Opera Meets Film: Comparing The Emotional Differences Between Kubrick & Moravec / Campbell’s ‘The Shining’

By David Salazar“Opera Meets Film” is a feature dedicated to exploring the way that opera has been employed in cinema. We will select a section or a film in its entirety, highlighting the impact that utilizing the operatic form or sections from an opera can alter our perception of a film that we are viewing. This week’s installment features the classic “The Shining.”

A few years ago, we took a look at the two contrasting approaches to Buñuel’s “The Exterminating Angel” and how the opera by Thomas Adès adapted it for the operatic stage. In this edition, we will embark on a similar exploration, but take a look at how Stephen King’s “The Shining” was showcased in both cinematic and operatic format.

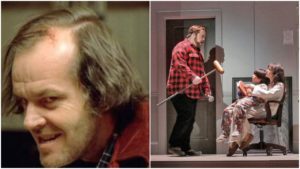

Stanley Kubrick’s film version of the work needs no introduction. It is one of the iconic horror movies of all time, known for its grating tension and a performance for the ages by Jack Nicholson.

But the operatic adaptation by Paul Moravec and Mark Campbell had its world premiere as recently as 2016 at the Minnesota Opera and has had few revivals since (our analysis here is based on the elusive 2016 recording of the work).

Love & Evil

Plot-wise, the two manage a general outline of King’s novel. The Torrances arrive at the Outlook Hotel where their relationship unravels until Jack turns on his family and nearly kills them; eventually, he winds up dead and Danny and Wendy Torrance manage to escape.

But it’s in the particulars where things veer off in decidedly different directions. Kubrick’s vision was famously called “a big, beautiful Cadillac with no engine inside it” by King himself and has described the approach to their main characters, including Jack and Wendy. Of the former, the famed author noted that there was no arc while the latter is “one of the most misogynistic characters ever put on film.”

But Kubrick’s vision is in line with much of his other work, exploring the coldness and darkness of humanity. The original work emphasizes that the Overlook Hotel is taking over and haunting the Torrance family, but the film, which explores its haunted nature, seems more intent on exploring the ghosts mainly through Jack and Danny’s own emotional trauma and fears. Jack unravels emotionally because it is in his nature to do so. And once he does, there is no turning back for him.

A maze plays a key visual part in the film, emphasizing the human mind’s own destructive nature. Once Jack gets caught in this maze of destruction, he can never escape it, as the film’s ending shows. In this version, Jack becomes the monster, killing off Halloran at one point.

Wendy, meanwhile, becomes more of a passive character, trying to come to terms with the death of her family with no real sense of how to save herself or her son.

The opera hues far closer to the original source material with regards to the original plot and its emotional themes. There is a clearer emphasis on the ghosts of the mansion attacking the Torrance family and becoming the antagonistic force, with the first act ending on a chorus of the dead appearing before the family and the story of the Gradys being revealed fully for them. At that point in the story, the family retains a united front with Jack and Wendy even getting a love scene between them early on. The haunting does not seize control of Jack until the second Act and that is when he starts to slowly fail in his task of protecting his family.

“One archetype I see in this story is a kind of Abraham and Isaac situation,” Moravec stated in an interview with Slate back in 2016, regarding how he viewed the character of Jack in the work. “Jack Torrance has two sets of instructions. One is to be a good father and a loving husband. The other is to obey orders from a higher authority to kill his son.”

From there, the family starts to fall apart until Jack eventually comes to terms with the situation and, in an act of sacrifice, saves his family and blows up the hotel within himself inside. As King had originally hoped, Jack becomes a tragic hero in this version.

Wendy meanwhile, is not such a passive character. In the film, Wendy stabs Jack on pure instinct, but the opera gives her a big moment (capped by a high note), that emphasizes the situation as an act of free will and decision from a character hell-bent on protecting herself and her child.

Finally, Hallorann, who becomes murdered in an act that cements Jack’s racism, survives in the opera and takes care of Wendy and Danny.

Thematically, the opera is about a family unraveling, but ultimately saved through sacrifice and love; the film is icy, much like its environment, with an emphasis on humanity’s own cold evil.

The Music

Music and pacing play a huge role in how these two works operate, especially with how operatic Kubrick’s films often feel.

The film’s glacial atmosphere is not only the result of its drawn-out and often repetitive pacing, but also its music. Kubrick returns again and again to the same pieces of music by Bartok, Ligeti, and Penderecki with a particular emphasis on string instruments and their extreme ranges. The music alone grates against the listener, adding to the heavy feel that the film already exerts on the viewer. The fact that this music returns again and again only adds to the exhaustion the film manages to cause.

Moravec’s music is also very string-heavy, which allows for a nice contrast with Kubrick’s score. The through-written approach in the opera actually creates a much faster pacing than Kubrick’s work (the opera clocks in at well under two hours, with the film closer to two-and-a-half hours in length). The music, despite being from the 21st century, also feels far more romantic in nature, adding to the warmth of its themes.

One interesting element of the opera is how Danny is interpreted. While he is key to the story both narratively and emotionally, musically, he doesn’t actually sing until much later in the work. The voice is the key to opera and having a major character without a musical voice for much of a work speaks symbolic volumes about his emotional agency in the score. And so when Moravec has Danny finally sing, it means something huge for the story.

His first big moment comes at the climax when faced with death at the hands of his father he sings “You are not my father.” This moment brings Jack back to earth and makes him realize all of his mistakes; his son’s greatest power isn’t necessarily the supernatural, but his ability to connect on an emotional level with his father and ultimately cause the sacrifice that will save his mother and him, but also his father’s soul. It’s a potent musical moment, especially since on first listen, the lack of a voice for Danny creates a unique kind of tension that builds up over the course of the performance.

Speaking of voices, voice types are also crucial in the opera. Jack and Hallorann are both baritones, which serves to unite them as foils for one another. While Jack becomes a corrupt father, Hallorann is the benevolent one. In the film, they played similar themes, though the racial dimension ultimately outweighed the dynamics. Moravec’s choice to create four tenor roles for those associated with the hotel (spirits and employees), emphasizes the “unnatural” nature of that particular voice type.