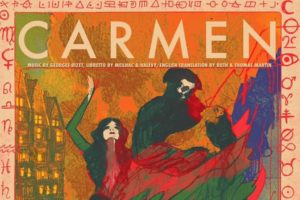

Opera in a Box 2022 Review: Carmen

A Well-Conceived Production Breathes Fresh Life into Classic Masterwork

By John VandevertOn February 20th, touring southern UK opera company “Opera in a Box” performed its second of six performances of Georges Bizet’s best-known operas “Carmen” to a packed black-box theater within The Station in Bristol, UK.

With a cast of mostly young and early-career singers, accompanied by a single pianist and subsumed in transfixing lighting arrangements by a modest crew of one, Opera in a Box’s deconstructed and DIY-educated interpretation of “Carmen” expertly teeters the line between G&S comicality and operatic sophistication.

Bridging the divide between the opera lyrique style and the burgeoning verismo of the late-19th century, Georges Bizet’s ninth and final opera Carmen, premiered in 1875 to undeservingly cold reception, is a harrowing tale of the acidic kiss of fate, the same kiss which befell Verdi only 10 years earlier with his 25th opera “La Forza del destino” and then again with Carl Orff in 1937 with his deafening cantata “Carmina Burana.” Fate, with her kisses and her daggers, isn’t someone far from opera and is instead practically interwoven within every opera past and present, as the very human desire to eschew the premeditated inevitable with the blithely pleasurable present is nothing short of miraculous.

As if by fate, such a compositional pull towards the authentic was directly invoked in Opera in a Box’s production of “Carmen,” where black-box seating and deconstructed set pieces, intimate lighting and interactive singers blurred the lines between life and opera, while the parochial hierarchy of performer and performed-for was cast aside for a living, breathing alternative.

Intimacy Abounding

As someone who is relatively unaccustomed with the “intimate” variation of operatic performance, being instead more familiar with the “find your seat and become another face in the sea,” Opera in a Box’s approach towards expanding accessibility to opera is a novel one indeed. The relatively young company, founded around six years ago, is led by a desire to bring operatic experiences to new audiences through “innovative staging, immersive performances” as Creative Director Charlie Morris explained to me prior to the performance. The reigning issue still plaguing the opera genre, although in recent years it is greatly improving via grassroots community-focused initiatives such as these, is the need to change the idea that opera is an elitist pass-time enjoyable only by those in possession of musical knowledge and isn’t designed for the workman, the banker, the nurse, the everyday citizen. Like Morris emphatically stated and to which I agree, “Opera is for everybody!”

The ingeniousness of Opera in a Box’s performance was its Lehrstücke ethos, a term coined by German playwright and poet Bertolt Brecht to describe his technique of obscuring the harsh dichotomies of actor-audience and refreshing the form-content contention with the idea of “function.” The tired framework was retired and the “modes of production” were married to the “workers” themselves, and the alienation incurred by the fourth-wall was exploded, the audience instead being subsumed into the world of the characters. The singers then became archetypes for states of social relations and the music but intoned subtextuality for the human layer lying within every action on-stage. Despite the cast’s varied levels of vocal mastery and actorial expressivity, it was clear that the future of opera may not lie in continuing to beat a dead horse with bells and whistles of theatrical pageantry but instead use more wall-destroying methodologies instead! Curious as it is, when the support beams of an opera are more visible to the audience, the viewing experience actually gets stronger as we know how its being made.

So if intimacy and laying bear the skeleton of productions are to be foregrounded as the next “new thing” in operatic productions and staged performance, then Opera in a Box is a seminal player in making that a concretized reality. By forcing the audience to “hear,” not only musically but holistically, the world the opera is trying to create gains a palpable dimension which transcends the barriers of mere spectacle and enters the realm of life. The way to do this, however, is not always clear but with Opera in a Box they chose to foreground intimacy in a new and interesting manner. Just like “Carmina Burana” and its cyclical structure, where the beginning and the ending use similar music and names in order to insert a meta-structural irony into the whole work, so too did Opera in a Box chose to present this layer as the presiding tenant of the production. Right when you walked in, director Marianne Vivash presented the audience with a matchbox set complete with two actors already on the stage (Carmen and Don Jose), although what they are doing (Carmen on the ground after being murdered and Don Jose standing over her in despair) is not entirely clear until one starts to piece together the clues. It is this “build-your-own experience” that immediately drew me to this style, as no other performance I’ve been to is so explicitly cryptic when dealing with the subject of fate and fortune. Once the curiosity of the moment wore off and the opera began, the Lehrstücke aesthetic began diversifying its technical embodiments. I could see actors entering and exiting, waiting for their turn to come onto stage, singing from beyond the demarcated staged zone, holding the curtain open, even trip over a box at one point. These types of humanization of opera is exactly what made this production so magical, as I wasn’t just seeing another production of Carmen but humans putting on an opera of Carmen for other humans. As axiomatic as it may sound, one gets caught in an illusion of grandeur when going to operas at the MET, La Scala, Covent Garden, hell even the Hippodrome here in Bristol. You stop seeing the performers as flesh’n’blood people and more so highly-educated and talented strangers who are at your behest for (fill the the amount of time).

The fourth wall has its place but when it comes to opera, I want to see human beings not empty machines.

Some Thoughts on Singing

I was pleasantly surprised to see that despite the “student” ethos of Opera in a Box the vocal side transcended that by a landslide. Most of the cast, when you look at their biographies, have significant achievements under their belt and those who are newer to opera certainly do not present as novices.

In the title role of Carmen was recent graduate Gigi Strong, a first-time singer with Opera in a Box whose achievements extend from verismo to musical theater. A technically strong mezzo soprano, with a well-developed range from head to toe and a latent dexterity just waiting to emerge, Strong’s portrayal of Carmen proved Bizet’s adept ability to coax out of singers dramatism without the sacrifice of bel canto to do so. Most prominent was her lower register, whose heft didn’t go unnoticed by more than a few audience members around me. This was especially prominent in Act one Habanera, or by its accurate name, “Love Is a Rebellious Bird,” where Carmen sings of the untrappable nature of love, its inability to be properly governed, invoking the opera’s ominous idée fixe “If I love you be on your guard.” While lacking in volume and timbral richness at times, along with much of Carmen’s body language and searing allure useful in really selling this one-octave aria, Strong’s interpretation seemed if not the best then solid overall. Her robust chest voice and growing upper register will be interesting to watch, as it holds much potential. In Carmen and Don Juan’s Act one duet “Near the walls of Seville,” the provocative mystique and seductive entrapment that is supposed to imbue the entire scene was simply not there in voice or body for either singer. Nevertheless, her softer yet commanding voice had a pliability that will presumably only mature with age and experience. Plus, her ability for musical nuance is already!

In the role of Carmen’s unwavering lover Don José was the leggiero tenor Robert Felstead, whose extensive repertory leaves one a bit confused as to the classification of his lyrical yet dramatic instrument. Felstead was a confident and demonstrably capable tenorial singing-actor, although at times his upper register was a bit strained AND yet in the heat of emotion his Wagnerian aptitude and unceasing musicality showed itself. That being said I found myself not entirely convinced nor satisfied with his overall approach, especially in moments supposedly intimate, more melodic, or climatic in nature as was the case during the Act one duet with Micaëla, Act two duet with Carmen, and especially Act three duet with Escamillio. While capable of higher notes and somewhat capable of the middle-register lyricism required of the leggiero, Felstead fell on tough footing in recitatives with staying in tempo and fully committing to the textual cadences, although I blame English for this as in French, the music matches the cadential patterns of the language perfectly. But as the opera progressed, I noticed that Felstead began taking dramatic risks with his acting and when this switch occurred so did his voice as well. This paradigm shift was most pronounced in the opera’s climax and its most intense moment, the duet “C’est Toi? C’est Moi!” In this lengthy scene Felstead gained a vocal clarity and acting temerity which had been all but unseen throughout the entire rest of the opera.

In the role of Escamillio, Carmen’s “lover” and tenacious torero of Seville, was Opera in a Box’s Artistic director Charlie Morris, an exuberant and cavalier baritone whose confidence was a refreshing breeze within the show. While not the most technically masterful singer on-stage, that mattered little as his braggadocious air and flirtatiousness made it so that any falters in the voice became characteristic of his telling of this complex character. The only real “show-stopper” this role gets is the ubiquitously quoted (and quotable) Act two aria “Toreador,” an aria which quickly captured the public’s ear practically as soon as it was first heard back in the 1880s. So decadent is Escamillio’s profession of stardom that it’s said that Bizet was rather nonchalant about it, as the public vyed for excitement and he dispassionately provided it. That disjunct layer of excitement and loathing, present within the aria’s first audience who responded to the aria with “coldness,” was also rather apparent in Morris’s performance. Swagger and playing to the gallery is fine, but when paired with wavering musicality and a lack of inflectionary spice, there is not much to be done. The music sits within a very small range and is incredibly repetitious, leading to a lack of newness causing many baritones to exaggerate their acting and sacrifice nuance in the process. That being said, the confrontational Act three duet with Jose (I am Escamillio, the toreador of Grenade!) was much improved across the board, although again Morris has a tendency to go tonally sharp and sacrifice prosody in order to focus on dramatic depth, a mobile balance difficult for any singer let alone one in the heat of vocal battle. In moments of connection with Carmen, his bel canto voice came through and with incredibly consistency, leading me to believe that it wasn’t a lack of technique necessarily but in-scene excitement which was leading to the pervading habit of raising the pitch slightly and the sacrificing of musical gestures, archetypal for a baritone of his status. It’ll be interesting to hear him in oratorio and more temperate conditions, as it’s evident he has an innate lyricism to the voice that certain roles do not yet showcase. I would love to hear him with Bach!

Wanting More

However, in the cast were two exemplary young singers whose already full careers leaves me wanting more of their voices.

In the role of Micaëla was the lyric soprano Hollie Anne Clark, although with her phenomenal dramatism in her upper range and unmatched lyricism, referencing not its modern iteration but the true form of bel canto as first taught by Bernacchi and Marchesi, I wouldn’t be surprised to see some heavier roles in her future. Throughout the entire opera, beginning with her first blush on stage in Act one’s “Tell me about my mother,” Clark’s magnificent voice was on full-display if only for a passing but protracted moment. Without sensationalizing the mood, by far the greatest point in Opera in a Box’s production was Clark’s Act three aria “It’s the smugglers the ordinary refuge,” where a sublime hush overtook the entire black-box theatre so Clark, scared and alone with nothing but the grace of God and the sweetness of her love guiding her, could rhapsodically plead with Providence to reconvene her with José. To say well done is an understatement and I trust my readers will recognize that true artistic exceptionality cannot be accurately portrayed in words alone. The air after she finished was not the same for a long time after.

Then there was Frasquita, sung by the dramatic coloratura Rebecca de Coverly Veale. A criminally underutilized voice in this production, Veale’s vocal tenacity when it came to the chorus descants and her unshakable histrionic acting would have made a daring Carmen. Regardless, her flexible yet fully solid instrument ached for more pathos-laden roles like Violetta or Norma perhaps and I look forward to hearing her in the spotlight when the time comes.

Keeping the whole production musically together was Opera in a Box’s Musical Director Sam Baker, a well-decorated and highly educated pianist and organist (among other titles) whose biography, not provided in the program I might add, displays a breadth of knowledge far surpassing what was showcased in the performance. Having gained education at Oxford University, before venturing into Europe and returning home again, one would conclude that color, expression, and prosodic astuteness would be at the forefront of his musical language. However, at times his playing of the score escaped time-signatures, the clunkiness of the electronic piano was anything but sensual, and I didn’t really feel that the singular pseudo-piano did any justice to the magnificence of Bizet’s score. Although no fault of his own, as one video on YouTube of him playing Satie’s gaseous Gnossienne No.1 will attest, when given a full instrument he is able to intone emotion into every tone. However, because of the piano’s metallic ring emotion was rather hard to “hear.”

Overall, Opera in a Box’s production of Carmen was a very solid performance from the entire cast and an encouraging sign that opera has come quite far in returning to its roots as a “people’s art form” as was the case not too long ago. Those who say that attainable opera is connected to poor quality are naysayers to the future of this historic art form. Opera in a Box is anything but stuffy and the world is greater for it! I highly recommend going if you find yourself free on evening in Bristol.