Monteverdi Festival Cremona 2024: L’Orfeo

Olivier Fredj’s Failure To Fully Realise His Insightful Reading Is Not Fatal

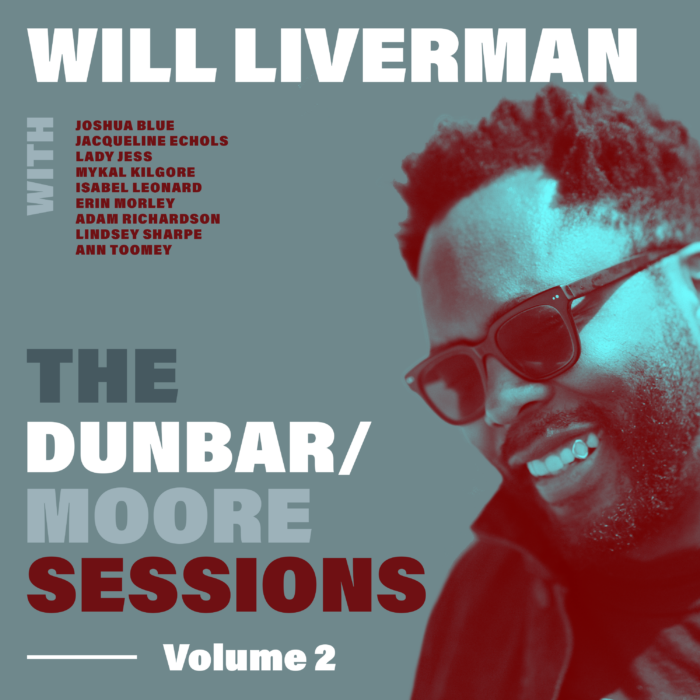

By Alan Neilson(Photo: Studio B12)

The advertising poster for the Cremona Monteverdi Festival’s production of “L’Orfeo” included the picture “Happy Hours” by Jean Lecointre. It depicts a woman with continuous streams of tears pouring from her eyes into a glass of wine, or does it? Could it be the reverse situation? Maybe the streams are moving in the opposite direction from the glass into the eyes. Both appear possible.

Ultimately, however, it is a matter of perception, and if one interpretation is accepted, then automatically the other can no longer be possible.

A Fascinating Reading that Did Not Translate into Practice

It was an image that succinctly summed up the director, Olivier Fredj’s approach, who wanted to open up a new perspective in presenting the work, one that takes into account the modern mindset, informed by the philosophical, societal, psychological and scientific developments that have taken place since its premiere over 400 years ago. In his program notes, Fredj made references to a number of factors that influenced his reading, including the paradox of Schrödinger’s cat, which seems particularly appropriate to the situation in which Orfeo finds himself. There were also intriguing references to the influences of quantum physics on how we perceive reality, presumably referring to the fact that the mere gaze of the viewer can change reality and that particles can simultaneously appear in two different physical locations, thereby bringing into question the nature of time as well as the relationship between cause and effect.

Unfortunately, what on paper sounded like a fascinating interpretation failed to translate into a staged reality. Apart from occasional references to perception, such as through video projections of eyes in various contexts or Speranza carrying a mirror on her back to reflect the gaze of the viewer, there was little that was immediately discernible to support Fredj’s reading. It was a real pity, as his ideas certainly had potential.

This was not to suggest that the staging in itself was not successful. In fact, it was a taut presentation that clearly captured the drama, albeit one with an inconsistent aesthetic. Thomas Lauret’s simple scenic designs consisted of little more than empty spaces with moving wings and arches that were used to expand or reduce their size. There was little in the way of props, and the coloring was dominated by dark hues, normally black. The stage, however, was brought to life by static images and videos, created by Jean Lecointre and Julien Meyer, projected onto the back of the stage, containing a variety of, often surreal, images, the meaning or relevance of which was not always clear. Camilla Masellis and Frédéric Linarès’s costume designs appeared to be a random assortment, ranging from the shepherds’ black tunics patterned with white-lined illustrations of faces, musical instruments or flowers to present-day clothing for Orfeo and others, while some were costumed in clothing from the 18th century or earlier. There was no consistent pattern; maybe it was a reference to quantum physics and the simultaneous positioning of matter across time.

While it was a staging that fell easily on the eye and allowed the drama to unfold almost unhindered, if one, of course, were not distracted by its opaque visual references, there was a degree of monotony about it; the pastoral scenes were dark and uninviting with little color or explicit references to rural idylls, greenery and vegetation. The most successful act was set in Hades, in which the dark, empty stage was covered in a red glow, its floor strewn with an unpleasant-looking jumble of material in which Orfeo scrambled around, set against dark video images.

Corti Leads a Strong Musical Presentation

Leading the Pomo d’Oro ensemble from the harpsichord, Francesco Corti elicited a sensitive, elegant reading with plenty of space for the music to breathe that allowed the score’s detail and its rich harmonic textures to emerge. It was also a beautifully balanced performance that allowed the singers to express themselves.

The role of Orfeo was played by baritone Marco Saccardin, who in 2023 won first prize in the Cavalli Monteverdi Competition. He is a singer with a fine voice, possessing both beauty and agility, which he used intelligently to mould the vocal line to develop characterization. He successfully burrowed deeply into the heart of Orfeo’s emotions to the extent that you could feel the full force of his passion for Eurydice, and the pain he experienced at her death was seared into his voice. Yet, his performance felt at odds with the musical production as a whole. Compared to the refined and sensitive approach of Pomo D’oro and the other singers, his emotional response came across as too strong, too demonstrative, and, at times, even appeared disconnected from the sensitivity and delicate tapestry being woven by the other musicians.

This was certainly not the case for soprano Jin Jiayu, whose performance in the roles of Eurydice and La Musica was sensitively aligned to the guiding musical aesthetic. Her singing was refined and delicate, and she exhibited a pleasing degree of controlled agility, which she displayed through her subtle inflections and gentle ornamentation of the vocal line. It is also a voice that was nicely suited to the musical textures of the orchestra, and together they successfully captured the beauty and delicacy of Monteverdi’s music.

Contralto Margherita Sala produced a vocally controlled yet expressive performance as the Messaggiera, in which she perfectly conveyed the sad and painful news of Eurydice’s death without any unnecessary histrionics. Her ability to fashion meaning through her use of dynamic and colorful inflections and emotional emphases was indeed impressive.

Soprano Paola Valentina Molinari convinced with a tidy performance as Proserpina, showing off her pleasing timbre and neatly crafted, if not overly ambitious, embellishments.

Her husband, Plutone, was given a suitably authoritative portrayal by bass Rocco Lia, and together they created a regal couple. He possesses a well-rounded, full-sounding voice, which he used sensitively to caress the words in what was a sympathetic reading.

Bass Alessandro Ravasio created a strong portrait of the ferryman, Caronte. His attractive, dark tonal quality and careful phrasing captured the gravity of his role.

The young baritone Giacomo Nanni engaged enthusiastically with his role as Apollo, displaying ambition and quality. His attempts to furnish the line with complex embellishments were most welcome, if not always perfectly executed, and added to the fullness of his presentation. He also successfully sang the roles of the fourth shepherd and the third spirit.

Mezzo-soprano Laura Orueta produced a confident, well-sung performance as Speranza, in which her light ornamentations and sensitivity to the text impressed.

The rest of the cast, including soprano Emilia Bertolini as Ninfa and tenors Roberto Rilievi and Matteo Straffi, along with countertenor Sandro Rossi as the shepherds, engaged enthusiastically, producing solid performances.

The chorus of the Monteverdi Festival, under the direction of Diego Maccagnola, gave a lively and emotional performance, capturing the shepherd’s joy at the couple’s happy marriage and their sorrow felt at Eurydice’s death. They also convinced in their role as the infernal spirits. Their singing ensured that the text was always clearly rendered.

Musically, this was a strong production, and although the staging proved to be overly ambitious by failing to live up to the expectations generated by Fredj’s program notes, it was by no means unappealing.