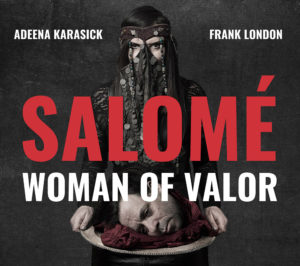

Off the Beaten Track: Setting the Salome Record Straight With London/Karasick’s ‘Salomé: Woman of Valor’

By Chris RuelBuckle up because we’re not just going off the beaten track, we’re going musical off-roading extreme style with “Salomé: Woman of Valor,” poet and performer Adeena Karasick’s wildly creative seven-year endeavor with Grammy Award-winning composer and horn player Frank London.

The work premiered at Vancouver, Canada’s Chutzpah Festival in 2018. Now, two years later, a studio recording drops on October 13.

London and Karasick seek to set the Salome record straight by presenting the eponymous character in a new light, one that looks beyond established depictions of her as a Jewish temptress/Christian killer. The work realizes its goal but in a highly unconventional way—using spoken word and music to create a pallet of sound the likes of which are akin to some darker corners of experimental electronic music, the closest analog of which is Alan Wilder’s Recoil.

The liner notes touted “Salomé: Woman of Valor’s” world premiere as a “massive total art experience.” I’m sure it was. I can more readily attest to another descriptor found in the notes: the work “defies all categorization.”

Review Vancouver wrote of the work: “Karasick’s Salomé is a warrior princess. She is complex, something like Zenobia, but more seductive and with better proprioception skills.” The words “complex” and “seductive” are entirely apt. “Salomé: Woman of Valor” is sexy — overtly so — but its sultriness results from how Karasick’s text and London’s composition mix and mingle their respective sounds to produce a heavy dose of sensuality.

Karasick’s spoken-word performance sizzles your ears with the breathy heat of her voice. It’s one thing to sit and read the text as the poetry it is, but poetry isn’t meant to be read but heard. Karasick’s delivery is hypnotic and erotic as waves of text roll and break, sometimes starting as whispers before sliding into chant-like passages that culminate in a libidinous frenzy. Throw in London’s velvety horn and imaginative mélange of styles from jazz to Middle Eastern to electronic darkwave, and you get an intense aural experience.

Will the Real Salome Please Stand?

London and Karasick’s thorough analysis of Salome lore pushes back against the femme fatale representations put forth by Richard Strauss, writers Oscar Wilde and Gustave Flaubert, and visual artists Gustav Klimt and Gustave Moreau. This who’s who of the arts (and Gustaves) perpetuated a profoundly ahistorical account as they wrote, composed, and depicted the princess in a very unflattering light. While the myths surrounding Salome are tantalizing fodder for creative minds, heavy strains of anti-Semitism run through the traditional narrative.

The Jewish historian, Flavius Josephus, mentions Herod II’s step-daughter Salome in Book XVII, Chapter 5,4 of “Antiquities of the Jews.” Josephus relates Salome’s marital life and the children she bore—that’s it; there’s no report of the infamous “Dance of the Seven Veils” and her subsequent request to have John the Baptist’s head on a silver platter.

The connection between the prophet and the princess arose out of the New Testament Gospels of Matthew and Mark (Chapter 14 and 6, respectively). Yet, in both Biblical accounts, Salome is unnamed. Sts Mark and Matthew refer to “the daughter of Herodias,” and “the girl.”

Was “the girl” Salome, or was the historical Salome a stand-in who served as a warning against the dangers posed to Christians by female sexuality?

Did early Christians use her as the poster child of the vicious anti-Semitic trope depicting the Jewish people as Christian killers?

It seems so based on Josephus’ exhaustive recounting of the tumultuous politics and personalities of ancient Palestine. The level of detail found in Josephus’ body of work makes it difficult to believe the historian would skip naming Salome as the murderer of John the Baptist.

Spoken-Word Opera?

Spoken word accompanied by music isn’t opera, but the manner in which London and Karasick structured the work elicited comparisons to the art form by critics.

The observation isn’t as far-fetched as it might seem.

The sections in which Karasick performs unaccompanied are not unlike recitativo. When backed by the full complement of instrumentalists, Karasick launches into aria-like numbers. London wrote interludes, which in the live production were dances, thus providing the ballet element. The pieces are all there — minus the singing, which for many would kick “Salomé: Woman of Valor” out of the genre. Fair enough; I won’t disagree.

However, since London and Karasick did a significant amount of research on the historical Salome, the work is worth an opera fan’s time as it places Strauss’ “Salomé” in context as historical fiction, not fact, and it enlarges our toolbox for understanding operatic work in a cross-disciplinary way.

‘Neo-Beat’ Poetics: Karasick and Kerouac

Karasick’s verse is reminiscent of that of the Beat poet, Jack Kerouac. She weaves words into tapestries of alliteration, creating a musicality that relies on how the phrases are spoken as much as the words themselves. I’d label the text “neo-Beat” — a cousin of Ginsberg, Kerouac, Ferlinghetti, and Burroughs. Spiritually, Kerouac blended Catholic tradition with Eastern thought while Karasick works within the realm of Jewish mysticism.

In a 2018 interview with the Jewish Independent, Karasick had this to say about the text: “I’m able to weave together the multiple styles of writing that I’ve experimented with over the years — sound poetry, homophonic translations, post-language conceptualism, kabbalistic and feminist revisionist practices, all syntactically playful, polyphonic, ironic and rhythmically complex — a fusion of my esthetic passions and expertise; opening a space of female empowerment.”

To sum the statement: be prepared for some wild text that’s a challenge to decode. But that’s so much of what makes the work so intriguing. It needs a cipher, but since it has none, Karasick and London encourage the free-play of the imagination.

London, who is a member of the Klezmatics and the Hasidic New Wave, “Salomé: Woman of Valor” drove him in a new direction as he worked to assemble a breathtaking range of music into a unified whole that complemented Karasick’s text. Punk, jazz, electronica, klezmer, and New Wave all have a seat at London’s musical table. In 2018, London, spoke of the music with The Georgia Straight, Vancouver’s urban news weekly, saying, “People know me from klezmer, but really avant-garde jazz is my home turf, and also different Middle Eastern musics and Indian musics and Arabic musics are all things I’ve studied. So what I really tried to do with the music is that I’ve taken all these elements and created kind of a dreamy world that is a mix of intellectualism and popular culture.”

Should I or Shouldn’t I?

“Salomé: Woman of Valor” is worth a listen. It’s not opera, but opera-esque and it provides an intriguing journey into the imaginative possibilities of the human voice, poetry, and music — all characteristics of the art form. Karasick’s knack for knocking words together and navigating the twisting, turning, and slithering onomatopoeia she wrote is captivating.

Tracks of note include the opening number, “Come,” “Gardens of Eros,” “Song of Salome” (a nice play on the erotically charged Biblical book, “Song of Solomon), “Give Me Head,” and, of course, a tantalizing and thrilling “Dance of the Seven Veils” in which London pulls out all the stops.

Accompanying London is an eclectic gathering of instrumentalists. Deep Singh plays the tabla, dhol, various percussion, and brings along his programming skills. Shai Bachar is on keyboards, electronics, and programming. On tracks 12 (Dance of Seven Veils) and 13 (Give Me Head), additional vocals are provided by Manu Narayan and Tony Torn.

I recommend using headphones for an immersive experience. Find a comfy chair, close your eyes, and let your imagination run wild with Karasick’s torrent of words and into the sensual mind of “Salomé: Woman of Valor.”