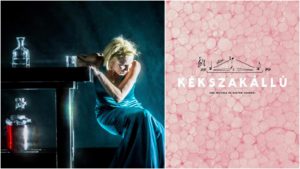

Opera Meets Film: Bartok’s ‘Bluebeard’s Castle’ Inspires Argentine Director’s ‘Kékszalállú’

By David SalazarWe are proud to introduce “Opera Meets Film,” a feature dedicated to exploring the way that opera has been employed in cinema. We will select a section or a film in its entirety, highlighting the impact that utilizing the operatic form or sections from an opera can alter our perception of a film that we are viewing. This week’s installment features an Argentine film “Kékszakállú,” by director Gastón Solnicki.

“Bluebeard’s Castle,” in Bartok’s iteration is a labyrinth. From the twisting and turning melodies to the increasingly strange and hallucinatory plot, the audience gets sucked into the world and then gets lost time and time again, quite possibly never escaping from its ever-looming spectre.

Apparently, this in part inspired the Argentine film “Kékszakállú,” a movie that follows a number of girls living out transitional moments in their teenage lives. During the course of the film, sections from Bartok’s score make appearances (four to be exact) bridging the connection between the two works.

And while opera lovers will recognize the opera’s non-diegetic intrusions into the film, one could easily come away wondering how they connect at all.

On the surface, the opera and film only really have one thing in common – female protagonists. That aside, the plots (or absence thereof) themselves nothing to do with one another. But a deeper look reveals far more than meets the eye.

In picking female protagonists, Solnicki is mirroring the oppressive qualities of a patriarchal society (the theme overriding “Bluebeard’s Castle”), showcasing his young women in “crisis” as they look out at their bleak futures in this sort of world. In “Bluebeard,” the fate of his wives is much the same and we know that despite her efforts, our protagonist, Judith, is not going to escape the same end.

Solnicki’s film also mirrors Bartok’s emotional structure in that while the Hungarian composer threw the viewer into a musico-dramatic labyrinth, Solnicki takes it a step further, showcasing a visual maze that traps the viewer and leaves him or her constantly looking for an answer, a way out of numerous strands that seem to hint at direction while being completely devoid of it. The characters themselves are directionless and much like our protagonists in Bartok’s opera, we don’t really know who they are and don’t learn all that much by the time the work comes to an end. One girl quits work and struggles to figure out what to study in college. Another is just hanging out and doing little else. Ditto for a few others. Like Bartok’s opera, we are constantly challenged about what we are seeing (and hearing) and our own minds begin to be driven mad by what at times might seem incoherent. As with all story, we search for direction and catharsis, and just when we think we are on a path toward it, Solnicki rips it away from us.

The inclusion of Bartok’s score in this film only adds to that sense of disorientation. In a film devoid of music for lengthy portions, the sudden arrival of operatic voices and Bartok’s mysterious orchestral harmonies add to the sense of darkness and inner turmoil that these characters are struggling with. We feel a sense of oppression in their world, the likes of which comes with mundanity and overall societal complacency. At one point, a section with a repeated triplet figure makes an appearance, its yearning accenting the images of characters lost in their worlds. The haunting figure nags at the viewer, creating a greater sense of unease that is only heightened by images jumping around from a school to a home to a theater, with no overt sense of purpose.

Watching this film is no easy experience and mirrors the feelings of watching Bartok’s opera. In the same way that Bluebeard’s wives all endure a dark existential fate, the girls in this film also seem to be prisoners to the oppressive world of Argentina. And we, in both opera and film, are also prisoners subjected to a similar emotional experience.