaposition and brings the audience’s eye into the car to connect with our protagonists, Haneke plays his dirtiest trick of all. Gigli’s soothing voice is suddenly interrupted by the shrieking tones of John Zorn. The audio blasts through the soundtrack, suddenly making the listener realize how comfortable he / she really was in that initial prologue. It’s almost an assault on the senses, an emotional invasion, especially when considering the fact that Zorn’s music has no place in the context of the scene. The “Cavalleria Rusticana” and “Atalanta” pieces were literally brought into the sound world of the film by the characters themselves. Zorn’s music freezes the frame and blasts over everything else and the disruption is meant to strike at the audience’s sense of comfort. It is chaos embodied.

This prologue perfectly encapsulates and frames the structure of the film with the two men invading the comfortable home of the family. The chaos of Zorn’s music provides an emotional counterpoint to the structure and relative calm of the two operatic pieces, further forging the dynamics of the characters that will take over the thriller.

What’s more, Haneke has already primed the viewer for the emotional shock he or she is set to subject him or herself to with this prologue, as direct a confrontation as any that he delivers in the entire picture.