Opéra-Comique Paris 2024-25 Review: Les Fêtes d’Hébé

Robert Carsen’s Production Reflects on Baroque’s Beauty & Highlights Lea Desandre’s Performance Alongside Stellar Cast

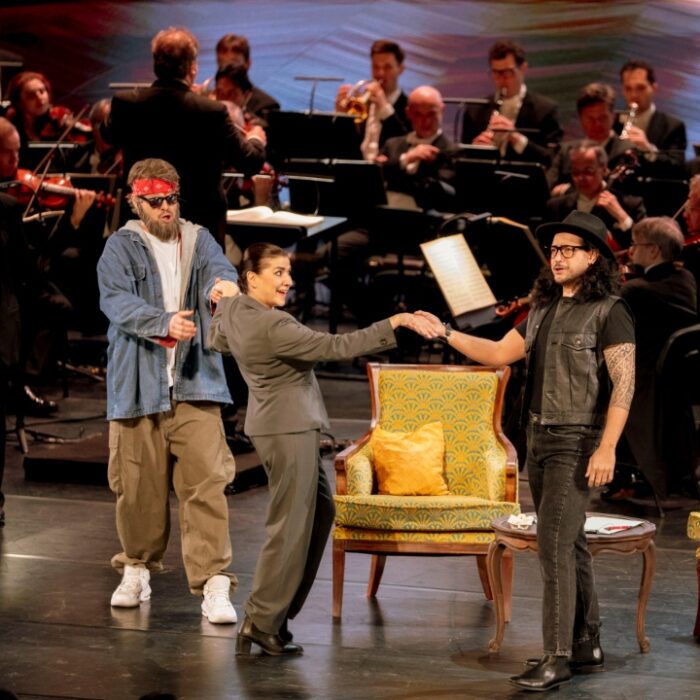

By João Marcos Copertino(Photo: Vincent Pontet)

If I were to rank the weakest opera libretti of all time, Jean-Philippe Rameau and Antoine-César Gautier de Montdorge’s “Les Fêtes d’Hébé ou Les Talents Lyriques” would certainly be in the top tier. Nevertheless, the opera-ballet possesses an allegorical charm that transcends the quality of its text—and it is a charm that is not solely musical. After the prologue, it’s hard not to feel enthralled by Rameau’s melodies and the vernacular quality of Montdorge’s text—as if we were invited to embrace the opera’s silliness and recognize that beauty can be found everywhere.

Opéra-Comique’s production of “Les Fêtes d’Hébé” is a compelling study of how pastiche and frivolity can still be deeply entertaining.

Production Details

For those unfamiliar with his work, it is typical of Robert Carsen to incorporate elements of pop culture into his operatic stagings—often drawing from unexpected or even questionable sources. Wisely, these pop culture references tend to amplify the political reflections within his productions rather than undermine them. His Meghanxit “Ariodante” and Giorgia Meloni-inspired “La Clemenza di Tito” offer a level of political nuance that, to me, feels more refined than much of what I’ve read in The Times or Le Monde in recent years.

Carsen’s “Hébé” hints at politics too. In place of the Olympus of the Greek gods, the prologue is set at an elegant soirée in the Elysée Palace, where the unfortunate Hébé spills wine on Brigitte Macron’s immaculate white dress. However, Carsen’s focus isn’t French politics. Instead, his staging reflects on how Paris—and France itself—can be both breathtakingly beautiful and unabashedly kitsch. Greek mythology merges with the modern mythology of Paris in what might be described as an elaborate Barthesian exercise.

In the post-Olympic Paris of the near future, we meet Sappho, Iphise, and Églé near the Seine on a summer day. The armies of the battlefield blend with the French soccer team, and in the end, Hébé takes us on a boat tour on the Seine, culminating in a view of the Eiffel Tower resplendent with sparkling lights. It could have been unbearably cheesy, but still— isn’t Paris that beautiful?

To recreate Paris on stage, without the budget of a Hausmannian restoration, Carsen employs a sophisticated system of projections that make the scenery surprisingly believable. His intentionally slightly off-key sets underscore the city’s artificiality, resulting in a production that is far more enjoyable than I anticipated. Given Opéra-Comique’s tendency to make all their productions look somewhat uniform, Carsen’s touch imbues this one with distinctive personality.

Perhaps the most harmonious pairing of the evening was Carsen’s staging with the musical direction of the beloved William Christie and Les Arts Florissants. While I have had mixed feelings about the ensemble in the past, their performances of Rameau are impossible to dislike. The Opéra-Comique’s voice-friendly acoustics further enhanced the bow articulations of the strings, highlighting the exceptional musical care.

Lea Desandre’s Illuminating Performance

The indisputable star of the evening was Lea Desandre, performing the three protagonist roles. Desandre’s 2024 season has been her strongest yet, with leading roles on Paris’s major stages—beginning with her “Médée” at the Palais Garnier in April. Her performance in “Hébé” confirms her promise as one of the great French interpreters of baroque music. However, while Desandre is already an exceptional artist, I feel she may be just one step shy of entering the true Olympus of classical singing.

Desandre possesses one of the most captivating voices of the decade, yet she is distinct from the archetypal French prima donna. While they—the French grandes dames singers—exude elegance and composure—think Isabelle Huppert or Catherine Deneuve—Desandre conveys a spontaneity and joyfulness that sets her apart. Though naturally a shy performer, she occasionally lets her perky, effervescent side shine. Her best moments—the ones that suggest she’s on her way to Valhalla—occur when she allows herself to abandon restraint and embrace her natural fluidity. This quality was on full display in “Hébé,” often in ways that transcended vocal artistry alone.

Desandre also dances—not professionally, but with an appeal that lies precisely in her earnest effort to embody music rather than to pursue technical perfection. Her artistry feels alive, evolving, and deeply personal. In Act two (Iphise’s act), her performance of “Tu chantais” in a wedding dress, addressing the waters of the Seine, was unforgettable. Her voice shone in all its glory, highlighting the innate charm of the French language as interpreted through Rameau’s genius.

Stellar Cast Highlights

The rest of the cast delivered equally strong performances. Emmanuelle de Negri brought charisma and impeccable diction to the small yet pivotal role of Hébé. Ana Vieira Leite, another rising star of Les Arts Florissants, impressed with her vocal beauty and her portrayal of Love as a frivolous social media influencer. Her usual angelic purity took on a sharper edge here, giving the character comic undertones that suited the production perfectly.

Marc Mauillon was outstanding, demonstrating a profound understanding of Rameau’s vocal style. His smooth vocal delivery and distinctive tone—a tenor with baritone undertones—allowed him even to approximate the haute-contre range when necessary. His portrayal of Mercure was charming, vulnerable, and witty. Renato Dolcini embraced the unapologetically masculine role of Tyrtée with ease, skillfully navigating the character’s contradictions.

In an opera-ballet, the choreography is as critical as the music. Nicolas Paul’s choreography, however, fell short. Capturing the tone of Rameau’s ballets is notoriously difficult. While the ballet company that originated this style resides only blocks away from Opéra-Comique, the seventeenth-century grace and movement they embody are no longer in fashion. Paul and Carsen attempted to modernize the dances with elements of street-dancing and sports, but the results were uneven. The soccer match mimicry lacked fluidity, and the third act party scenes, intended to evoke Seine-side revelry, felt less engaging than the teenage gatherings they sought to emulate.

It was a very Parisian night. Fanny Ardant with her hands covered in rings shone from the corbeille, and the public that usually avoids Trocadero felt sentimental paying the Eiffel Tower a visit. This “Hébé” is, by any measure, something extraordinary: a fresh window for the best of what the French school of baroque has to offer and a welcome reflection on our capacities to enjoy beauty.