Opera Meets Film: ‘Citizen Kane’ Creates An Aria & Reinterprets Rossini’s ‘Il Barbiere di Siviglia’

By David Salazar“Opera Meets Film” is a feature dedicated to exploring the way that opera has been employed in cinema. We will select a section or a film in its entirety, highlighting the impact that utilizing the operatic form or sections from an opera can alter our perception of a film that we are viewing. This week’s installment will showcase “Citizen Kane’s” unique interpretation of the art form.

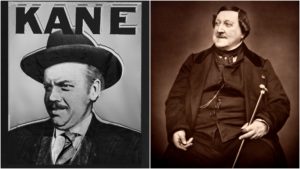

For many, Orson Welles’ “Citizen Kane” is arguably the greatest film in history. Its exploits are legendary, the film redefining the art form in its cinematography and approach to storytelling. It is the “textbook” film.

Those familiar with the film know that there is an extensive sequence dedicated to opera, specifically Kane looking to transform his second wife Susan Alexander into an opera singer. After they are married, Welles presents a scene in which Susan is asked if she is going to sing at the Metropolitan. Kane replies that “we will.” From here on, the entire opera sequence becomes more about Kane than Susan.

Rossini Upside Down

We see the opera sequence played out from differing perspectives, but the most interesting for the purposes of this article is Susan’s. She relates the challenges of trying to learn opera against her own desires, the film painting her as a woman that is not in the social stratosphere as her titanic husband (he builds an opera house for her). In one particular scene, she is rehearsing “Una voce poco fa” from “Il Barbiere di Siviglia,” an aria in which Rosina reveals her determination to do whatever it takes to get what she wants. The aria plays out rather ironically in the context of the scene where Susan has no idea what she is doing, her voice teacher is tired of trying to teach her and Kane ultimately forces them both to continue, despite that it is not a great idea. That opera also includes a lesson scene in which the “teacher (who is really her beloved Count Almaviva)” and Rosina team up to overcome Don Bartolo, who is forcing her into the lesson in the first place. That sequence is full of humor, the lovers ultimately overcoming the master. But here, the dissonance is everywhere between the three major players of the scene. Susan has no power and her position in the single shot of the scene bears this out. She is relegated to the right corner in the frame, caged in by the piano and other surrounding props to accent the discord between the content of the aria and the character portraying her. Kane meanwhile is a looming figure from the distance in the center of the frame, slowly walking toward the foreground and then plopping himself in the center between the teacher and Susan, his presence the most preponderant. It’s a subtle detail, but heavily effective and revealing to the viewer familiar with Rossini’s opera.

Tailor-Made For The Film

The film itself is based on the life of William Randolph Hearst though it diverges heavily in this sequence. Hearst was at one point engaged to soprano Sybil Sanderson, for whom Massenet wrote “Thaïs.” In the writing of the script, Welles and fellow writer Herman J. Mankiewicz had originally wanted to include the music of “Thaïs” for Susan’s opera debut. However, at the time of the film’s making the opera was still under copyright. So composer Bernard Hermann created an Ersatz opera “Salammbô.” The work is staged and Susan’s performance is fully developed in her recall of the sequence. Those who listen closely can even grasp the words of the aria which is a full-on lament, the soprano imploring the gods to strike her down. We don’t really know what she suffers of, but she ultimately dies at the close.

The aria, tailor-made for the opera, serves a potent dramatic function. The text of the aria breaks the “fourth wall” of the stage within the film. Susan isn’t just performing an aria, she is singing directly to the god who has put her in this dilemma. The aria repeatedly calls out for the “Cruel one,” which is exactly what Kane is for Susan. He has forced her into this anguished situation and because of him, her vocal career will die, just as the character does at the end of the scene. The constant edits from Susan singing onstage to Kane’s reactions only emphasize this idea.

It is interesting to note that the aria itself has been showcased outside of the context of the film. For example, Dame Kiri Te Kanawa recorded it and soprano Eileen Farrell performed it as an encore for recitals, often bewildering audiences.