Opera Meets Film: How ‘Colette’s’ Use of Bizet & Gounod Toys With Audience Expectations

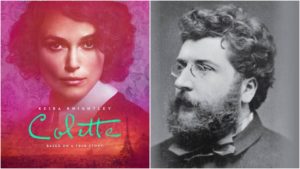

By David Salazar“Opera Meets Film” is a feature dedicated to exploring the way that opera has been employed in cinema. We will select a section or a film in its entirety, highlighting the impact that utilizing the operatic form or sections from an opera can alter our perception of a film that we are viewing. This week’s installment features Wash Westlemoreland’s “Colette.”

“Colette” is a biographical account of a woman rebelling against a patriarchal system to seize control and give herself the importance that she so deserves. That is she does so at the turn of the 20th century is perhaps what gives this film so much power.

So it is no surprise to see that the film’s two opera selections play up this theme of female power in the face of male dominance.

The arias, from “Carmen” and “Faust,” respectively, come during a sequence in the middle of the film, both working on a number of different levels. For starters, the choice of two French operas fits into the context of the film’s world – late 19th century and early 20th century Paris. Placing two operas from that period strengthens the audience’s immersion and belief that they are in fact in Paris; this might not seem like an important detail, except when one remembers that the film is completely in English and everyone knows, even subconsciously that the French at the turn of the century (and even today) will be speaking French with one another. It’s a minor detail but one aimed at serving the world of the film and strengthening our connection to it.

But the arias themselves are laden with meaning on a number of levels.

The first of these two is “Carmen’s” Seguidilla, the aria with which she seduces Don José in what will be an ill-fated romance for both parties. This aria appears when Colette heads over to visit American debutante Georgie in her apartment. It is blatantly obvious from a previous scene that Georgie has interest in Colette in a romantic manner and their first meeting alone in her home, with Carmen’s seductive theme playing, only strengthens this notion.

A few scenes later, the relationship has turned sour as Georgie has caught wind that Colette plans to include details of their salacious romance (Georgie is also engaged in an affair with Colette’s husband Willy). As they argue over how to handle the book launch, we hear Marguerite’s Jewel Aria from “Faust.” It’s an odd choice given the tense context and provides a bit of juxtaposition that will bear its meaning as the scene draws to a close. Georgie makes her masterful move and announces that the published editions of the book will be completely burned to pieces. Colette runs out and the climax of the Jewel aria comes to the fore, no longer just a diegetic part of the background, but non-diegetic and gaining priority in the soundscape. It’s almost as if Colette is celebrating the moment like a victory rather than a defeat.

As a viewer, we start to wonder at the use of the jubilant music in this seeming moment of loss for the protagonist.

But Westmoreland is actually setting us up for the next scene in which it is revealed that Colette and Willy will have the last laugh in this situation and will simply get the book published elsewhere. They are victorious after all.

It’s a clever choice and one that provides a unique contrast to the first operatic selection. Where the first one’s meaning overtly delineates the dramatic direction of its corresponding scene, this one actually subverts it, toying with the audience in much the same way that Colette toys with Georgie in the scene.

Categories

Opera Meets Film