Opéra de Lyon 2018-19 Review: Mefistofele

No ‘Olés’ for Àlex Ollé’s Latest Attempt To Explain The Legend Of Faust

By Jonathan SutherlandThe old Irish proverb “Better the devil you know than the devil you don’t” is particularly applicable to Barcelona-born director Àlex Ollé.

Without insinuating any untoward obsession with Satan, in the past ten years Ollé has had numerous dramaturgical dalliances with the Prince of Darkness. First was the cutesy “[email protected]” in collaboration with Fura dels Baus co-director Carlos Padrissa. In 1999, Team Ollé/Padrissa staged Berlioz’s “Damnation de Faust” at the Salzburg Festival to rave reviews.

In 2001 there was a film version: “Faust 5.0” suggesting Ollé has not only a preoccupation with Goethe’s epic narrative, but an actuary’s fondness for decimal points. Gounod’s “Faust” was given an Ollé makeover in Amsterdam in 2014, then earlier this year Stravinsky’s Faustian oeuvre “Histoire du Soldat” came under the Spanish director’s microscope.

A Modern Faustian Take

In his programme notes for Opéra de Lyon’s new production of the Arrigo Boito’s rarity “Mefistofele,” Ollé explained that after so many previous interpretations, the character of Faust no longer held much interest. Too bad for Marlowe and Goethe. It was more the Iago-evil inherent in the character of Méphistophélès which now sparked the Catalan’s curiosity.

The venerable scholar, wracked in a Szymanowskian conflict between Apollian and Donysian duality, was virtually an incidental participant in a rather tedious narrative of Satan’s impenitent cruelty and implacable capacity for evil. In a work originally concerned with the conflict between God and Satan, or at least Good and Evil with a healthy dose of Catholic absolution thrown in, there was actually minimal spiritual or religious content in Ollé’s mis-en-scène.

Instead of a prominent bible in the laboratory scenes motivating Faust’s emphatic “Baluardo m’è il Vangelo!” he casually surfed the web on his MacBook Pro. It is unlikely www.holybible.com was even bookmarked.

An army of angels costumed by Lluc Castells wore enormous white feathers and Airbus 380-sized wings over radiation-proof jumpsuits. They looked like a fusion of June Taylor dancers and an outré Lindsay Kemp drag show for alated astronauts. There was no grey friar’s habit or dashing chevalier couture for Satan – instead, he sported a sterile yellow janitors uniform, spivvy black shirt and trousers and a tight-fitting singlet which made the personification of Evil more like Rocky in permanent pugilistic mode. There was no cape with which to provide port-key like transportation. When Faust asks “Come s’esce di qua?” Mefistofele replies “Pur ch’io distenda questo mantel noi viaggeremo sull’aria” but there was only a shabby T-shirt in Beelzebub’s wardrobe.

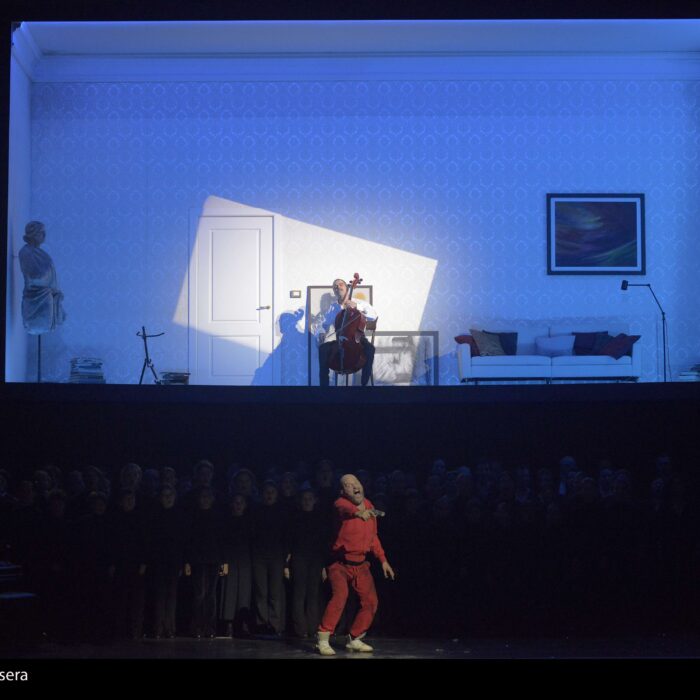

Alfons Flores’ two-tier stage designs were reminiscent of Robert Lepage’s capricious mechanical contraption in the Met’s latest “Ring” production and there were metal girders, trapezes, steps and stays dominating the large stage. Instead of cloudy celestial heavens, the Prologue took place in a multi-desked laboratory/schoolroom which had more to do with vivisection experiments than philosophical contemplation.

The Domenica di Pasqua could have been a boozy office party straight out of “How To Succeed in Business Without Really Trying,” complete with sozzled secretaries gyrating out of time. There was a further tasteless syllogism in the prison scene when Margherita is moaning dementedly about her miserable past and reflecting on the un-cool deeds of poisoning her mother and drowning her newborn baby. During “Il mio bimbo hanno gittato” a lackey appeared with a silver-service repast. The cloche came off to reveal a barely formed fetus with extended umbilical cord as if Margherita had spawned an amphibious sprog.

A Boring Devil

The single directional focus of Mefistofele as a psychopathic misanthrope and serial murderer meant that psychological interest in the much more fascinating Faustian character was thoroughly extirpated. As a way of explaining Mefistofele’s anarchic malevolence, Ollé had some particularly vicious angels tear out Satan’s heart in the Prologue, but as the Devil is immortal, there was obviously no real harm done.

This mono-dimensional Mefistofele did some particularly mundane things in furtherance of his chronic turpitude. In the Prologue, Satan complains that ubiquitous cherubim and seraphim buzzing around are as annoying as a swarm of bees (“come dell’api n’ho ribrezzo e noia”) but his irritation suddenly became violent and he strangled a few stragglers to prove the point. So much for the nifty “no hands” powers of Lord Voldemort’s Avada Kedavra curse.

Ollé also put a novel twist to the dénouement as Mefistofele actually slits Faust’s throat. Unfortunately, this conceit made nonsense of Faust’s deserving redemption but also inferred the omnipotent Demon needed a mere mortal’s dagger to dispatch his former acolyte.

Not Much Better

Vocally things were not much better although the smaller roles of Martha/Pantalis and Wagner/Nereo sung by Agata Schmidt and Peter Kirk respectively were satisfactory.

Russian soprano Evgenia Muraveva enjoyed success in Salzburg this summer as Lisa in “Pique Dame” but on this occasion made minimal impact as both duped virgin and glamor-puss Goddess. The voice has a creamy coloring but tends to pinch at the top and her diction is desultory. The Garden scene was never more than perfunctory with insufficient lightness in “La fanciulla del villagio.”

The Prison episode was better sung with some gossamer phrasing on “vola, vola, vola” and a commanding crescendo on “delirare” although the E-flat trill was not as pristine as that of first flute. There was better word coloring in the parlando passage “Ed ho affogato…il fantolino mio” and the forte top B-natural fermata on “Ah” before “Questa moribonda perdonerai” was Freni-esque.

Muraveva seemed more comfortable as the louche Elena, and the opening of Act Four was appropriately “languidamento espressivo.” “Notte cupa, truce” was ominous with a hefty sforzando on “al vento” but the top B-flat after “Ahimè” was tentative. The soaring “Amore! Misterio celeste” duet was as incandescent as a slice of soggy baklava.

Not Quite Heroic

Faust was sapped of cerebral curiosity in his dotage and neutered in his nefarious youthful transformation. Physically there was no change at all between hermit/philosopher and dashing ne’er-do-well. Not even his comb-over coiffure à la Trump changed. The only nod to a new hip persona was an Elvis-ish black-spangled jacket which looked decidedly odd over his prosaic polyester striped tie.

Physically Paul Groves looked alarmingly like Monsieur André in “’Allo, Allo” complete with a thin limp mustache. The American tenor sang Faust in the Ollé/Padrissa Berlioz “Damnation” in Salzburg in 1999 to rather muted enthusiasm. Nearly 20 years later the voice can hardly be described as in its first bloom and blandness in acting matched the singer’s vocal anemia.

That said, there was some sensitive phrasing and commendable mezza voce in “osserva come fulgoreggian a vespro” and a finely controlled piano diminuendo legato on “ritorno e di pace’ in the “Dai campi” aria. “E l’ideal fu sogno” in the Epiloque had impressive pianissimi reaching a solid A-flat on “Si bea lamina già, in un sogno supremo” with a honeyed tenore di grazia timbre. Similarly, the subtle word coloring on “Vo’che surgano”and crisp acciaccatura on “dell’esistenza mia” reflected the impeccable vocalism of Groves’ former teacher Alfredo Krauss.

However, almost everything above G natural was pushed, bleaty or rapidly disengaged. From the first F-sharp on “primavera” and hesitant G natural on “speranza,” it was clear that the top register was going to be this Faust’s fatal flaw. Even the F-sharps on “fuggente” and “cantatrice” in Act Four were pushed and labored. The top B-natural fermata on “Amor! Miserio!” was reticent and the chromatic step to A-sharp ending the “nessuno, nessuno” passage was senza crescendo. The high B-flats on “innamorato” and “conquiso m’ha più” in Act Four were barely proximate and the climatic B-natural on “Vangelo” thin and parched. “Margherita, l’angelo mio” had the ardor of Faust contemplating his tax return.

No Salvation Here

Perhaps due to his janitor’s uniform and working class black singlet, John Relyea’s Mefistofele was decidedly alluvial. There was certainly a booming, fog-horn projection in the lower register such as the G-flat’s on “il Male” and “morte e Mal” but overall diction was blurred and attack more hooty than honeyed. From his first “Ave, Signor, perdona se il mio gergo,” there was plenty of contempt but not much cantabile. Diction in the Prologue and “Al Brocken” scena was entirely unintelligible. The top was generally pushed such as the F-natural on “Ah Si” in the Prologue and on “il mondo” at the end of the “Ecco il mono” scena and the top E-flat on “Vuota dovrò serrar” in the Danza di Streghe was thin and constricted. Points for perniciousness but demerits for delicatezza.

Rustioni Arrives

Happily, the limitations of the dramaturgy were redeemed by excellent chorus singing on the stage and the magic wand of Daniele Rustioni in the pit.

Opéra Lyon’s enormously talented Musical Director was basically faithful to the integrity of the partitura except for two small cuts in the “un giorno nel fango mortale” music for Cherubini in the Prologue and a further excision for Coretidi (“Chi vien…”) in Act Four. As both of these passages are of limited duration, such deletions were difficult to understand.

Boito’s tricky score alternating between arch lyricism in the chromatic “Ave Signor” redemption theme and raucous hurly-burly of the Pasqua and Notte del Sabba scenes were well managed although some of the ppp markings for chorus were noticeably louder than indicated.

The streghe and stregoni in the Brocken mountains were pungent in their various “Su su’s” but “Ci prostriamo a Mefistofele, al nostro Re” is marked ppp, not mf. The complex polyphony in the “Oriam, oriam” concertante section in the Prologue with its oratorio-like sonorites and emphatic crescendo marcato triplet accompaniment had real power without losing musicality and the top B natural for sopranos was choral singing at its finest. The “Juhé” chorus and Ridda e Fuga infernale were wild and orgiastic whilst retaining rhythm and raffinatezza.

The celestial trumpets were suitably intimidating and the massive fff brass-heavy orchestral tuttis powerful enough to intimate an imminent Armageddon. The marcatissimo marziale opening of Act One had punch and precision with decibel-shattering fff volume with tolling bells.

The low strings introduction to the Notte del Sabba scene was suitably spooky and later woodwind poltergeists plangent and chirpy with some especially effective playing from first clarinet. The obbligato during the Morte di Margherita scene was excellent. First flute also made a valuable contribution to “Ecco il mondo” and the Elena/Pantalis duet.

Strings were wistfully seductive in the andante amoroso introduction to Act Four and the final 5 bar sustained E-major tonality on “Ave” was sung and played “con tutta forza” as required and brought the opera to a tremendous conclusion.

Like the sins of Faust and Margherita, Àlex Ollé’s directional deviations were immediately forgiven – but not entirely forgotten.